What’s the point of college if a robot can do our homework and pick up our skills better than we can?

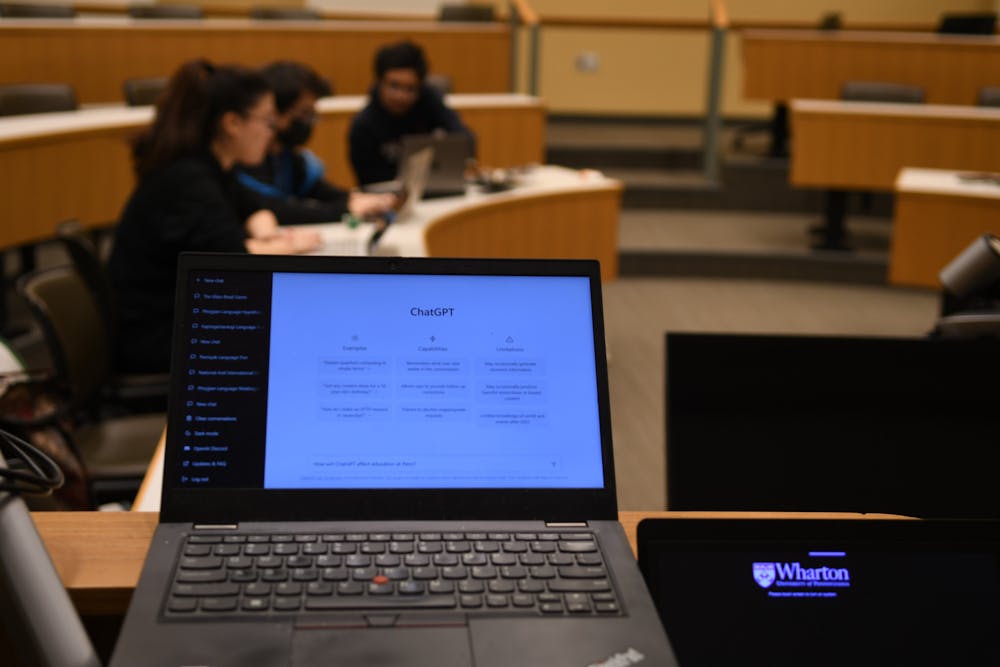

As first years try to choose a major that puts them on track to work at their dream jobs — or just any job — the growth of artificial intelligence has made the homework that comes with the major much easier. Whether you are ChatGPT-ing a physics problem, getting a summary of a book for an essay, or need code for your CIS class, artificial intelligence is truly omnipotent, a jack of all trades.

History has been named by the tools that have dominated it, just take the Bronze Age, Stone Age, or Digital Age, for example. Right now we are at the point where technology can become so powerful, that it can do what you are doing for you, instead of simply aiding.

Rather than excitement, a Pew Research study found that 52% of Americans feel concerned about the advent of AI, perhaps for its ability to transform virtually every industry and job market.

It’s not a new concern. Technological unemployment has been discussed as a threat since the 1700s when a British group of factory workers named the Luddites started destroying textile machinery because they felt their jobs were threatened by it. That concern has not gone away.

At the beginning of October, 45,000 port workers — people who load and unload the cargo ships — along the U.S. East Coast went on strike, the first International Longshoremen's Association strike in 47 years, in part to oppose automation which would get rid of thousands of jobs. Nowadays, most people in the ports operate the cranes that load and unload ships, but even this job can be automated to create a virtually humanless port. It’s truly awesome for the Penngineers who graduate with a degree in AI or the Wharton leaders who want to save money.

But, do we want a humanless port? That is the million-dollar question.

We need technology because we need to do things efficiently. We would not be able to support 8 billion humans if we were still producing food, clothing, furniture, and medicine the way we did in the 1700s.

We push the limits of technology because, first and foremost, we can, and because corporations always want to scale up and sell more. No amount of regulation can stop the desire for companies to maximize profits, and we benefit from this too when we get goods for cheaper due to reduced labor costs.

The greatest thing we can then become is adaptable. Our job is ultimately the gap that we fill. If technology fills that gap, we have no choice but to move on.

So long as self-driving cars have weaknesses, we’ll need drivers to bring them around. So long as we need to fix the cranes that eventually become automated, we’ll have people working on the ports. If one role disappears entirely, which is highly possible, we’ll use our adaptability as a weapon to find the next gap to fill.

As college students, when we know we can utilize technology for homework or to avoid a reading assignment, we might wonder why we should even try. It can build code faster, teach calculus better than your MATH 1400 professor, and generate ideas for you, in exchange for a one-minute input of a prompt. But if we stop there, we have stagnated. We use ChatGPT to fill in certain knowledge and skill gaps, knowing that there are others it can’t fill. Ultimately, it pulls from a collection of work that humans have done thus far to give us quick answers, but who’s asking the next big questions and creating the next original idea?

It’s us.

Technology can make many jobs easier like journalism, accounting, pharmacy and so much more, alleviating things like burnout by completing time-intensive tasks. But there are mistakes that technology makes and problems it can’t solve without us. When we’re trained to be skilled enough to use technology and knowledgeable enough to work around its weaknesses, we become better at our job, whether it’s providing more effective medical care or doing better reporting.

To those who make decisions regarding automation in industry and manufacturing, I hope that you consider your motivations behind these shifts. Will it improve the quality of your product or address a weakness in your process? Or will it merely allow you to pocket more from saving labor costs, growing the divide in wealth?

We cannot avoid the crane or the chatbot, but also cannot submit to either. In any field, realize that you are a dynamic and adaptable individual, beyond the constraints of an algorithm or task-specific machinery. Know that these tools cannot become the ultimate accountants or journalists or pharmacists, but are instead how we can become the better ones.

NAMRATA PRADEEP is a first year studying engineering from North Carolina. Her email is namratap@seas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate