Content warning: This article contains descriptions of violence and abuse that can be disturbing and/or triggering for some readers.

Armenia is a small country, one that many of you may have never learned about or even heard of. Today, it is a tiny, landlocked republic surrounded by unfriendly neighbors, a small remnant of what was once a sprawling, progressive, and productive homeland. It is a country that is difficult to spot on the map and one that has endured a seemingly unrelenting wave of strife and injustice. But Armenia is my country; to me, it is the center of our world. So today, on the 109th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, allow me to tell you about my country and how the Ottoman Turkish atrocities of over 100 years ago changed the trajectory of the Armenian race forever.

For nearly 3,000 years, Armenians inhabited the highlands at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, a sizable region extending to the shores of the Black, Caspian, and Mediterranean seas. As a consequence of the region’s strategic significance, numerous foreign invaders attempted to lay claim to Armenia, subjecting the peaceful inhabitants not only to barbaric attacks, but also to forced assimilation. And yet despite these extended periods of unrest and subjugation, the Armenians persevered. They developed their own language and alphabet and became the first nation (in 301 A.D.) to adopt Christianity as the national religion. Whether in independence or under the yoke of foreign powers, Armenians built cities and churches, developed culture and trade, and brought advancement to their land. Such was the case during the time of the Ottoman Empire, where Armenians significantly influenced Turkish commerce, industry, architecture, and the arts.

In 1915, at the height of World War I, the declining Ottoman Empire fought on the side of the Central Powers. During this time, three nefarious members of the Young Turk movement — Talaat, Enver, and Jemal Pashas — implemented a plan for Turkification aimed at strengthening the waning empire by creating a homogenous Turkish civilization. Of course, this desire for an all-Turkish existence on the historic Armenian lands could not be perfected without removing all existence and any trace of the vibrant, successful, and large Armenian population.

On April 24, 1915, the Young Turk regime executed what is now referred to as the first major step in the timeline of the Armenian Genocide. On that day, Ottoman Vizier Mehmet Talaat, one of the three Pashas, ordered the arrest, capture, and eventual execution of 250 Armenian intellectuals and politicians in Constantinople (now Istanbul). In reality, however, the massacre of the Armenians had begun years earlier, with thousands of deaths occurring from 1894 to 1896 and in 1909. Still, April 24 is generally considered the dawn of the darkest period in Armenian history.

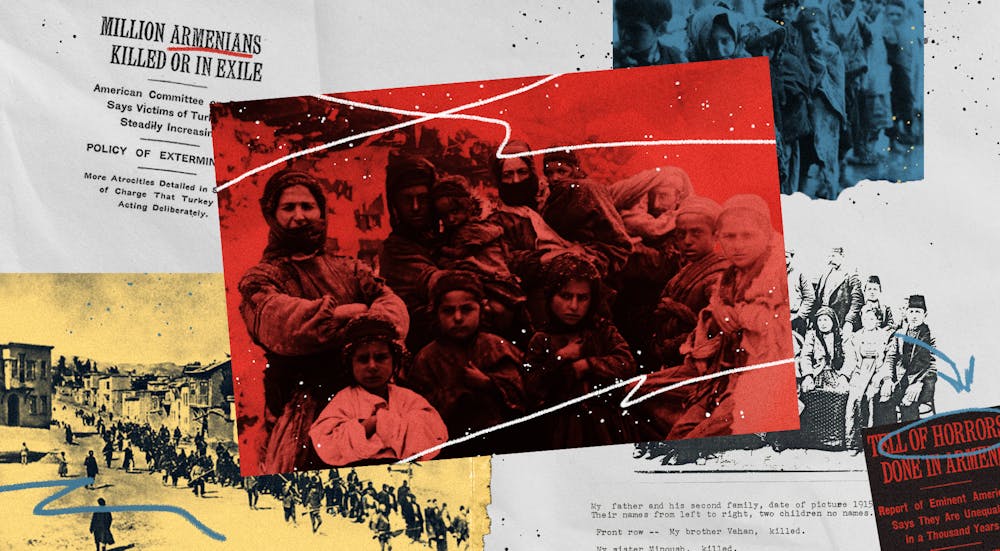

The removal of the Armenian people’s key intellectuals and leaders was designed to expose and render the rest of the population defenseless, including women, children, and the elderly. Soon after, Turkish gendarmes began their plan for the extermination of the entire Armenian population, immediately killing countless adult males and ordering the deportation of the rest from their ancestral villages into so-called “relocation centers” across the Syrian Desert. Armenian women, children, and elderly were marched to their death through the barren and unforgiving desert of Deir Zor. No water, food, or shelter was provided. Young Turk officials oversaw the separation of men and teenage boys from the deportation caravans, and then proceeded to end their lives with sweeping and merciless executions. Meanwhile, women and children endured grueling journeys through mountainous terrain and desolate expanses, where many fell victim to kidnapping, rape, and fatal exposure to the scorching sun.

The Turkish gendarmes’ brutal methods — including drowning, cliff tossing, crucifixion, starvation, and immolation — left a trail of Armenian corpses strewn across the Caucasus landscape within a matter of months. Survivor testimony has explained in detail the morbid brutality of the Turks. It is recorded that “on October 24, 1916, Deir Zor’s police chief Mustafa Sidki, ordered some 2000 Armenian orphans carried to the banks of the Euphrates, hands and feet bound. They were thrown into the river two by two to the visible enjoyment of the police chief who took special pleasure at the sight of the drama of drowning.” This was not a one-time atrocity. The U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire at the time, Henry Morgenthau, stated that at Kemah Gorge, “hundreds of children were bayoneted by the Turks and thrown into the Euphrates.” Between June 10-14, 1915, 25,000 Armenians were killed, and the victims were thrown off the steep cliffs of Kemah Gorge. To this day, a visit to these regions reveals miles upon miles of skulls and bone fragments, a somber reminder of the atrocities perpetrated by the Turks.

Between April and September of 1915, the 3000-year-old Armenian land — the Armenian provinces of the East and of Asia Minor — was methodically emptied of its population and wiped off the map. Roughly 60 to 65 percent of Armenians, totaling more than 1.5 million individuals, perished. Many surviving orphans faced forced marriage or conversion to Islam, raised without their Armenian identity. Armenian properties — including schools, churches, businesses, and personal belongings — were either demolished or seized by the government and redistributed to Turks.

Morgenthau wrote in his memoirs: “When the Turkish authorities gave the orders for these deportations, they were merely giving the death warrant to a whole race; they understood this well, and in their conversations with me, they made no particular attempt to conceal the fact.”

Yet the diplomatic records, official archives, photographic evidence, aid missions, and eyewitness testimonies still have not been enough for reparations in the modern day. The Turkish state still completely denies the horrors of 1915. It utterly rejects any accountability or criminality for the genocide of over 1.5 million Armenian martyrs.

Denial tactics have evolved over time, initially refuting the genocide outright and shifting blame to scapegoats like the Kurds and criminals of the Empire. Subsequent strategies included diplomatic pressure, censorship of media and academic discussions, and attempts to rewrite history through privately-funded foreign “scholars.” Turkey even passed a bill to ban the usage of the term “Armenian Genocide” within its borders, threatening criminal prosecution and imprisonment for anyone who mentioned the term or related events.

The Turkish government has also leveraged its geopolitical alliances and economic power to silence recognition efforts by foreign governments, employing lobbyists, defense contractors, and multinational corporations. Furthermore, Turkey has funded academic publications and established Turkish Studies programs to propagate denialist narratives, even influencing appointments at prestigious institutions like Princeton University. Despite international recognition of the genocide by numerous countries, Turkey continues to exert significant pressure to suppress acknowledgment of this tragic, unresolved chapter in history. The “Encyclopedia of Genocides and Crimes Against Humanity” considers the denial of the Armenian Genocide “the most patent example of a state’s denial of its past.” Imagine the government of Germany denying — to this day — that the Holocaust ever occurred.

As a consequence of the Armenian Genocide and post-war politics, Armenia was whittled down to a tiny landlocked republic, which was ultimately incorporated into the former Soviet Union. Today, though freed from the iron fist of Soviet rule, Armenia is but a fraction of what it once was. On the other hand, because of the mass deportations, survivors of the atrocities had no choice but to establish roots in other countries, such as Syria, Lebanon, France, the United States, and Argentina. In these and other nations, survivors developed Armenian communities that provided a measure of comfort, solace, and hope. The Armenian diaspora is the direct result of the genocide, and it is this diaspora that continues to fight for recognition. Currently, more Armenians live outside of the homeland, with only roughly three million actually inhabiting Armenia proper.

Armenians all over the world take April 24 as a day to call on every global citizen to remember the unrecognized genocide of 1915. Today, I call on you, as a member of the Penn community, to do your part as a person committed to justice and education, to remember the 1.5 million martyrs of the Armenian Genocide. Stand with history and stand with Armenia, today and always. For ways to do your part in helping the Armenian cause, please consider following this link.

At the conclusion of his Obersalzberg speech on Aug. 22, 1939, a week before the German invasion of Poland, Nazi leader Adolf Hitler stated, “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

Well, I do. And it’s high time that you do, too.

SOSE HOVANNISIAN is a College sophomore majoring in communications and minoring in history and consumer psychology from Los Angeles, Calif. Her email is sosehova@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate