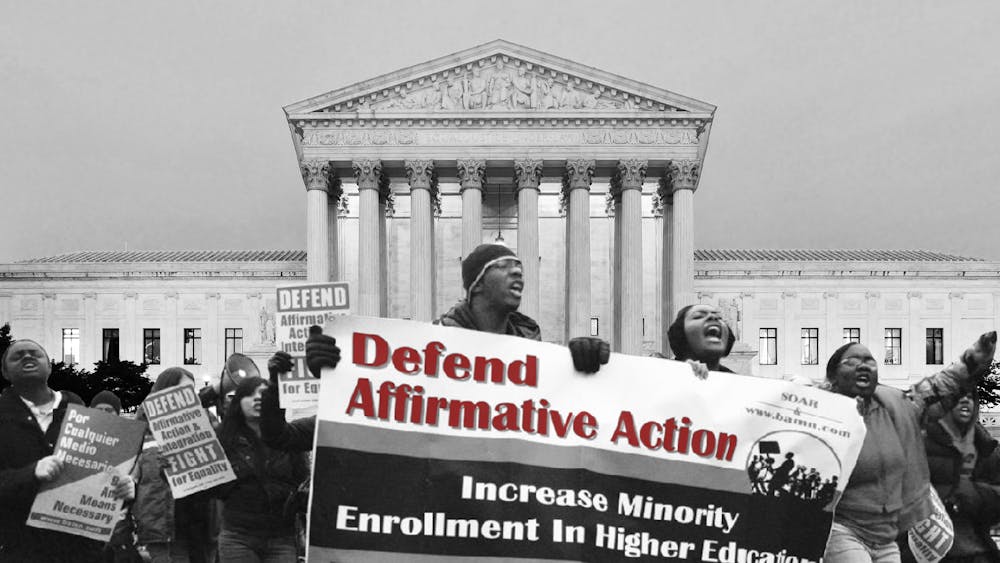

Photo Courtesy of Mapping Ignorance

Credit: Erin MaOn Monday, Jan. 24, 2022, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a case that could redefine American universities’ race-conscious admissions programs, endangering the future of affirmative action in higher education.

Students for Fair Admissions, the plaintiff, claims that Harvard University unfairly uses race as a factor in admissions to penalize Asians and reduce the number of Asian Americans on campus. Edward Blum, the founder of SFFA, asserts that Harvard and University of North Carolina have “racially gerrymandered” the undergraduate class to achieve certain prescribed quotas on race.

Conservative justices have long viewed affirmative action programs with skepticism. With a conservative supermajority of six judges in the Supreme Court, the case will likely set a precedent and ban the decades long practice of considering race as one of a number of factors in evaluating applicants.

But despite the tremendous progress this country has made in achieving racial equality, systemic and structural racism is still extant today, regardless of one’s class. Protecting affirmative action is still important to address the distorted opportunity structure today.

Race still plays a determinant role in outcomes even for people in the same class. White families still have more investment opportunities and accumulate more wealth over generations, a key component for middle-class whites being able to buy their first homes. In addition, middle-class Black families are more likely to live in lower-income neighborhoods than white middle-class families.

Even middle- and upper-class Black families face worse intergenerational mobility than their white counterparts. A recent study shows that Black Americans born in households with income above the national 80th percentile face nearly the same probability of falling to the bottom 20 percent as they do to remain in the top 20 percent. In comparison, white adults are five times more likely to remain in the top 20 percent as they are to fall to the bottom 20 percent. Clearly, household income and class cannot explain the comparatively shrinking upward mobility Black youths face today. Black Americans are less likely than their white counterparts to pass their class status to the next generation and are more likely to experience downward intergenerational mobility.

Affirmative action opponents argue that admissions policies should address economic disadvantage, not race. However, race and class today are still so intertwined that one cannot be solely explained without the other.

Research from former Princeton University professor Alan Krueger and Mathematica Policy researcher Stacy Dale shows that Black and Hispanic students have long-range benefits from attending brand name or elite universities such as a positive improvement in their future earnings. In contrast, the research is unclear whether white, non-low-income students attending elite colleges make a difference for future earnings.

In other words, affirmative action remains affirmative today. It affirmatively helps students of color improve their socioeconomic standing, which is still worse than their white counterparts. It affirmatively raises intergenerational mobility. And it affirmatively diversifies perspectives on campus.

This is not a zero-sum game. White and Asian American students also stand to gain in attending an institution that actively includes the voices of underrepresented minority students. It increases the likelihood for college students to socialize with peers of other races and backgrounds.

As a top-ranked institution for higher education, the University of Pennsylvania has the responsibility to ensure that people of all ethnicities, backgrounds, and genders have the same ability and probability of reaching success.

Right now, this assurance is under attack.

While public universities must comply with the Supreme Court’s rulings on affirmative action, private institutions will also be impacted. Private entities such as Penn must comply with federal statues, including rulings on race discrimination, to continue to receive federal money. Every year, Penn and other Ivy League schools receive tremendous amounts of money from the federal government. A report in 2017 revealed that the average amount of money received annually by the Ivy League schools exceeds the amount of money received by 16 of the 50 states.

If the court repeals affirmative action, it would mean that private institutions have to make a difficult choice between receiving federal funds or continuing race-conscious admissions.

I am not saying that Affirmative Action is the perfect solution. Far from it, such policies reflect the still problematic reality of simultaneous racial and economic stratification in the United States. Race is only one data point that makes up hundreds of factors college admissions offices consider when holistically reviewing an applicant’s story. Rightfully so, race is still one of the many factors that reflects the unfair and lopsided opportunity structure in the United States today.

Instead of attacking the chances of underrepresented minorities to enter colleges, we should focus on banning special treatment given to the wealthy and legacies in elite colleges. The median family income of students from Penn is $195,500, and 71% of Penn students come from the top 20% income distribution. Legacy students are also disproportionately represented in the pool of admitted students at Penn. In 2017, 16% of the 7,074 applications received in November were identified as legacy students, but 25% of the admit pool had legacy status.

Challenging affirmative action will not end the distorted opportunity structure in many elite colleges. Rather, it hurts the policy that seeks to equalize the structure.

SAM ZOU is a College junior studying political science from Shenzhen, China. His email is samzou@sasupenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate