With the spring semester coming to a close, there is much to look forward to: the flowers on campus are starting to bloom, seniors are graduating in May, and students just finished enjoying a much anticipated Spring Fling. However, for those of us who are not seniors, a concern still remains as we enter finals season and summer: course registration.

With advanced registration over, many of us may be worrying whether or not we’ll secure the classes we seek to take. I mean, who could blame us? After all, we diligently assessed the difficulty of each course considered, the amount of work it would require, and the so-called quality of the instructor teaching it. And as Penn students, the last thing we need is to be unexpectedly forced into a course we don’t want in an already harsh academic environment.

Nonetheless, while the numbers conveniently presented by Penn Course Review may help students determine a course plan that is manageable for them, it also shows a different trend. Penn students rate their instructors based on the complexity, not the quality, of the courses they teach.

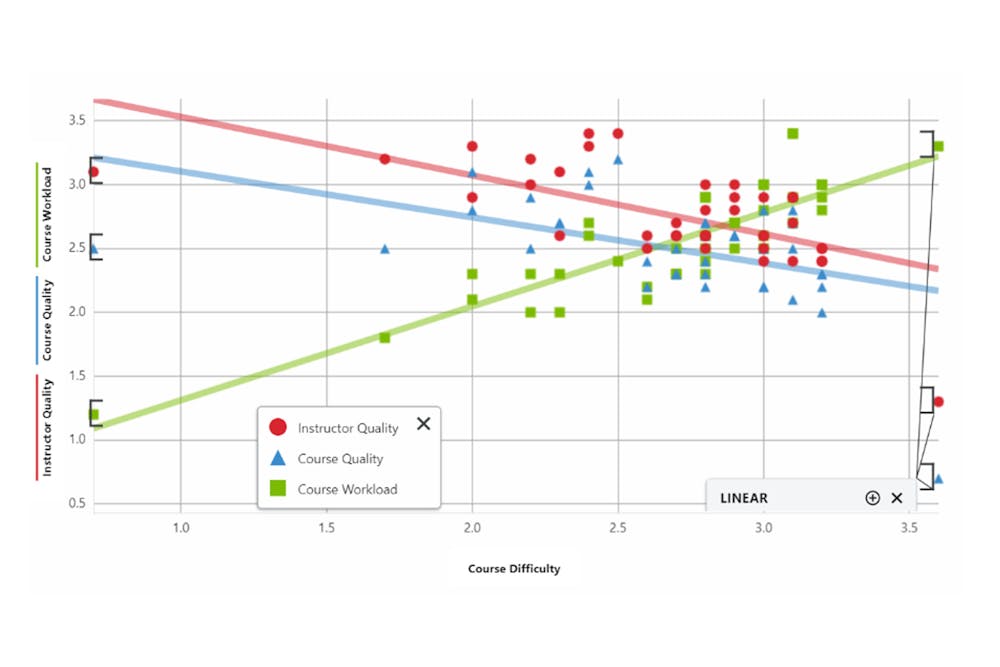

A collection of data obtained from Penn Course Review on 39 varied courses — spanning from Wharton’s business fundamentals to introductory science and calculus — shows that perceived instructor and course quality decrease as course difficulty and workload increase. In some ways, this makes sense. The easier a course is from a conceptual and practical perspective, the less time students think they need to allocate to that course. And in return for an easier workload and a greater possibility of doing well academically, students rate instructors favorably at the end of the term.

What is the problem with that? A lot. It misses the whole point of instructor and course ratings and undermines what learning is. From the viewpoint of academic developers, the quality of a course is determined by the clarity and practicality of its expected learning outcomes, and the effectiveness of the instructor is based on his or her ability to help students achieve those outcomes.

This assertion stands in stark contrast with how students rate the courses they’re taking and faculty that teach them; convenience and difficulty play a major role. And what results from that is bias favoring those who teach courses that tackle less demanding topics in a ‘friendly’ way. As you might imagine, this acts against those lecturers who teach ‘weeder’ courses that are heavy in theory and quite complex, projecting instructor ratings that may not be representative of the instructors themselves, but student preferences.

Imagine you have been sentenced to teach MATH 1400. Given it is an introductory calculus course, there is an exhaustive set of concepts and skills that your students must be able to apply by the end. And because you are teaching them computation and mathematics, you will require them to solve a series of problems — some straightforward, others less so — throughout the semester. Therefore, you will have to structure your course in a way that gives you enough time to cover all those objectives sequentially and assign students problem sets in between. You have to do all this while making lectures engaging.

Notice the predicament? While it is the instructor’s duty to engage students and present the material in a way that can be absorbed, with certain disciplines and courses there is only so much time for that before the instructor must yield to the priority of advancing learning outcomes.

Of course, this does not mean that your MATH 1400 course should be composed of sleep-inducing lectures and an unreasonably difficult workload merely because of the course’s unique circumstances. No matter what they teach, it is the responsibility of lecturers to account for the “background and motivation of the students, and the peculiarities of the discipline” if they are to facilitate progress on course learning objectives.

That being said, it is also the obligation of students to evaluate instructors based on how their knowledge has developed throughout the term and how the instructors helped facilitate that progress. While difficulty and workload are definitely fair metrics to some extent, they mustn’t take precedence over the outcome, which is the extent students achieved expected learning objectives.

ZAID ALSUBAIEI is a College first year studying economics from Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia. His email address is zaidsub@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate