The 1970s was marked by significant student activism on campus. From a push to invest in West Philadelphia to anti-war calls for the University to divest from the military, Penn students made it clear that activism was as much a part of their campus life as their education.

During this time, one of the most successful movements on campus was the fight against sexual violence. In honor of Sexual Assault Awareness Month in April, The Daily Pennsylvanian took a look back at the progression of the anti-sexual harassment and Take Back the Night movement on campus.

1973

Title IX — the federal law ensuring the equal treatment of male and female students — was enacted in 1972, and court cases interpreted it such that schools were also required to protect students from sexual harassment and sexual violence. In April of 1973, students and community members organized a four-day sit-in in College Hall to protest the administration’s response to a series of rapes on campus. Their list of demands included more security personnel, the installation of emergency phones, free self-defense courses, better sexual assault reporting, and a campus women’s center. Every demand was met.

1975

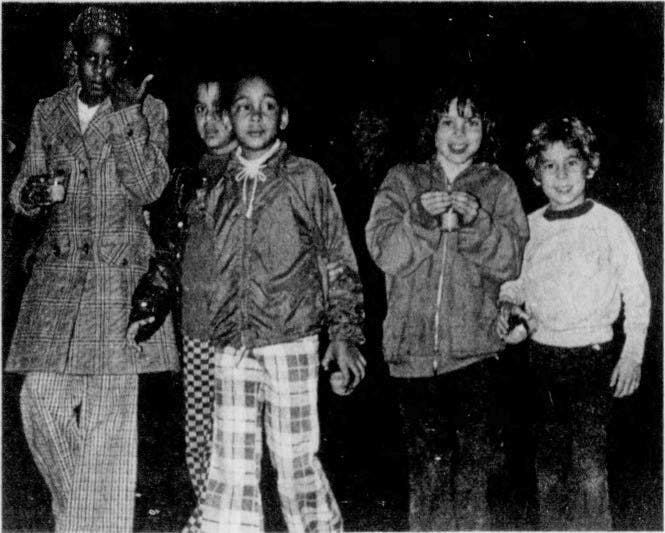

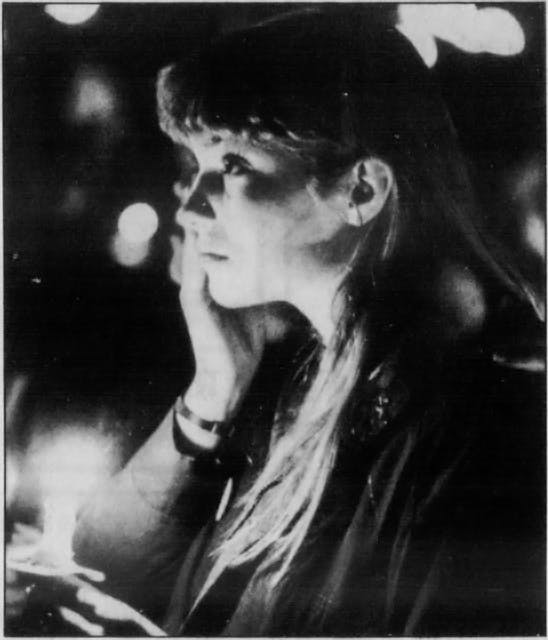

On Oct. 23, 1975, Penn lab technician and microbiologist Susan Alexander Speeth was stabbed to death. Three days later, over 250 Penn students, workers, and Philadelphia community members held a candle-lit procession in memory of the 37-year-old mother of three kids and to protest the increasing incidents of violence against women. Throughout the rally, attendees sang and chanted that they would “take back the night,” marking the beginning of an international movement against violence.

1990

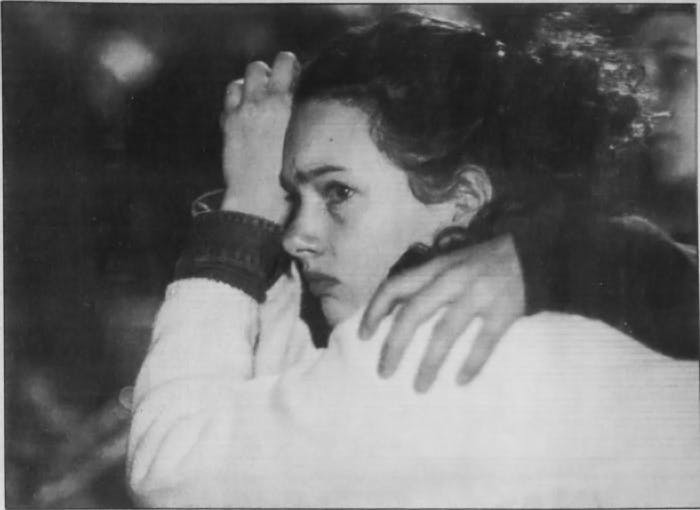

For the decade and a half following Speeth’s murder, there were no organized Take Back the Night rallies on campus. On March 26, 1990, over 400 students gathered on College Green for the first successful Take Back the Night event at Penn. Audience members shared their experiences with sexual harassment on campus, before participants marched to the University president’s house, shouting “stop rape now” and “take back Locust Walk” over the catcalls from several fraternity members.

1994

Four years later, Take Back the Night was held again on April 21, 1994. For the first time, the organizing groups publicized the event ahead of time, with sponsorship from the Penn Women’s Center. Throughout the week, women wore purple ribbons to signify their dedication to the Take Back the Night movement and tied white ribbons to a female symbol on Locust Walk to represent individual acts of assault.

However, some were dissatisfied with the fact that the event only catered to women.

“I’m not safe here at this school,” then-Penn graduate student Brian Linson said at the time. Linson, who filed a sexual harassment complaint with the Department of Education against the University, was expelled in 1993.

“This happens to women, but it also happens to men,” he said.

Elena DiLapi, a graduate from Penn’s School of Social Policy & Practice and Penn Women’s Center’s longest-serving director, said the rally’s emphasis was purposely limited.

“We chose to focus on women, not to exclude our brothers, but rather to underscore the pattern of violence,” she said.

1995

Attendance reached an all-time high at around 500 people on April 27, 1995. While female students and Penn affiliates marched down Walnut Street, the men in attendance were asked to remain behind to listen to a speech from 1995 College and Wharton graduate Zachary Liff, a member of Students Together Against Acquaintance Rape.

While some male students were offended that they were unwelcome during the procession, organizers defended the decision.

Nirva Kudyan, a 2003 College graduate and now vice president of the University’s National Organization for Women chapter, said male support was welcomed, but that Take Back the Night was about women.

“Take Back the Night has fundamentally been a way for women to reclaim the right to walk alone in safety,” she said.

That year, during the event’s Survivor Speak-out — the open-microphone portion of the rally where anyone can speak about sexual violence — a male student stepped up to publicly apologize for having raped a woman. Then, 1995 College graduate Felicity Paxton, the director of the Penn Women’s Center from 2008 to 2018 and now the associate dean for undergraduate studies at the Annenberg School for Communication, called that incident “a grotesque misuse of the event.”

“It’s inappropriate for a rapist to stand up and ask for time in front of a group of women survivors,” she said.

1997

Controversy peaked during the fourth annual Take Back the Night on April 3, 1997, after organizers discouraged men from participating and marching.

“This is the one bloody night of the year that we ask you, as men, to shut up and listen,” Paxton said. “You see [women] all over the place, and when you want our bodies on the cover of Sports Illustrated, they’re there. But I don’t think you really hear us.”

Responses from the Penn community were divided, with people condemning and supporting her statement.

1998-2003

While Take Back The Night continued annually in April throughout the rest of the decade, attendance began to decline. Policies regarding the open-microphone portion of the night and who would be allowed to participate also changed from year to year, sparking controversy each time.

2004-2006

2004 was the first year that Take Back the Night was completely student-planned and student-run. That year, participation was around 60 people. The next year, there was less than two dozen attendees. The lack of attendance was attributed to decreased membership in student advocacy organizations and a lack of promotion from sororities. In 2006, Take Back the Night did not take place at Penn.

2009

Take Back the Night returned in 2009, organized by the Abuse and Sexual Assault Prevention group in partnership with One in Four and other campus groups. Penn students and employees discussed how the event should be organized, as well as what role men would play in the effort.

2016-2019

Take Back the Night enters its modern form at Penn, with the event featuring a keynote speaker, rally, march, and survivor speak-out. The attendance grew year by year, with hundreds of Penn students, faculty, and community members participating. Although former Penn President Amy Gutmann sent letters and emails expressing her support annually, she faced criticism for her continued absence.

2022

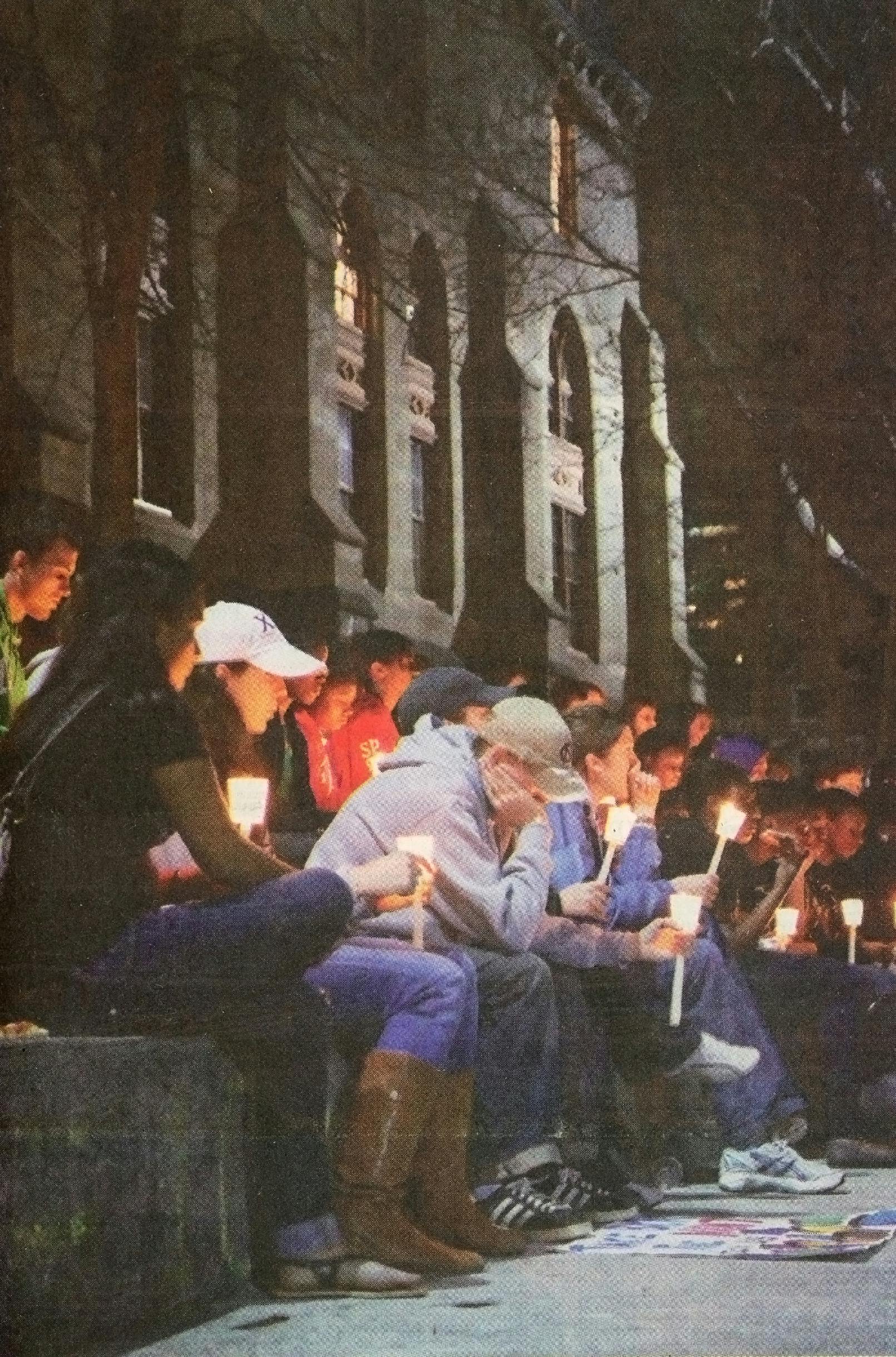

ASAP hosted Take Back the Night in person for the first time since the pandemic on April 7, 2022. A rally opened the event, which also featured performances from student performing arts groups. At the night’s vigil, no phones were allowed and confidential resource centers were present. Former Interim Penn President Wendell Pritchett was scheduled to provide brief remarks at the event but was unable to attend, according to ASAP leadership, who said they received an email from his office a few hours before the event.

2024

Take Back the Night featured a resource fair with organizations from Penn and Philadelphia for the first time on March 21, 2024. The change was implemented after a recent University survey found that 78% of Penn students do not know how to find help in the event of experiencing sexual abuse. At the event, then-Interim Penn President Larry Jameson spoke about the importance of educating people of their rights. He said the highest priority of the event was spreading awareness to prevent incidents of sexual abuse before they happen. The night ended with a candlelight vigil and stories from survivors of sexual abuse and domestic violence.

Take Back the Night takes place this year on April 3.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate

Most Read

2013 Wharton graduate Charlie Javice convicted of fraud, conspiracy in JPMorgan case

‘At least three’ Penn students had visas revoked, ISSS says

Penn announces $5 million gift for inaugural professorship in philanthropy

More Like This