Last September, Penn President Larry Jameson noted that Penn’s values draw upon “our Latin motto, Leges Sine Moribus Vanae, which is commonly translated into English as ‘Laws without morals are useless.’” He added, “These few words communicate very deeply.” He then helpfully explained what these few words communicate, “The motto urges us to do what is good and practical, and also what is right.”

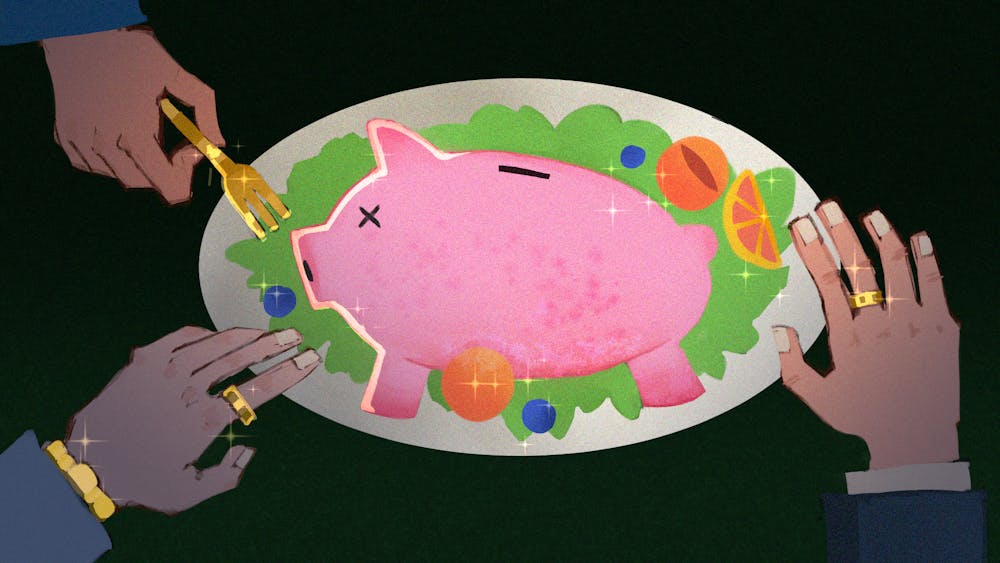

Unfortunately, words like “good” and “what is right” are opaque and confusing, which has led to disagreements that have created tension and disruption on Penn’s campus over the past 15 months. In order to resolve these issues, Penn has tirelessly worked with its most valuable community members to find common ground. By engaging the University’s donors in this way, everything has improved and everyone is now happy.

This empathetic approach has demonstrated Penn’s laudable commitment to the principle of collaboration. As Penn noted in its 2023 strategic framework, In Principle and Practice, “Penn’s principles are the essence of who we are.” These principles include being “anchored, interwoven, inventive, and engaged,” which are usefully vague and imprecise. Happily, the strategic framework also noted that “Penn seeks dialogue and collaboration across differences and divides.”

In this way, Penn sought to bridge divides with donors through dialogue in spite of salient differences like Penn’s desire for funds and their possession of funds. More recently, Jameson once again embraced the principle of collaboration after the Trump administration made clear that certain values the University had long promoted were, in fact, wrong and not good. Thankfully, In Principle and Practice is a “living framework,” which means it can be corrected.

In spite of these judicious actions, recent Trump administration funding cuts — including a targeted $175 million dollar funding pause on March 19 — will once again challenge Penn to find creative solutions. In the piece “Penn’s endowment, explained,” an easy-to-understand article that helpfully avoided complicated statements like “money is fungible” while explaining why our massive endowment could not solve Penn’s funding problems, the University’s in-house magazine Penn Today wrote, “Like a retiree, a university must strike a balance between short- and long-term needs when spending from investment assets.” Also like a retiree, Penn is not working and expects to survive for another 20 years before passing on a lot of mid-Atlantic real estate to its heirs.

In light of these challenges, the University should emulate its various board members instead of simply taking direction from them. How can Penn emulate these inspiring figures? By learning from their strategic practices. In particular, Penn should begin collaborating directly with wealthy nondemocratic regimes that torture people in order to redress its short-term budgetary problems.

For instance, chair of the University’s Wharton Board of Advisors, Marc Rowan, has built direct partnerships with different United Arab Emirates sovereign wealth funds, enriching a government that systematically tortures peaceful political dissidents. Partly as a result of this strategy, Apollo Global Management has not been forced to institute a hiring freeze and has not lost any National Institutes of Health funding.

Indeed, the University already has the in-house expertise needed to achieve closer working relationships with such a regime. According to Bloomberg, Wharton Board of Advisors member Kenneth Moelis recently completed a “long courtship” involving his bank and the UAE, leading to so much business that his firm “had to tear down walls at its Dubai headquarters to make room for its expansion drive.” Leveraging this strategy, Penn might consider building a similar relationship by flirtatiously highlighting its expertise in the “biopsychosocial aspects of pain and pain management,” which will help the UAE with its dissident containment strategies.

Now, some might worry that trustees like Arp Ercil, Brian Schwartz, Dhananjay Pai, and Michael Price have so effectively siloed their firms’ relationships with these regimes from their jobs overseeing Penn that it will be difficult to take advantage of their know-how. But as University Trustee Massi Khadjenouri stated in an interview with The Hedge Fund Journal, a journal about hedge funds, “We do not believe in silos. They create all sorts of problems, at the interpersonal and investment levels.”

Given the extraordinary challenges Penn now confronts, it should perhaps take this initiative even further. As In Principle and Practice stipulates, “Great universities are like great cities. They never press pause on their own reinvention.”

In troubling times, embracing reinvention requires moving beyond outdated ideas like satellite campuses in Abu Dhabi. Instead, Penn should simply become Abu Dhabi, which would have the attendant benefit of solving the problems posed by student protestors.

By becoming Abu Dhabi, Penn would also benefit from various policy changes. For instance, Penn could silo from all human contact any student who presented thought experiments like, “If you have a rainy day fund and there is a hurricane outside, should you use the rainy day fund even though a hurricane is meteorologically distinct from a rainy day?” Further, Penn would be able to torture union members, which would more clearly define the relationship between the University and its graduate workers, which graduate workers claim to want.

Now, some might argue that these practices would contravene Penn’s “core value” of free expression and inquiry. This is not true. Obviously, a graduate student being tortured would be free to express pain and to inquire about the implements being used.

Moving forward, these necessary changes will also set Penn up for a productive working relationship with the United States government as the U.S. torture statute considers its own retirement.

Admittedly, emulating the University's board members and trustees in this way may run contrary to our motto. This clearly indicates that our motto isn’t any good. Instead, I suggest that Penn adopt “Willing to collaborate.” Like the old motto, these few words sound nice. They also have the added benefit of being very vague, while still communicating deeply.

NICK FORETEK is an Ph.D. student in History. His email is nforetek@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate