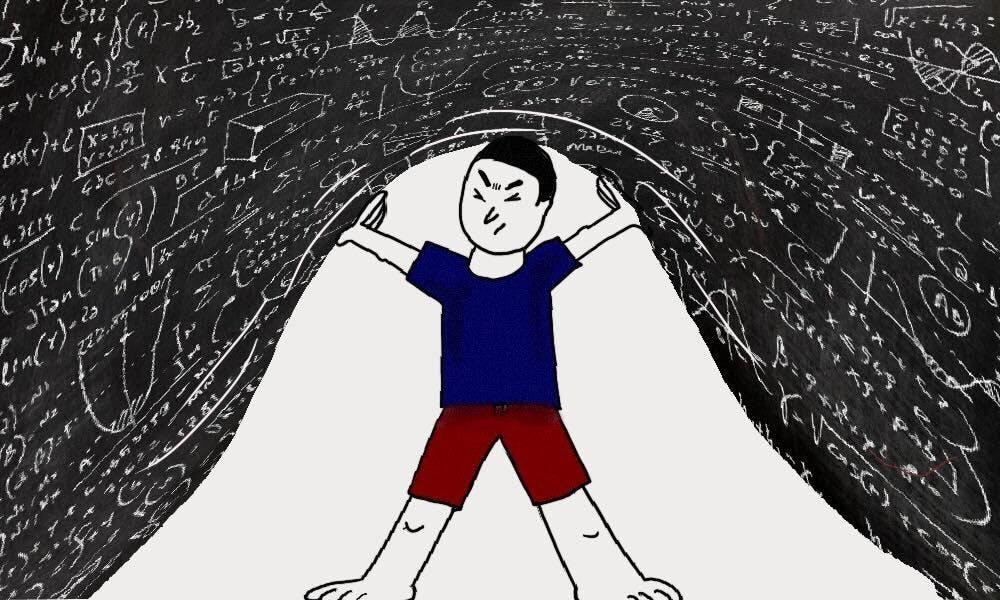

Many of my midterm exams at Penn so far have been emotional rollercoasters. Going toward the end of my first year at Penn, I’m finding a common pattern after taking each exam: thinking that I absolutely failed it at first, until the professor releases an announcement saying that the exam will be curved. Talking to many of my friends, I’ve learned that I’m not alone in feeling strained by this recurrent situation. Although everyone appreciates getting a curve on any assignment, I can’t help to point out a much simpler solution: Create exams with more reasonable levels of difficulty.

Overly difficult exams inherently indicate the fact that the scope of exam problems is inconsistent with the material taught in this class. This results in assessments that evaluate aptitude instead of diligence and preparation. The purpose of an exam is to check a student’s understanding of the material discussed in class and their ability to apply those concepts — not their ability to solve convoluted problems that are only tangentially connected to the class. From my own experience last semester, I often found myself struggling with an exam problem only to later discover that the topic in question wasn’t ever discussed in prior lectures.

Granted, many students would study more effortfully when a more difficult exam is administered. However, an overly difficult exam fails to serve as a proper assessment if the majority of the class fails it. If the entire class is going to ultimately get their grade curved, making these exams less challenging in the first place would greatly improve the mental wellness of many students by reducing their performance anxiety after each exam.

Moreover, curving itself is problematic because it undermines the implementation of a fair grading system. The purpose of having cutoffs for different grades in an exam is to enforce a marking line for objective level of mastery of the material. However, a curve in an overly difficult exam changes the purpose of cutoff lines such that they reflect only the performance of the whole class instead. Such a practice unfairly demarcates one group of students from another based on the relative performance of the class rather than the independent learning progress of each student. As most Penn professors believe that all students can excel in a class simultaneously, curving the exam undermines such a belief. Penn professor Adam Grant discussed the idea of limiting the portion of a class that can excel in his New York Times column: If, in a class of 10 students, the professor implements a forced curve that only allows seven students to get an A, the remaining three students would be unfairly punished. Similarly, in a situation where an exam is overly difficult, the opposite happens — some students would arbitrarily, and unfairly, obtain A’s among a notoriously poor class-average raw score. In this case, people whose grades were boosted by the curve gained an unfair advantage granted by the poor performance of the entire class, as opposed to their objective level of subject mastery.

While advocating for less difficult exams, I’m not claiming that all courses at Penn have this problem — as many professors still administer exams that are appropriately challenging and fair. However, a proper end goal would be that every class offered at Penn creates a fair and healthy learning environment.

My ”Introduction to Experimental Psychology” class last semester offered an exemplary model of why less difficult exams are more conducive to student learning. The exams in that course heavily focused on materials mentioned in the lectures, and points were fairly rewarded to those who paid close attention to the materials verbally mentioned. Instead of creating notoriously difficult exams that students struggled to even finish on time, the multiple-choice format provided every student ample time to properly reflect and apply the knowledge they previously learned.

It is impossible to make every exam appropriately challenging, and sometimes one batch of students may perform much better in a given year compared to previous years. However, it is still important to acknowledge that excessively difficult exams can only cause more harm than benefit. Penn students constitute some of the most talented youth across the globe. If these students find themselves struggling on exams, perhaps the exam was too difficult to begin with.

TONY ZHOU is a College first year from Zhejiang, China. His email address is hyy0501@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate