On Nov. 5, American democracy hung in the balance as a “turbulent [presidential election] campaign near[ed] its finale.”

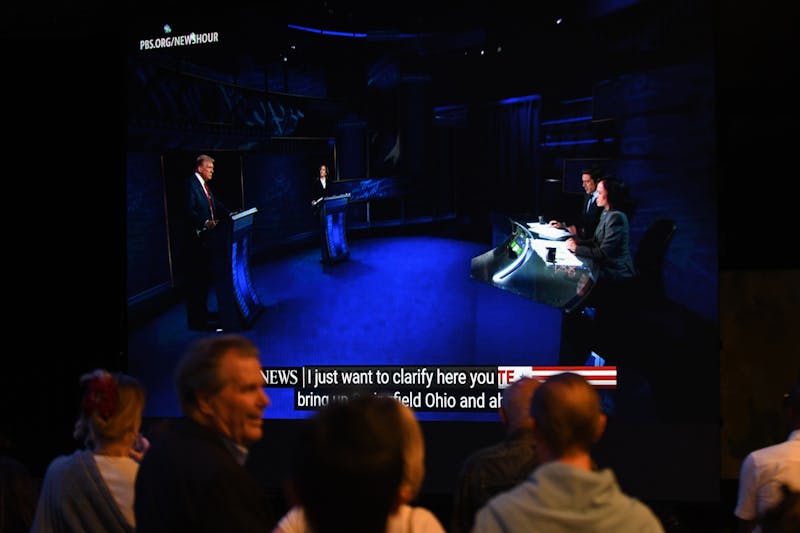

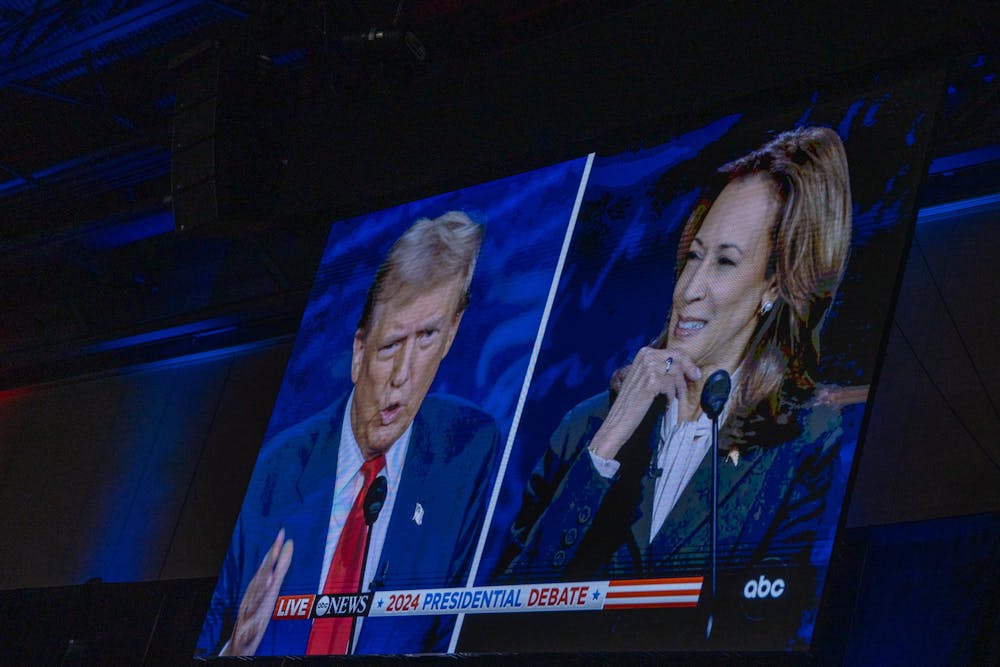

At least, this narrative is what many mainstream news broadcasters have chosen to headline as voting centers began to close. This election was certainly expected to be a toss-up, with Vice President Kamala Harris and former President, as well as 1968 Wharton graduate Donald Trump virtually tied in polls without a clear victor in sight.

With an escalation in the Israel-Palestine conflict — now involving Lebanon, Iran, and potentially other regional actors — American diplomatic efforts are under greater scrutiny this election season. Nuanced positions on the issue are portrayed as weak, as “both sides'-ing" problems with seemingly clear solutions. An opinion piece from the Jerusalem Post claims Harris is “appeasing Hamas” while many of Trump’s critics view his presidency as a route to actualizing “The Handmaid’s Tale.” And so, our options for this election were regimes tarnished by either fundamentalism or sex slavery. These hyperbolic soundbites are rooted in lived experiences (in this case, many activists compared Trump’s overturn of Roe v. Wade to the sexual exploitation of handmaids in Gilead). Yet, when real issues are irresponsibly politicized for easier engagement, voters bear the hostilities of a so-called political binary. Ironically, many of Harris’ economic positions were similar to Trump’s. Both candidates supported eliminating federal taxes on tips. They also didn’t plan to pursue a single-payer healthcare system. Since the 2016 presidential election, Trump has actually changed his stance on reproductive freedoms, answering “no” when asked if he would sign a national abortion ban. On the other side, Harris has never proposed specific gestational limits on abortion access. While firmly pro-choice, she has yet to actually comment on conservative fears of unrestricted abortion access at any stage of pregnancy, including "abortions after birth.”

I don’t claim to stand on the high ground of political objectivity, particularly because I have many incentives to prioritize personal, albeit trivial, interests. Part of my family hails from the Cauvery Delta in India — a small, fan-shaped area the size of Connecticut — where Harris shares ancestral ties. While I strongly oppose political decision-making on the basis of identity, I couldn’t help but revel in the buzz that coursed through Indian and Sri Lankan diaspora communities at the fleeting (and now short-lived) possibility of “one of us” reaching the highest office in the country — a country where Indian-born actress Merle Oberon crafted a false European identity to land roles in early Hollywood.

Much of my lived experiences, however, were shaped by the Pee Dee region of South Carolina, a reliably red part of the state known for its cotton farms, roadside Baptist churches, and Civil War-era Confederate monuments. I’m neither Christian nor a descendant of the Southern gentry. In the words of a left-leaning scholar, “the party of white America” has tainted the lives of myself and many other minority groups in conservative voting districts. However, we hardly faced an “either-or” political climate. As a testament to my point, in the 2024 South Carolina primary, Nikki Haley secured 40% of the vote. To put it more starkly, Haley, a woman born to immigrant parents, levied substantial resistance to Trump, who was endorsed by almost all of South Carolina’s Republican leadership.

I’m aware of challenges specific to any administration. I remember how Trump’s “Muslim ban” emboldened my racist middle school classmates, many of whom would mockingly cower under “bomb-safe” desks whenever a hijabi entered the room.

But in a representative democracy, there is always room to elicit change. The Republican Party, for instance, has swapped “anti-Muslim fearmongering” for a somewhat softer pitch as Arab and Muslim American voters grow disillusioned with the Biden-Harris administration’s support for Israel. In a Michigan rally, Trump — in spite of his earlier self-designation as a “protector” of Israel — portrayed Harris as a "warmonger" who will “invade the Middle East, get millions of Muslims killed, and start World War III.” Many community leaders remain haunted by Trump’s call for a “total and complete shutdown” on entry to the United States from several Muslim-majority countries. Nevertheless, they find the current administration to have “failed miserably in all aspects of humanity,” so much so that they now “look to a Trump presidency with hope and envisioning a time where peace flourishes, particularly in Lebanon and Palestine.”

Of course, elected officials act in self-interest and their altruistic gestures are usually political theatrics. But the fact that our leaders feel a need to respond to their constituents is a sign of democracy at work. The system, as imperfect as it may be, leaves the government answerable to the public. Regardless of your thoughts on the outcome this week, our ballots will always have future opportunities to push for change. If you still expect a final judgment-like ticket in future American elections, maybe it’s time to reexamine your worldview — because, is your strong stance really the silver bullet you're hoping it is?

MRITIKA SENTHIL is a sophomore from Columbia, S.C. Her email is mritikas@upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate