I don’t know what I expected after I watched the October 22nd Pennsylvania Senate debate, and saw Former Lt. Gov. John Fetterman labor through his responses, struggling to defend himself against accusations lodged by his Republican opponent, Mehmet Oz. I knew the world would not respond kindly — try as we might, we are not yet accustomed to the idea that a politician need not be perfectly articulate to succeed at his job. But I didn’t know whether Fetterman’s debate performance would cost him the upcoming election. I was not sure that we, as Americans, were ready to elect a man with an auditory processing disorder to high office.

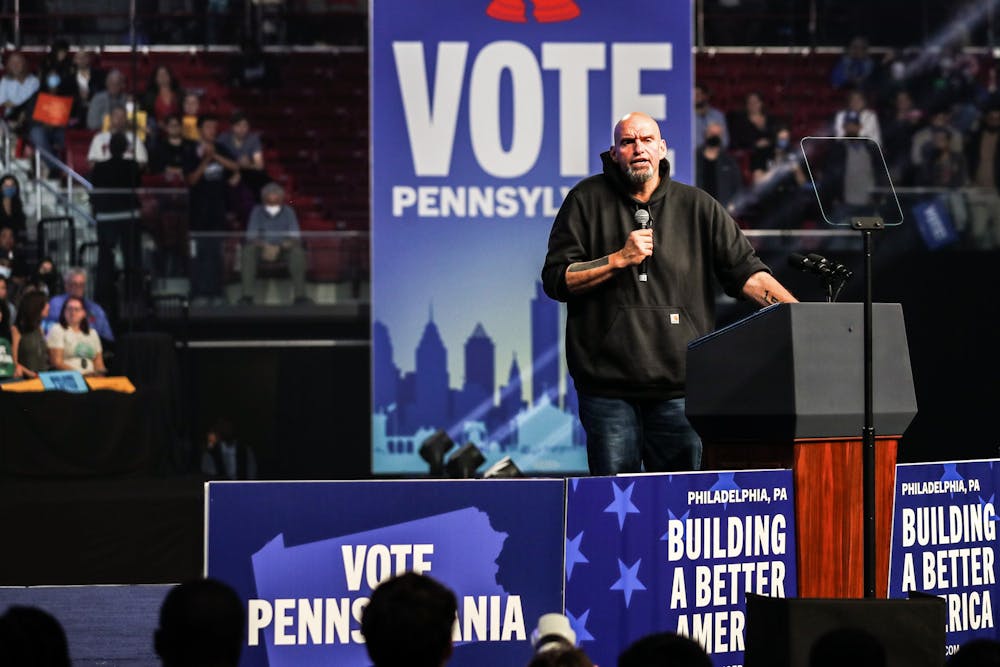

It has been a month since Fetterman’s victory and appointment to the Pennsylvania Senate seat, but my heart still bridles with pride when I think of the senator-elect’s address to the nation, following his win. The Reading, Pennsylvania native spoke out to a crowd of supporters, all of whom had gathered in the wee hours of morning to celebrate the politician’s success. “This campaign has always been about fighting for everyone who’s ever been got knocked down, that ever got back up,” Fetterman said to the mass of voters. “This race is for the future of every community across Pennsylvania… I’m proud of what we ran on. Protecting a woman’s right to choose, raising our minimum wage, fighting the union way of life. Healthcare is a fundamental human right. It saved my life, and it should all be there for you when you ever should need it.”

In this last line, Fetterman referenced the ischemic stroke he suffered in May, just four days before the Democratic primary. The former Braddock mayor was still in the hospital when he received news of his win as Democratic nominee for the Pennsylvania senate race. Following his stroke, Fetterman developed an auditory processing disorder — a disorder which makes it difficult to perceive subtle sound differences in words. The Pennsylvania native also developed aphasia, a language impairment disorder that affects the expression and understanding of spoken words.

Aphasia and auditory processing deficits are common in stroke survivors, with the former affecting one-third of all patients. These disorders can make it challenging for survivors to process the words of others, or to come up with appropriate responses.

These speech difficulties were apparent in Fetterman’s October formal debate with Republican challenger, Oz. During the dispute, the senator-elect stumbled when asked to address Oz’s accusations that he wasn’t medically fit to serve as senator. Fetterman also seemed to have trouble patching responses together in the timed, rapid-fire manner typical of formal debates.

Still, the politician prevailed, winning Pennsylvania by a margin of 263,000 voters, even after pundits on both sides of the political spectrum criticized his performance, challenging his ability to fill the Pennsylvania senate seat.

But inquiries into Mr. Fetterman’s competence as a U.S. senator indicate a larger misconception about auditory processing disorders and disabilities in general. Central auditory processing disorders simply affect the brain’s ability to hear language in the “usual way.” Auditory processing impairments are not cognitive deficits, nor are they learning disorders. They do not affect an individual’s ability to understand meaning.

This fallacy that disabilities connote intellectual impairment is more common than you’d think. Misconceptions about disabilities abound even among the more progressive and educated, says Lex Gilbert, a College sophomore and the founder of the Disabled Coalition at Penn. As an umbrella organization for all disabilities, the Disabled Coalition works to advocate for the University of Pennsylvania’s disabled community and build authentic connections among their ranks.

Gilbert formed the coalition after discovering a clear need for safe spaces among disabled students. As we met on a Monday night to discuss their work, Gilbert recalled a situation in which they were approved for classroom accommodations — only to be told by a professor that they need not receive accommodation for that class because they were “smart.”

“I was shocked that she thought me being smart would have anything to do with my disability status,” Gilbert said.

Unfortunately, ableist attitudes such as these are prevalent throughout our society. Gilbert argues that some of the misconceptions about disabilities come from an unwillingness to discuss what it means to struggle with one. “I think there’s an ableist narrative where disability isn’t really discussed in able-bodied households… It’s not ever talked about so people don’t know what it’s like to have a disability or what it means to have a disability.”

Gilbert argues that even beyond the household, at the corporate level, most diversity, equity, and inclusion teams aren’t ready to do the work to combat ableism. Gilbert contends that most diversity, equity, and inclusion teams are not formed with accessibility in mind. “No one is starting a DEI program and looking first to accessibility. They’re looking first to racial identities, and then maybe they’re looking to sexual orientation, and then maybe after that they’re looking to gender identity, and then maybe after that — ten years down the line — then they’re looking at accessibility.

“Of course, being a person of color and a member of the LGTBQ community, I think those are important as well. But I think that DEI teams often forget that accessibility is a part of DEI. I just wonder — and I want to throw the question back out — what would it look like to center accessibility?”

When it comes to questions like these, more work must be done. Perhaps Fetterman’s appointment to the U.S. senate indicates a shift in the right direction when it comes to challenging misconceptions about disabilities. Still we, as individuals, must work to uproot our own inherently ableist beliefs.

Gilbert says there are plenty of ways students can get involved in disability justice and target their own false beliefs about disabled people. “Follow disabled content creators. I know pretty much everyone who’s reading this article is on TikTok, Instagram et cetera. Maybe you’re still on Facebook. There are disabled content creators on all of those platforms and there is a disabled content creator for whatever kind of content you’re interested in.”

The Disabled Coalition president also encourages students to engage in open conversations with differently-abled people in their own lives, whether it’s a friend or a family member. If you don’t have someone you’re comfortable talking to, Disabled Coalition events are a great resource to learn more about accessibility justice.

“We all have to start somewhere,” Gilbert told me in closing. “And I think all of us as humans, to a certain extent, understand that.”

JULU NWAEZEAPU is a College sophomore studying behavioral and computational neuroscience from Chicago. Her email is julunwae@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate