The night of Nov. 5 felt like a fever dream. Sitting on my friend’s bed watching the sea of red on my laptop, I found myself comparing the stark differences between this United States election cycle and those I’d experienced in the United Kingdom. In the past year, I’ve watched the U.K.’s political pendulum swing dramatically — from Conservative dominance to Labour rule, with four prime ministers in just two years. But here, in my first U.S. presidential election, the stakes feel much higher, and the political landscape is even more polarized than I had imagined.

Democratic systems inevitably reflect the cultures they serve. Over the last decade in the U.K., political allegiance has become fluid, with voters regularly switching between Labour, Conservative, and other parties based on current circumstances during election seasons and policy proposals related to the National Health Service, immigration and the economy. I am old enough to remember the Conservative landslide of 2019 after a Labour Party implosion, while just this year, the Conservative Party was, in turn, unceremoniously thrown out of power by Labour. This fluidity, while creating electoral volatility, stems from a pragmatic approach to politics. U.K. voters typically view politicians as civil servants — fallible individuals temporarily entrusted with administrative duties rather than messianic figures.

The American approach could not be more different. Here, political affiliation often functions more like a cultural identity or even a form of secular religion. The “Make America Great Again” movement exemplifies this phenomenon — complete with merchandise, rallies that feel like revival meetings, and an unwavering dedication amongst its supporters that persisted even when Donald Trump was out of power. This unyielding commitment to a candidate fosters an environment where political loyalty transcends policy consideration, making it more about belonging to a team than evaluating ideas critically.

As I reflect on my first U.S. presidential election, three distinct aspects of U.S. political culture stand out to me, especially when compared to my experience in the U.K. First is the facade of progressivism within the U.S. political system — particularly amongst the Democratic Party — that masks a persistent resistance to change. While other nations worldwide — from the U.K. with its three female prime ministers to India with Indira Gandhi — have elevated women to their highest offices, some as early as the 1960s, the U.S.’s claims of meritocracy ring hollow against its track record — although women have come close twice, there has never been a female president.

The resistance to female leadership, particularly when combined with racial barriers, reveals uncomfortable truths about U.S. society. The American Dream’s promise that anyone can achieve anything loses its weight when examining these persistent glass ceilings. The election of Barack Obama in 2008 stands as an extraordinary exception and yet, the backlash and resistance to diverse leadership in the years since only highlight the troubling limits of the U.S.’s progressivism.

Compare this to the rise of Kemi Badenoch, Nigerian like me, who ascended to leadership within the British Conservative Party. While questions of tokenism certainly arise, the fact that a Black woman who wasn’t raised in the U.K. could ascend within the U.K.’s right-wing establishment demonstrates a pragmatism about representation that seems almost unthinkable in U.S. conservative circles. This isn’t necessarily about one system being more progressive than the other — it’s about fundamentally different approaches to political identity. In the U.K., political identities seem more adaptable, while in the U.S., they are often tied to entrenched cultural symbols and tribal loyalties.

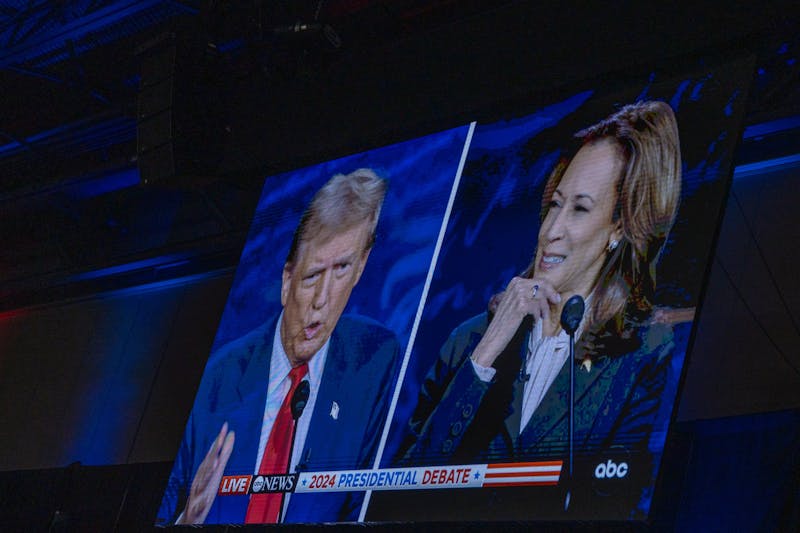

Second is the conflation of politics and entertainment, which feels almost alien to me. The regular appearance of politicians on shows like Saturday Night Live to directly promote their campaign represents more than mere public engagement. It suggests a bread and circuses approach where governance becomes indistinguishable from performance. While this might make politics more accessible, especially amongst Generation-Z voters who are engaged with pop culture, it risks reducing complex policy discussions to sound bites and viral moments: Did Kamala Harris being “brat” help her campaign at all?

Third, and perhaps most concerning, is the elevation of political figures to almost mythological status. This phenomenon crosses party lines, from the deification of the Obamas to the cult of Trump. When political leaders become brands rather than public servants, it fundamentally alters the relationship between citizens and their government. The transformation of political discourse into team-sport dynamics inhibits the kind of critical thinking essential to democratic health.

Looking ahead, I find myself wondering if these patterns are too deeply woven into America’s political fabric to ever truly change. As we stand on the precipice of another four years of a Trump presidency, I’m both apprehensive and curious. Will the fusion of entertainment and politics deepen further? Will governmental diversity regress? Will U.S. politics ever not devolve into a polarized shouting match? Whatever unfolds, I’ll be watching this next chapter of the U.S.’s democratic experiment with the unease of someone who has experienced democracy differently elsewhere.

ELO ESALOMI is an Engineering first year from London. Her email is eloe@seas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate