As members of the Penn community, we are accustomed to receiving occasional texts from the Division of Public Safety stating that scary things are happening around us. These UPennAlerts, as they are known, arrive automatically in the inboxes of faculty, staff and students.

In the past, I have always interpreted these messages to have our best interests at heart, encouraging us to steer clear of crime and violence. Alerts often report crimes in progress, such as “Armed robbery at 3400 Block Chestnut Street” or “Assault at 4000 Block Walnut Street. Police in pursuit of the suspect.”

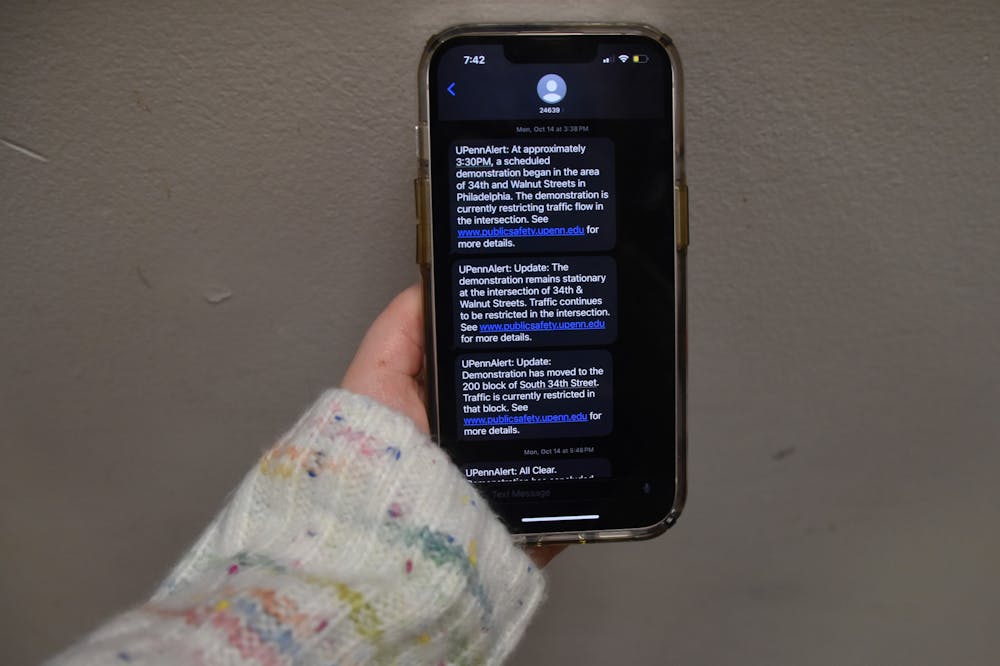

For this reason, I was puzzled when I recently received the following text:

“UPennAlert: At approximately 2:00PM, a scheduled demonstration began in the area of 30th and Market Streets in Philadelphia. The demonstration is proceeding west through University City in the direction of Penn’s campus. At this time, police are not aware of any instances of property damage along the march route.”

My initial reaction was that this must be a dangerous event, or why else would DPS be texting all of us about it? Yet, they also stated that they were not aware of any instances of property damage or, I assumed, violence. Nonetheless, the message produced the usual surge of adrenaline that I associate with hearing about a crime.

Shortly thereafter, a second text arrived:

“UPennAlert: UPDATE: The demonstrators are now marching south on 34th Street in the direction of campus. Police and security personnel are on site for the safety of all community members. Avoid the area, expect traffic delays, seek alternate routes.”

The idea that “the safety of all community members” was at risk and that we were supposed to “avoid the area” struck me as ominous. I was not aware of this protest’s purpose. But if I were involved in a peaceful protest in favor of something I believed in, I would be offended to be seen as such a dangerous entity. The repeated texts seemed to presume that protests are, by definition, a threat to public safety — even ones that are “scheduled” with DPS.

Finally, we received yet another text that the apparent threat had retreated from the campus area:

“UPDATE: All clear in the campus area. The demonstrators have passed the campus area and continue to move south; they are currently located at 34th and Grays Ferry Avenue. Police and security continue to patrol the area.”

To this day, I still do not know what this protest was about, but that made it easier for me to identify what bothered me so much about the texts. The point of all of these notifications seemed to be instilling fear in the Penn community. DPS implied that the protesters were potentially dangerous people, moving closer and closer to campus in a fashion that should send our blood pressure racing. This was despite the fact that this was “a scheduled demonstration.” People out to commit crimes seldom schedule them with DPS or the police.

A predictable consequence of this kind of overreaction will be that community members feel unsafe when, in fact, they are not. This seems especially counterproductive in combination with the Penn administration’s new emphasis on making sure people “feel safe.” This escalation in portraying protest activity as the potential for crime could then be used to justify preemptive action against lawful public assembly. The Penn community would do well to keep in mind that, to my knowledge, no students or faculty have been injured in protests on this campus to date.

In the United States, our Constitution guarantees us an enormous amount of freedom. Students and faculty should certainly exercise those freedoms responsibly. But taking them away in the name of “safety” treats college students as children in need of administrative protection from the views of those with whom they disagree. To become citizens in some future, less polarized country, Penn students need to learn how to live peaceably in a pluralistic democracy. Being part of a campus community that respects peaceful assembly and protest would be a terrific way to start. Learning to equate protest with danger is not.

It is worth remembering that the free speech movement in the United States began on a college campus. These spaces are extremely important incubators for ideas that have fundamentally changed our country, such as the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War protests. For those interested in a brief history of the importance of free speech on college campuses, I strongly recommend an eight-minute film titled “Bodies Upon the Gears.”

The free speech movement emerged from a coalition of liberal and conservative students who came together on one campus, even though they shared few political views other than the value of free speech and assembly. Despite the well-known issues that have divided our campus in the past year, I would hope that students and faculty could unite in their beliefs about the importance of restoring this freedom on our campus.

In the meantime, I strongly urge DPS to avoid treating peaceful protests as potential crimes. Otherwise, in order to abide by the University’s stated commitment to institutional neutrality, they will need to treat all protests as potentially dangerous, regardless of the cause advocated. Fears could be greatly lessened if DPS did not alert us about any protests except those involving violence or property damage. They should not be made to participate in inculcating unnecessary fear in the University community.

DIANA C. MUTZ is the Samuel A. Stouffer Professor of Political Science and Communication. Her email is mutz@upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate