When I saw the “Wharton School of Finance” trending on my X — the platform formerly known as Twitter — feed, I realized that the Penn name had made it into mainstream American politics. And unfortunately, this development cast a dark shadow over our University.

For those who didn’t tune in to the recent ABC presidential debate between former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris, both candidates mentioned the Wharton School within the first 10 minutes. After Harris referenced the Penn Wharton Budget Model when criticizing Trump’s tax and spending proposals, Trump responded, “I went to the Wharton School of Finance, and many of the professors, the top professors, think my plan is a brilliant plan.”

Here was the point of contention: when Trump incorrectly referred to his alma mater.

The Wharton School was initially known as the Wharton School of Finance and Economy from 1881 to 1902 before its retitlement as the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce in 1902 and a change to its present name at the end of the 1972 academic year.

So, of course, “The Wharton School of Finance” was the name of the institution when it granted Trump’s diploma in 1968. However, the former president’s lapse in recalling the University’s name of almost five decades speaks to a larger phenomenon: Penn students and alumni find significant meaning from the social capital granted by our University affiliation, sometimes more so than that from our shared experiences. Consequently, some of us have no incentive to actually engage with the University after graduation. We’ll probably be too busy with the pursuit of a new title signaling professional prestige.

Even the celebratory anthem “The Red and Blue,” which was written by a Penn alumnus and is performed at Commencement, Convocation, and other key University events, cannot complete a verse without attempting to validate our status by name-dropping other Ivy League schools:

“Fair Harvard has her crimson

Old Yale her colors too,

But for dear Pennsylvania

We wear the Red and Blue.”

And so, does this University offer us nothing but its name? Obviously, the answer is no. Any section of Penn’s course catalog — which features opportunities ranging from short-term travel to intensive independent study programs — can prove my point. The problem, however, lies in our campus’s lack of unity.

At Penn, those seeking centralized social interaction can only do so outside of their learning environments. I’ve always found the concept of rushing for membership in a fraternity or sorority at Penn strange. Time and time again, I’ve attended late-night open rush socials at random properties on Sansom Street, unaware of who the actual residents are. But although I have to bear an awkward sense of intrusion during these events, they are among the most ubiquitous open-access opportunities for me to branch out of Penn’s bubble of aspiring academics.

From the start, select first years are housed with those in their specialized degree programs. Subsequently, some students at the undergraduate schools — all of which we’re able to access when registering for courses — maintain an identity that doesn’t extend to the entire University (barring, of course, the Wharton internal transfer hopefuls). And so, it’s even more glaring when Penn’s attempts to centralize opportunities take a backseat.

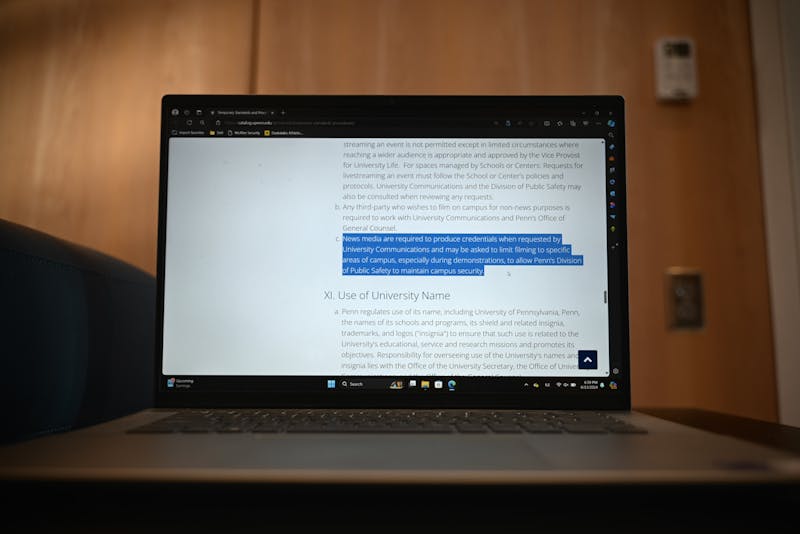

Penn’s largest student organizations operate without oversight from the University. For example, the Wharton Undergraduate Healthcare Club operates “the largest undergraduate healthcare conference in the nation” largely with the support of corporate sponsors and around 20 student volunteers. Even organizations like the Penn Undergraduate Biotech Society — which operate with Penn-affiliated labs and startups — offer pro bono services, and as such don’t have a formal relationship with Penn due to a lack of paperwork run by the University’s Human Resources department. This system conditions students to rarely turn to the University for guidance or resources aside from those that are department-specific. My point is not that Penn should extend an authoritarian hand over club operations, but rather that with the relative agency these organizations have, Penn was never in a position to establish a single platform for featuring student opportunities.

However, it was in this condition that Penn developed an Office of Religious and Ethnic Inclusion (Title VI), which functions as a “point of contact for … compliance related to religion, shared national ancestry, and ethnicity.” This new office follows the University Task Force on Antisemitism and the Presidential Commission on Countering Hate and Building Community. The establishment of the office is certainly a step forward in not only addressing political contentions, but also in streamlining communication. Now, Penn has yet to further address its fragmented communication with regard to student opportunities. This time, however, the problem will not solve itself through consecutive meetings followed by reports. Penn should recognize that Wharton’s newfound fame in popular media is the symptom of a deeper, yet easily solvable, problem on campus.

MRITIKA SENTHIL is a sophomore from Columbia, S.C. Her email is mritikas@upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate