While many Penn alumni believe that America is more sharply divided now than during the civil rights era, 1974 College graduate Gerald Early sees a similar strategy being used in both movements: the power of creating crisis.

“Back when I was growing up, people would talk about jobs, they’d talk about freedom, they talked about getting rid of Jim Crow, getting rid of segregation,” Early, who is the chair of the African and African American Studies Department at Washington University in St. Louis, said. “The talk about reparations isn’t new. It goes back to the 1960s and even earlier, so that isn't new.”

The 21st century’s Black Lives Matter movement inspires numerous comparisons to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. But some Penn alumni — who have marched on America's bloodiest streets and decades later, remain committed to seeking justice — are not convinced there can necessarily be a direct comparison.

The Daily Pennsylvanian contacted Penn alumni and current students to provide a walk-through of the civil rights movement on Penn’s campus in the 1960s to present day.

A burgeoning civil rights movement at Penn, led by “a bunch of guilty white kids”

In the early 1960s, Penn and other college campuses across the country were just beginning to tackle the issues of the day, namely of the Vietnam War and of the United States’ civil rights movement.

1968 College graduate Adam Daniel Corson-Finnerty, who is white, grew up in a military family and arrived at Penn thinking he would go work for the U.S. Department of State. By the time he graduated from Penn, Corson-Finnerty said he would never represent the U.S. because of the "war crimes" he believes the country committed on a vast scale in the Vietnam War.

He also found himself completely alarmed by the America he saw during the civil rights movement.

“I was completely traumatized in the sense that this is my country and here are my people, in this sense really meaning white people, beating the crap out of Black people who are also my people, in the sense that we’re all Americans,” Corson-Finnerty said of the 1965 Bloody Sunday beatings of marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. “I went to a regular high school where they taught you that America was the greatest country on earth and we never talked about racial oppression. I had no education that prepared me for what was happening.”

The Edmund Pettus Bridge, which became a turning point in the civil rights movement, was the site of the Bloody Sunday beatings where Alabama state troopers beat demonstrators during the first march for voting rights. The televised beatings mobilized public support for activists and for the voting rights campaign.

Shortly after Corson-Finnerty heard of the attacks, civil rights movement leader Dr. Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference — an organization established under King's leadership in 1957 to coordinate local protest groups throughout the South — issued a public call to participate in the Selma to Montgomery marches. Corson-Finnerty, with some of his church group, traveled down and peacefully marched through the streets of Montgomery.

“The streets were completely blind on both sides. The main street in Montgomery, Alabama with white people who are screaming and yelling and spitting and calling us [N-Word] lovers and every nasty name they could think of. They were just hateful, totally hateful,” Corson-Finnerty said. “Then we get to the end of the march, and Martin Luther King gave an address to this huge crowd and he talked about love.”

King was a prime example of a “Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside” with the ear of powerful people on the inside and connections to the rest of the population on the "outside" according to Early, who believes that King in many ways was an agitator. “He preached non-violence but he wanted white people to be violent in response to that, because he knew it created a crisis,” Early said.

When Corson-Finnerty returned to campus after participating in the marches, he joined Penn’s NAACP chapter, which he said consisted mainly of white students. Some of the chapter's inaugural objectives were: political and vocational education, desegregation of housing, halting of police brutality, and discouraging of industries such as the Tasty Cake Corporation allegedly engaging in "selective patronage" when hiring employees, The Daily Pennsylvanian reported in 1960. Tastykake, a Philadelphia-based bakery accused of denying Black people employment opportunities in the late 1950s, was the first company confronted with the Selective Patronage Movement which organized Philadelphia's Black churches to boycott businesses that refused to hire Black employees.

“It was puzzling to me that there would be the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and all this stuff, and yet on campus, the Black kids were basically very quiet. They didn't get involved. But on the other hand, they didn’t organize these things. It was a bunch of guilty white kids organizing them,” Corson-Finnerty said.

In 1964, Corson-Finnerty coordinated the NAACP chapter’s 'Project Mississippi' initiative in efforts to raise $10,000 for displaced sharecroppers who wanted to transform their Tent City in Mississippi to a community center. He was one of the 20 Penn students who ultimately helped to build the center. Eighteen students were white and 2 were Black, he said.

'Project Mississippi' coordinator Corson-Finnerty addressing a meeting to discuss fundraising ideas.

The initiative, which was partly funded by the men's and women's student government, caused a “ruckus” on campus, according to Corson-Finnerty, and was barely supported by Black students at the time as it was "primarily white people talking to other white people and raising money from white people."

"It was true that Black students at Penn were not real active when it came to the civil rights movement, when it first started,” Corson-Finnerty said. “And the fact that us white kids were getting all worked up about it, [Black students] were like okay, alright. I'm going to keep studying. I'm working on my degree here, you know, this stuff isn't new to me. I know about this stuff. Or they came from privileged backgrounds where they themselves had experienced very little racism and they didn't particularly want to stick their necks out."

In 1966, Finnerty wrote a DP editorial titled "Civil Rights Apathy" in which he explicitly questioned "Where are all the Negroes? It doesn't take too many Campus NAACP meetings or too many reporters asking about Negro participation in Project Mississippi to make one curious about the state of Civil Rights at Penn."

Inspired by the budding Black Power Movement, Black students at Penn began to organize their own student groups in the mid-1960s, and white students, like Corson-Finnerty, led new groups such as People Against Racism that served to combat racism and ignorance within the white student community.

“The overall environment at Penn, just as the overall environment in most of the United States, was pretty racist in 1962, 1963, and 1964. And pretty white, right-wing,” he said.

By 1966, the Society of Afro-American Students was created to confront white privilege and combat racial inequalities, as well as create a sense of support for the Black community on campus. Five years later, the organization changed its name to the Black Student League. And out of the ten ratified proposals achieved in the 1978 Franklin Building Sit-In, where BSL members led a four-day takeover of the building to call attention to minority interests, the United Minorities Council was formed to represent students of color at Penn.

The rise — and immediate downfall — of political activism after the late 1960s

Like Corson-Finnerty, 1970 College graduate Ira Harkavy, who is white, participated in a number of regional demonstrations focusing on ending the war in Vietnam and the struggle of reducing and eradicating racism. Harkavy served as Co-Chairman of the Community Involvement Council, which he said was the largest organization of students involved in community service and anti-racism activity, and was a leader in Penn’s longest and largest sit-in to date: the 1969 College sit-in.

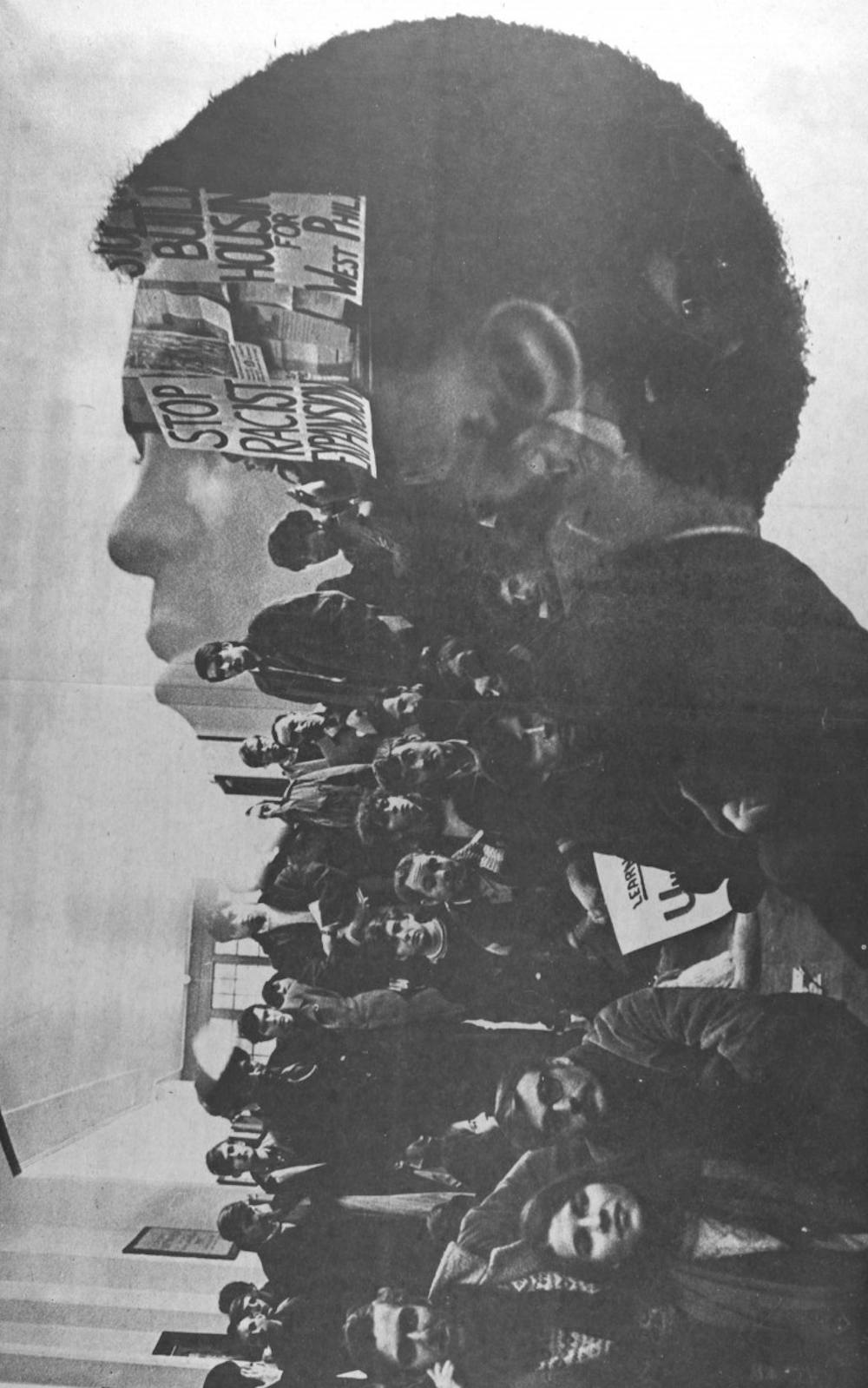

The cover of the September 1994 issue of 34th Street Magazine.

The 1969 sit-in primarily protested against Penn’s expansion into West Philadelphia that occurred as a result of the development of the University City Science Center, and the University’s treatment of the largely Black community that lived north and west of campus, which Harkavy said displaced thousands of community residents.

“Penn’s relationship at the time with the community was very problematic,” Harkavy said. He currently serves as the Associate Vice President and founding director of Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships.

“It’s true this University is committed to social change, but social change for whom and to what?” Harkavy asked a crowd of faculty members in 1969, accusing Penn of working for the “institutionalization” of West Philadelphia.

Ira Harkavy receives a standing ovation after addressing a crowd of nearly 2,000 students, faculty members, administrators, and Black community leaders after the six-day College Hall Sit-In.

Wary of attracting confrontational police presence on campus, Harkavy emphasized the six-day sit-in as a peaceful and democratic demonstration that would not engage in “ultra-radical activities.” Though all of the sit-in’s demands were not met, Harkavy said it achieved a newfound change of relationship between Penn and the West Philadelphia community — that community residents were no longer wholly left outside of conversations between students, faculty, and trustees. It was also when students “rebuffed their in loco parentis status and declared independence from trustees and administrators,” the DP reported in 1994.

In the years after the sit-in took place, however, student leaders witnessed an immediate decrease in on-campus activism as U.S. military involvement in the Vietnam War ended and the energy of the civil rights movement began to fade.

“Political activism died in 1970,” 1970 College for Women graduate and sit-in leader Lynne Mikuliak told the DP in 1994.

‘A fish out of water’: Racial divides on campus in the late 20th century

Liberal pressures from student-led protests across many American universities in the late 1960s led Penn to admit a significant number of Black students in 1970, Early said. He believes around 150 Black students, including himself, were admitted that year.

Many Black students “flunked out” and only a small percentage of Black students in his class graduated in four years, Early recounted. He said that his Black peers found it difficult to adjust to the University’s social and networking scene and also did not come academically well-prepared to be at a school like Penn.

“You’re going to a school for affluent white people and you know, the tune is that you shouldn’t be there. It’s for affluent white people so you know, you actually are like a fish out of water. And a lot of people meant well by having us there, but I think it was very difficult for many of the Black students,” Early said. He added that the generation of Black students in his class did not "hang around wealthy white people very much" and therefore missed out on the primary purpose of Penn: social networking.

Early said he thinks that most of the Black students and students of color he interacts with at Washington University, particularly those enrolled in the African and African American Studies Department that he chairs, likewise feel a sense of struggle and discomfort at the University — "a sense that you’re kinda climbing uphill a little bit.”

Was the “struggle” worth it for Early?

“I guess it was,” he said. “If I were 18 today and looking at college, I almost certainly wouldn’t go to Penn. It would be way too expensive. It was way too expensive then. But, the other thing is that for many of us Black students at that time, you know, this was a door opening for many of us. Our families told us to go.”

Early, a native Philadelphian, additionally noted that students felt a strong presence of an oppressive police force in the city with the rise of newly appointed Philadelphia mayor Frank Rizzo in 1972, who he described as “sort of a dress rehearsal for Trump.” The rise of Rizzo arrived with simultaneous wrestling over political power between Black people and white ethnics, Early said, which helped propel the Black political movement in Philadelphia.

On Penn’s campus, Early noted that a similar racial divide was present.

“There is very little communication between the races on this campus. All too rare is there a meeting of spirits between Blacks and whites here. The Blacks have formed their own almost sub-society and the whites solidify into a superstructure,” Early wrote in his weekly DP column in 1974. During his time at Penn, Early was the only Black person and the only student of color writing for the DP.

Writing about BSL’s first banquet in 1974 in honor of all Black graduating seniors, he noted that while there was much dissension among Black students at Penn, there were nevertheless moments of complete solidarity and unity.

An excerpt from 1974 College graduate Gerald Early's weekly Opinion column, 'A Day in the Life,' published in an April 1974 issue of The Daily Pennsylvanian.

That same year, 1975 College graduate and former BSL chairman Craig Inge told Early that “Black students on this campus just aren’t interested. They aren’t interested in the fact that we’re losing all of our programs, that the University is trying to make us invisible, make us just an integrated part of a total impotent student body.”

1989 College graduate Melissa Moody, who served as the president of the BSL during her senior year, remembers the experience of being Black at Penn as being part of a connected community. She attributed much of the success of campus activism from her BSL tenure to a climax moment in the 1980s of lightning-rod Black leaders — citing artist and director Spike Lee and politician Jesse Jackson — as well as burgeoning economic opportunities for women.

“I had a philosophy that I believe was a little bit different than my predecessors. Because what I saw was that there was no representation for us as Black people in the systems and structures that existed in the University,” Moody said.

1989 College graduate Patricia Fowler noted that though Black students were supported by the University, citing the Black Student Union and ARCH building used to house cultural centers, she felt there was definitely a level of disparity in how student groups were funded.

1989 College graduate and Black Student League President Melissa Moody addressing approximately 275 students on College Green at a rally for racial awareness.

After pushing masses of Black people to run for Student Activities Council and the student government, Moody said she was shocked to find that Black students won positions in SAC and ended up with the majority voice in the student government. And when racial injustices occurred on campus, such as a noose being drawn or hung in Hill House as Moody described, masses of students would publicly rally.

In addition to protesting acts of racism, Fowler said students also took issue with the University’s investments in South Africa, which had an apartheid government at the time, as well as the continued “push and pull” dynamic between Penn and West Philadelphia residents — an ongoing issue at the center of debates still happening today.

Moody said that during her tenure, BSL had official standing and experienced a lot of support from the Penn community. She added that a council composed of different campus ethnic groups — such as the BSL, UMC, a Caribbean students council and others — would regularly meet with former Penn President Sheldon Hackney when the groups had certain requests and demands.

“We were able to articulate in that period of time, not just what we didn’t want to see, but what we did want to see,” Moody said. “So if we were not represented, now we were. If there was attention brought to what was going on, then it eased. At least during that time frame, I do believe that we were successful.”

Have relationships really improved between Penn and its Black students?

Today, the BSL is one of 30 constituents represented by UMOJA, which was formed in 1998 as an umbrella organization of Black organizations and administrative voice for Black students on campus. UMOJA is now one of Penn's minority coalition student groups, which are together known as the 6B.

Current UMC president and College senior Brooke Price said that one or two representatives from each of the 6B groups meet with Penn President Amy Gutmann once a semester and with the Vice Provost of University Life on a regular basis. UMOJA co-chair and College senior Derek Nuamah believes 6B constituents have adequate "face time" with Gutmann and Provost Wendell Pritchett, but said there seems to be a disconnect between what is being discussed at meetings and what is being followed through.

"The frustrating part of that is from the changes that we're seeing, we haven't seen much at all," Nuamah said.

Along with current leaders of the Asian Pacific Student Coalition and Latinx Coalition, Nuamah has had meetings with administration to discuss the 6B's decades-long demand to move out of the ARCH basement and have central and separate spaces on Locust Walk. After rejecting the University's offer to relocate to ARCH's upper floors earlier this year, Nuamah said that Penn’s new Vice Provost for University Life did not seem to recognize the group's demands to move out of ARCH in their initial meeting in August.

"We made it quite clear between all three of us that that was unacceptable and that we will not really be looking for any more meetings with administration if pretty much they'll say things as if, oh, we hear you and those types of things," Nuamah said. "But with the lack of action being taken, it’s almost as if it’s just not clicking or they actually are not listening or at the very least it’s not a priority."

Current BSL president and College senior Kristen Ukeomah said she personally does not have conversations with administration, and believes it is “ridiculous” that Gutmann and the administration rely on very few people to be the voice of hundreds of unique Black and minority students on campus.

Ukeomah, who also serves as an Undergraduate Assembly representative, said that BSL has accomplished strong community engagement and growth in the past two years after re-stimulating a period of lost momentum in 2016 and 2017, but emphasized that Penn must offer more support to its Black community — particularly with financial support and adequate mental health resources.

Three of Penn's cultural centers — Makuu, La Casa Latina, and PAACH — are housed in the basement of the ARCH building on Locust Walk.

Price called on Penn to further support students from minority communities, hire more diverse staff and diverse therapists at CAPS, and provide greater physical space for the cultural spaces currently located in the basement of Penn’s ARCH building.

“College is not just about learning, it's about having community and having a social life and feeling well — physically, mentally, and socially. And if mentally and socially you're not well, I don't see how you can be academically,” Ukeomah said. Expressing concern about Black students’ graduation rate, Ukeomah said she has seen a lot of Black students have to take years off from school, take more than four years to graduate from Penn, and has seen some students not graduate at all during her time at Penn.

The six-year graduation rate for all Penn undergraduates is 96%, while the rate is 94% for Penn undergraduates who are underrepresented minorities and 92% for recipients of Pell grants, according to the University’s ‘Facts’ page.

During her time as president of BSL, Moody prioritized increasing the attrition rate for students of color which she said was then around 30%.

“From my perspective, it’s not protesting for protesting's sake because in my mind, the strongest statement that Black people at an Ivy League institution can make would be 100% graduation and moving on to impact society, leave a legacy, all those kinds of things,” Moody said.

Leaders of the 6B minority coalition student groups see students’ awareness and efforts to be politically engaged, but also sense a feeling of fatigue particularly within the Black student body.

Ukeomah said she feels a level of “defeatedness” among the Black community today. Although the students care about many issues, she said they just don’t feel like they have the strength to fight because their attempts often feel futile. She also believes that there is not enough Penn student activism today, and that the on-campus protests are very white-led.

“I feel like the Black students back in the day, they really demanded a lot and they were really doing stuff. I wish we could do stuff but I feel like there are a lot of limitations. I think also the presence of Penn Police can be very scary to a lot of people. If we organize a protest, what happens?” Ukeomah said. “From what I heard about what Black people were doing in the 60s and 70s at Penn, it’s definitely different.”

On the other hand, Nuamah believes that Penn is a politically engaged campus. "Sit-ins and those types of protests" are not the only ways to show students' political engagement, he believes. Price likewise said she is encouraged by the strong level of activism she sees within the Penn student body, citing students’ participation in the protests against racial injustice this summer.

On June 3, protesters sat in silence to honor the lives lost in racial injustice towards Black people in front of Jon M. Huntsman Hall on Penn’s campus.

America’s (and Penn’s) unfinished work

While alumni are inspired by the predominantly peaceful movement and the advantages of current technology, some are cautious of its capability to inflict long-lasting change. Though significant change has occurred, they agree upon one thing: America still has a lot of work left unfinished.

Some of the issues that existed in the 60s are still alive, Harkavy said, but he believes there is a much wider sense of urgency now about the need to create profound change on issues of injustice and inequality — a sense among people of all different political stripes that is present beyond communities of just activists.

“There has not been a progression in activism from the 60s to today, there is an increase of activism now that is significant,” Harkavy said.

Corson-Finnerty likewise said that students today are much more aware of the concept of white privilege and the context of what discrimination means from the get-go. He added that college campuses are often the hotbed of activism and political radicalism.

“We tried to get people to talk about institutional racism, but it was like, ‘What are you talking about? I'm not racist so if I'm not racist then I've done my part,’” Corson-Finnerty said.

After the police killing of George Floyd sparked a global reawakening of the Black Lives Matter movement in late May, many Penn students marched in solidarity and spread anti-racist messages on social media. Students, faculty, and alumni began calling upon the University to cut its deep-rooted ties with the Philadelphia Police Department and pay Payments In Lieu of Taxes — voluntary cash payments by nonprofit institutions — to the city.

Moody and Fowler, however, believe the use of technology and social media now simply exposes similar acts of brutality that have been occurring for decades.

“All of these things are still happening. You know, in the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, people were still being brutalized by police officers who were bad. People were still being drugged and lynched. And people were still being shot and disproportionate crime was still happening. We had the war on drugs and we had the mass incarceration, but only the people that were really engaged there, they saw it,” Moody said. “But now when you have technology, everybody is a reporter, everybody's got a phone. So if anything goes down, they can always be seen. We didn't have that.”

The “crisis” situation created out of the Black Lives Matter movement today revolves around specific acts such as a police brutality case, Early said, which ultimately creates political pressure to get concessions from people in power. But he and Corson-Finnerty warned protesters to be wary of being “co-opted” by superficial changes, advertised slogans, and temporary cash donations made by powerful institutions in response to Black Lives Matter.

“America is very good at co-opting things,” Early said. “If you co-opt [the protests], you take away the steam of it and you can smooth out the radical-ness of it and everything and you can almost put it into the mainstream culture and it kind of becomes part of that. You have to watch out for that.”

Elite universities like Penn have long received criticism as being “ivory towers,” removed from the financial hardships of their communities and the country in general.

In 1989, Harkavy, then the director of the Penn Program for Public Service, said that “Penn cannot be an island of affluence in a sea of despair.”

After leading the Netter Center for more than 25 years now, Harkavy believes that Penn is much less of an “island” than it once was, but that there has been insufficient progress in reducing the degrees of inequality and poverty that still exist in the wider community. The issue applies to urban universities in general, he said.

Penn for PILOTs is the first collective organization spearheaded by Penn faculty and staff to demand the University to pay PILOTs.

Demands that Penn pay PILOTs to Philadelphia schools, which are facing especially dire financial losses this year due to the coronavirus pandemic, were sparked by Black Lives Matter but have been circulating for years. Instead of paying the taxes, Penn argues that it instead makes a more impactful contribution to the mostly Black and brown residents of West Philadelphia through its over-500 community engagement activities going on in 248 schools, work facilitated by centers such as the Netter Center and Civic House, and direct investments into various sectors of city development.

The alumni acknowledge Penn’s efforts. But Moody, Fowler, and Early stressed the need for Penn to still pay the taxes and engineer spaces that facilitate interaction between West Philadelphia residents and the Penn community.

“When I’m looking at Black people today and I’m looking at the poor, Black neighborhoods we have in St. Louis, these places look the same and they are the same as they were 40 years ago. And, well, people say the University has got this school or somebody has invested this and this, well why is it that it doesn’t seem that anything has changed? This is one of the reasons why people are out there, because nothing on the face of it seems to have changed. You know what they say, the definition of insanity is you keep hitting your head against the wall but expecting a different result,” Early said, calling for universities to think about different ways to spend their money and act less as a buffer against the neighborhoods they are located in.

Nonetheless, the graduates remain hopeful about the current movement.

“From now on, it can’t be business as usual and we don’t want to return to normal because normal was not good,” Harkavy said. “Normal was in many ways as we’ve seen, inhumane. Inhumane, and violent, and cruel. And so we have to assure that we move forward and universities in my judgment are among, if not the most crucial institutions to helping to create a good, fair, decent, just, inclusive, democratic society.”

Thousands of demonstrators raised their fists in solidarity for Black lives in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art on June 3, 2020.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate

Most Read

More Like This