What does being first-generation, low-income mean for college students? For me, the identification as “FGLI” is just like any other social identifier. It’s a testament to my educational journey, a mark of my family’s persistence, and a classification I wear with confidence. From my first weeks on campus, I was thrilled to connect with Penn’s FGLI community and the Penn Questbridge Scholars Network. Even though I found many that shared my excitement, the pride of being FGLI in a distinguished institution seemed confined to certain spaces. Peers that once so openly embraced the identity in one club avoided mentioning it entirely in another.

My initial assumption was that many students may feel the sense of shame that’s common in FGLI students all over the country and not just exclusive to Penn’s campus. Yet what I once perceived as a widespread embarrassment of the identity I now recognize to be a distortion of its purpose. The FGLI designation houses a wide umbrella of familial situations that are often defined differently depending on the club, organization, institution, etc. This ambiguity makes college students eager to take advantage of the title primarily when the status comes with worthy benefits.

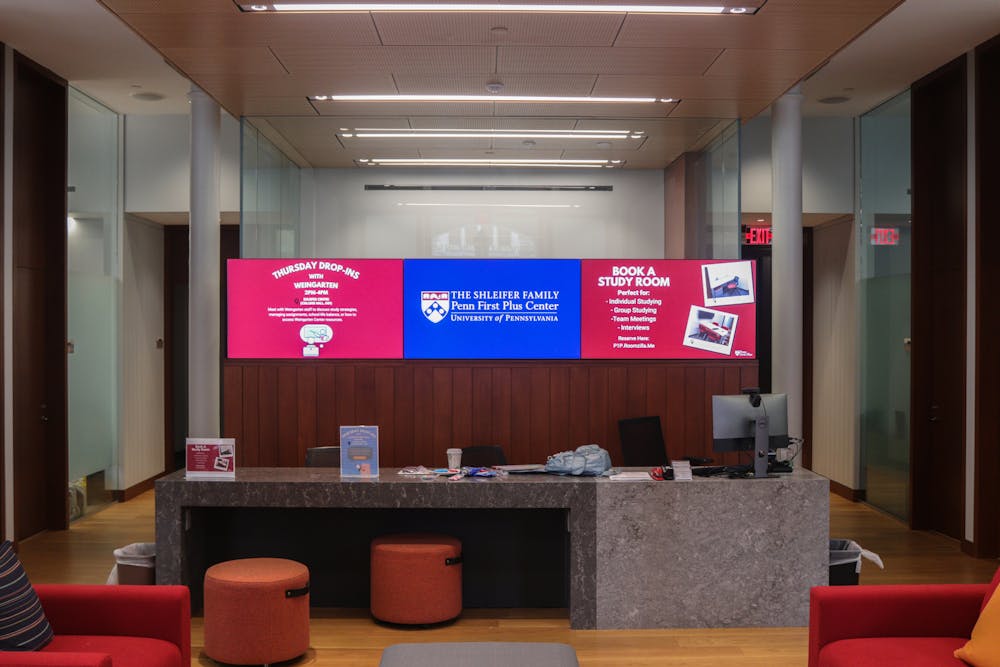

At Penn, the largest hub that serves first-generation and/or low-income students on campus is Penn First Plus. P1P’s definition of FGLI encompasses students who are “first in their families to pursue a four-year baccalaureate degree or come from modest financial circumstances.” It’s a definition that is widely accepted by Penn clubs and often used as a model for defining what FGLI means. This means that students whose parents attended college but undertook less traditional routes (i.e. associates degree, trade school) can still be considered FGLI. Penn First, another first-generation, low-income organization on campus, defines first-generation students as the first in their family to “pursue higher education at an elite institution.” What is deemed as “elite” is completely open to interpretation. For example, students who only consider top-20 colleges as “elite” but still have parents who attended distinguished institutions may consider themselves first-generation. After all, who can truly contest a word that carries such nuance?

“Low-income” is just as vague a terminology as first-generation. Highly Aided students are often most clearly identified as low-income, but there are plenty of other students who may still struggle financially but qualify for less aid. These individuals are stuck in a middle ground, lacking access to certain resources provided by the school yet still facing challenges that strain their college experiences. Others may have home situations that prevent them from receiving any support from family members. In that case, the assets reflected in their application don’t accurately mirror their current circumstances. Because of these inevitable scenarios, P1P acknowledges that the subjective nature of the term “limited income” prevents them from strictly defining or regulating the term in order to allow for students in these predicaments to make use of their resources. The one downside to such an approach is that students take advantage of its absence of regulations.

With so many loopholes in its definition, the FGLI community is composed of both students whose college experience is contingent on the resources provided by programs like P1P and the wealthier students who take advantage of the obscurity of the status. More than once I’ve stumbled upon a conversation where students admit to avoiding reporting minor property holdings abroad in order to appear more financially “needy” than they actually are. However, we must not forget that FGLI needs do extend outside of financial support. Getting acclimated to a college environment is already daunting, but not having additional support from family members who have experience with the demands of college is another disadvantage.

So where exactly do we draw the line between self-advocacy and policing?

No one wishes to create an environment where students feel pressured to justify their use of certain resources. Yet there exists significant discrepancies between those who need institutional support and those who simply game the system.

As universities like Penn struggle to balance accessibility with fairness, this gray area raises critical questions about student privilege and the ethics of resource distribution. Ultimately it is up to students to determine whether they genuinely need these resources. But ask yourself: Are you taking advantage of a system designed to support those with fewer opportunities than you?

If we want to truly level a playing field that has long been uneven, we must realize why these programs are put in place in the first place. The way the student body engages with FGLI resources is not just a reflection on us as individuals, but also on the integrity of the institution.

ALYMA KARBOWNIK is a College first year from Maplewood, N.J. studying international relations and environmental studies. Her email is alymak@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate