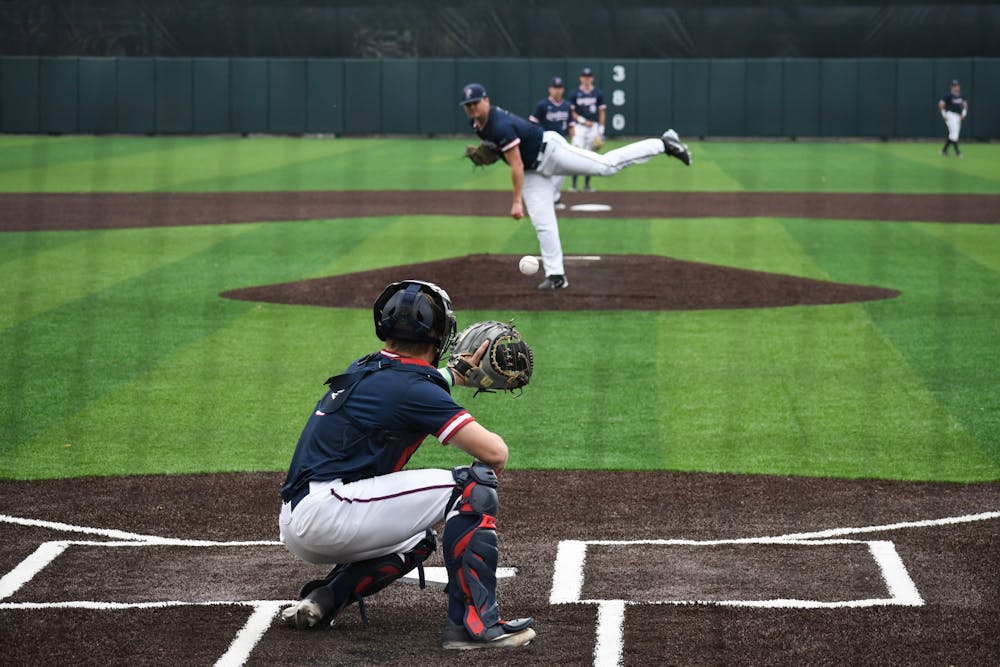

Penn baseball's starting catcher Jackson Appel is arguably one of the top catchers in the Ivy League. He was named second team All Ivy last season and has been on fire this season with a .858 OPS and a .316 batting average.

However, while he has lit up the stat sheet, one of his biggest impacts on the team doesn’t show up in the box score. His ability to foster a strong dynamic with Penn’s pitchers has helped the team maintain a 4.23 ERA — by far the lowest in the Ivy League with Columbia coming in at second with 6.11.

For sophomore right-handed pitcher Ryan Dromboski, who is in his first season as a starting pitcher for the Quakers, having a strong relationship with Appel has allowed him to flourish with a 3.74 ERA this season. He highlighted the importance of having a catcher who knows his habits and what pitches he likes to throw in different counts. For the hard-throwing righty, his go-to punch-out pitch is his slider — which has helped him reach 31 strikeouts this season, fifth most in the conference.

“When I get to a two strike count, [Appel] knows to mostly set up outside and be like 'Yep here comes a slider, I’m ready to go for it.'” Dromboski said.

According to pitching coach Josh Schwartz, catchers need to know the trends of every pitcher on the staff — including what each of their pitches looks like and how to set up behind the plate to make them as effective as possible. He added that catchers need to adjust to pitchers. Dromboski, for example, incorporates pitches that tend to have a lot of movement in which Appel is skilled to expect.

“I think if you asked Appel what he would want Dromboski to do, he would say throw every ball down the middle and let them move,” Schwartz said.

Schwartz added that in addition to telling Dromboski to aim for the middle, Appel might consider setting more towards center to help Dromboski be more effective.

At points in the game when things aren’t tipping in Penn’s favor and the pitcher is struggling, Appel is often tasked with going out to the mound to help settle him down. Appel said that over time, he has developed different approaches on how to handle different pitchers.

“Some guys you want to tell them to lock it in and be a little harder with them," Appel said. "But then some guys just need a little break, so I’ll just talk about anything, whatever’s on my mind even if it is not baseball-related at all. Sometimes that actually helps people.”

Appel has a whole checklist of information he needs to know to help pitchers be at their best. It might be easy to memorize it all for one pitcher like Dromboski, but on a staff that already has six pitchers who've thrown double-digit innings through 19 games, learning all the intricacies of each pitcher is not an easy task.

“The catcher has to know the pitcher inside and out,” said Schwartz. “He has to know what his tendencies are, know where his failures are, know how to rile him up or calm him down or say the right thing. He has to know what's sharp or weak for that day, and what the past history of his pitches has been.”

Appel added that it takes a lot of practice to build a strong rapport with the pitchers. He catches them often throughout the offseason to learn their mechanics better and build chemistry.

“I’ve caught all of them so many times at this point," Appel said. "We do a lot of work with them. Just through repetition you end up knowing what’s good for each guy.”

Despite all the important information that goes into a successful pitcher and catcher relationship, some might argue that the most important factor is trust. Dromboski said that he knows a critical part of earning a catcher's trust is not crossing them up. When a catcher expects a curveball, for example, and ends up getting a fastball that's 10-20 miles per hour faster and with a lot less movement, it can be dangerous.

At the college level in particular, blocking is an essential component of a strong pitcher-catcher relationship. The college strike zone tends to be wider and pitchers understandably have less command over their pitches than at the major league level, so having a catcher that can prevent past balls is more important than framing pitches and stealing strikes.

Schwartz explained that if there was a runner on third and the best pitch in the given situation was a low breaking ball, the pitcher needed to be confident that the catcher could block the ball and prevent the runner on third from scoring. The pitcher also has to trust that their catcher's arm is strong enough to throw out runners trying to advance.

The list of demands on Appel and the rest of Penn's catchers is lengthy, but if they can do all that, Schwartz has one last request.

“If a catcher can hit and run well," he said, "and really get it done on that side of the ball like Jackson Appel can, then I’m a happy camper.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate