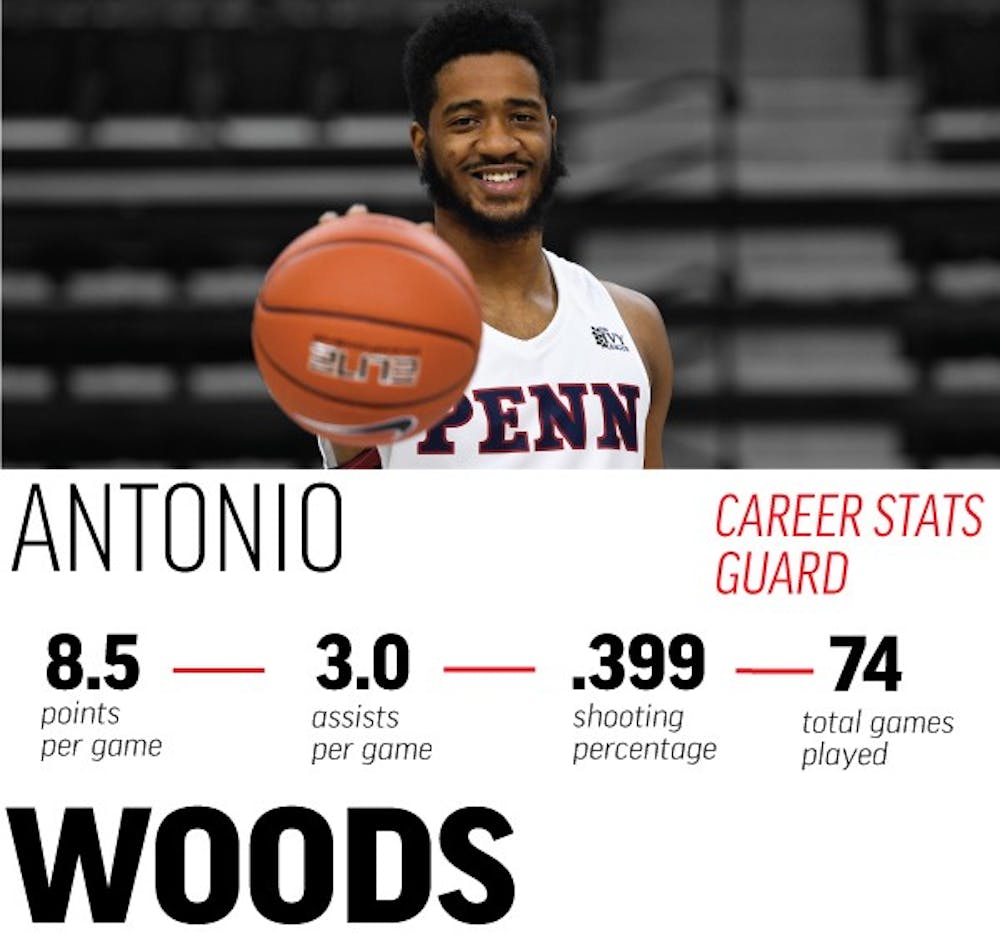

Less than two years after returning from a year-long academic suspension, Penn basketball senior Antonio Woods was named a team captain for this season.

Credit: Chase SuttonIt was March 22, 2012 — Antonio Woods was a sophomore in high school. His Cincinnati school, Summit Country Day, had just advanced to the Ohio Division III State Championship basketball game by beating Bedford St. Peter 49-41 in Ohio State’s Value City Arena. But all was not well for Woods and his team, even as they moved within one win of the school’s first-ever state championship.

No one knew exactly how bad it was at the time — all Woods knew was the sharp pain he felt every time he tried to run — but later, it would be discovered that a fall he took in the final minutes of the semifinals resulted in a torn medial collateral ligament (MCL), a knee ligament injury that typically takes several weeks to heal. The championship game was only two days away.

“We told Antonio and his mom that he was just not going to be able to play,” said Woods’ high school coach Michael Bradley, who played at Villanova before going on to play professionally in the NBA and Europe. “It was just too much of an injury risk.”

Woods tried to give it a go anyway. He spent all of the team’s day off before the championship icing his knee, but the reality sank in hard when he wasn’t even able to jog on the morning of the game.

“I remember going to [my mom] and I was just like crying, crying my eyes out,” Woods said. “I wanted it so bad and I just wanted to be a part of it. When I couldn’t have it, it killed me on the inside.”

As tip-off approached, Woods dressed in his uniform anyway — he said he told his trainer that he wanted to try to give it another go. When he walked out the tunnel to join his teammates warming up, his trainer stopped him.

“She comes up with a wide array of pills. Like her hand was filled with a lot of pills,” Woods said. “She was like ‘take these’. I’m like ‘take all of them?’. She’s like, ‘yes, take all of them.’

“So I took all of them. To this day, I have no idea what they were.”

The pills worked — or at least they worked enough. Woods limped his way to eight points in 20 minutes off the bench, and Summit defeated Portsmouth 53-37. He did not even learn the true extent of the injury until he got an MRI the day after the championship.

“I was really shocked to even think he was going to gamble and play,” Bradley said. “I don’t think it was just for himself. I think he wanted to be a part of the team.”

After spending much of the spring of 2012 rehabbing his torn MCL, he returned in his junior year to lead Summit to yet another athletic achievement — this time as the quarterback of the school’s football team.

With Woods under center, Summit finished the regular season undefeated and won the Miami Valley Conference Championship for the school’s first time since 2008. Woods was named the MVC’s Offensive Player of the Year.

While some coaches might have frowned upon Woods splitting his time between different sports, — he lettered in both football and basketball all four years of high school — Woods’ coaches encouraged it.

“His football coach and I had a great relationship,” Bradley said. “We wanted him to play on both sports as long as he wanted.”

Woods wanted to play both so much, in fact, that he spurned multiple Big Ten football scholarship offers to try to play both at Penn.

“At the time I knew I wanted to play football and basketball, that was what my heart really wanted to do, and that was kind of what I based my recruiting process off — like where could I play both sports,” Woods said.

When Woods committed to Penn, his plan was to redshirt his freshman football season while he focused on basketball and academics, and then play on both teams as a sophomore. But when Penn’s basketball and football programs both made coaching changes during his freshman year, Woods decided to focus only on basketball.

“I didn’t want coach Donahue coming in and thinking I’m not committed to the basketball team,” he said.

Woods proved his commitment to the team then — and he would again a few months later when his future with the Red and Blue was put in serious doubt.

. . .

Midway through his sophomore year, Woods was academically suspended for two semesters, starting with the spring of 2016. The suspension left Woods feeling “helpless” and like he had “nowhere to go”, according to an open letter to his younger self he would write later.

Bradley was concerned about how Woods would be able to come back. He said he texted Woods after he learned about the suspension and didn’t hear back for a couple weeks.

“I think that was just part of the initial phase of possibly being embarrassed, or ‘I don’t know what all these guys are going to say back home,’’’ Bradley said.

Even during those first weeks of the suspension, though, Woods was beginning to put his plan for the year off in motion. Through Penn coach Steve Donahue, Woods quickly connected with Kenny Holdsman, the President and CEO of Philadelphia Youth Basketball, a nonprofit organization dedicated to empowering Philadelphia youth. Holdsman agreed to mentor and employ Woods at PYB. There, Woods would work with middle schoolers as a coach and academic tutor.

"He has an authentic caring about kids that they immediately pick up on and resonate to," Holdsman said. "It's hard to see him in a gym or in a classroom without eight or ten kids huddled around him."

Needing to support himself, Woods also found work at Temple University Hospital, where he'd spend his nights transporting patients and the deceased.

When Woods first told Bradley about his plan for the year over lunch, Bradley thought it sounded so challenging that he was “concerned if [Woods] was going to make it.”

But by the end of their lunch, Woods convinced Bradley that he could do it. And by the end of the year, he had.

“He made it look so easy,” Bradley said. “I mean he was logging long hours and sleeping very little and in not so great places, but he was determined to make up for his errors and mistakes, much like he has been his whole life.”

. . .

Woods re-enrolled at Penn and rejoined the team for practices in January of 2017, although it wouldn’t be until the start of the next season in November of 2017 that he’d play in a game again.

When Woods finally did get the chance to play again — 22 months after he had last appeared in a collegiate game — his opportunities were limited. In Penn’s season-opener against Fairfield last season, Woods started the game but failed to score in only eight minutes of action. His team didn’t fare much better, losing on the road 80-72.

At the time, it was fair to wonder whether Woods simply wasn’t in good enough shape to return to his prominent role in the rotation. In the team’s next game, however, Woods logged 41 minutes as the Quakers lost a heartbreaker in double-overtime to La Salle. A couple weeks later, he played even longer, 50 minutes, in a thrilling quadruple-overtime victory over Monmouth, scoring a career-high 23 points.

By the time Penn’s season ended in March against Kansas, a game in which Woods scored 10 points in 35 minutes, there was little doubt about what he could bring to the floor this upcoming season as a senior and captain.

“He’s physical, he’s smart defensively, he always knows where to be. He was good from day one and he’s just gotten better,” assistant coach Nat Graham said, the only member of Penn’s coaching staff who has been with the team since Woods’ freshman year in 2014. “Now he’s as strong and as physical a guard as you’ll find in the NCAA.”

“He’s definitely our best defender,” junior guard Ryan Betley said.

But perhaps Woods’ impact on the team will be felt even more strongly off the court, where he’s established himself as a “lead-by-example” type of leader. Alongside the team's more outgoing captains, Woods is considered to be more of an introvert — and neither Woods nor Donahue sees any reason for that to change.

“[Donahue] told me all leaders don’t have to be vocal,” Woods said. “He said just be myself — and that’s what I like about coach Donahue. You can still be a leader as long as you be yourself, like don’t change for anyone, just continue to be your best self.”

In the eyes of his coaches, being his best self has been more than enough throughout Woods’ career.

“You’re not supposed to have favorites as a coach, but he’s one of them for sure,” Bradley said.

“I just admire his perseverance," Donahue said. “To me he’s why you coach.”

For more about the upcoming season, check out the project page for the 2018-2019 Penn basketball preview.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate