The bombshell that was anything but.

On Monday, Ivy League Executive Director Robin Harris emailed the conference’s athletes and coaches with an order from up high, the kind the conference has made plenty of in its 70-year history: The Ancient Eight will opt out of a pending House of Representatives settlement set to provide direct compensation to NCAA Division I athletes, preserving its existing model which opposes payment for athletic participation, better known as “pay for play.”

“[The Ivy League] will not change longstanding rules, including those that prohibit any form of compensation for participation in any intercollegiate athletics program,” Harris wrote in the email. “… [The league] will continue to not provide student-athletes with revenue sharing allocations, athletics scholarships, or direct NIL payments …”

The league’s decision is unique, as it will likely be the only D-I conference to abstain. It is significant, as it will hinder the conference’s ability to recruit and compete in the same arena as paying schools. But there is one thing the ruling is not: surprising.

As college athletics have turned upside down in recent years, the Ivy League has been content to watch the world go by, maintaining confidence in the viability of its founding principles. In that sense, the House decision is not a new development, but rather the latest in a long line of decisions the conference has made to tie its own hands.

While the House settlement has not yet received final approval, many D-I schools have already begun preparing for its ramifications. VCU, whom Penn played in men’s basketball this season, recently announced that it would opt in to the settlement and pay a total sum of roughly $5 million to its athletes starting next fall.

The Ivy League’s opposition to payment for participation is nothing new. The founding Ivy Group Agreement prohibits athletic scholarships, and while the conference has allowed its athletes to pursue “legitimate” name, image, and likeness opportunities in the years since the advent of the practice, it has shied away from NIL collectives and other forms of direct payment that dominate college sports’ upper crust.

It is worth noting that the Ivy League does not apply this standard to its team units. In many sports, specifically in basketball, smaller programs like the Ivies play in “money games,” where they travel to play a larger school and receive a lump sum in exchange. This season, Penn men’s basketball played at VCU and Penn State, Brown played at Kansas and Kentucky, and Yale played at Purdue and Minnesota. The Ivy League teams went 0-6 in those games, but the athletic departments were paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for them.

The conference argues that there is a difference between athlete and team, and that direct compensation would jeopardize its mission to prioritize academics over athletics. But these pursuits are not mutually exclusive. Several other elite academic universities — Stanford, Michigan, Vanderbilt, and others — have kept up with the modern age of college athletics without sacrificing their commitments to the classroom. But the Ivy League is its own club, convinced that it must unflinchingly abide by strictures written before the invention of the permanent marker.

The league’s officials are not the only ones with decision making power. In recent months, the conference has seen perhaps its largest exodus of star undergraduate talent in history, with stars from top-earning sports like football and men’s basketball transferring out of the league in droves. Last spring, four top men’s basketball players — Danny Wolf, Malik Mack, Tyler Perkins, and Chisom Okpara — left the Ivy League for bigger programs— programs that participate in the pay-for-play boom.

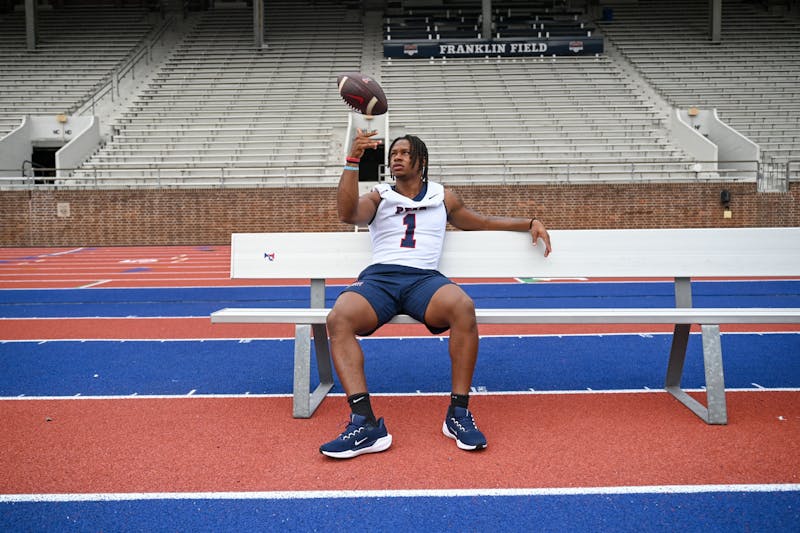

In the fall, a similar wave occurred with the conference’s football standouts, where leading rusher and Penn sophomore running back Malachi Hosley and leading receiver Cooper Barkate left for big-time programs. Jackson Proctor, quarterback of Ivy League champion Dartmouth, also transferred to an FBS school.

“When you see all these other schools looking out for their athletes, it sort of gets you thinking, ‘Oh, maybe the transfer portal would be best for me and my family,’” junior wide receiver Jared Richardson, the conference’s fifth-leading receiver, said in wake of the House settlement.

The House decision is consistent with the Ivy League we know, but it nonetheless compounds the league’s other self-imposed disadvantages. With no scholarships, no pay-for-play NIL, and no revenue sharing, the writing is on the wall for the league’s major sports to fall into obscurity, all in the name of protecting an amorphous academic mission.

Ivy League teams have a mission of their own: to win. But it is becoming increasingly clear that their schools do not share it.

WALKER CARNATHAN is a junior and former DP sports editor studying English and cinema and media studies from Harrisburg, Pa. All comments should be directed to dpsports@thedp.com.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate