I am Black. I was born in the United States. I am a college student. And I never learned about the Tulsa Massacre in school.

My first encounter with Tulsa was a YouTube video. Watching the video brought on a plethora of emotions: sadness, confusion, and, surprisingly, regret. I grieved the years I spent unaware of the deeply entrenched systemic and economic racism that destroyed the livelihood of a progressive African American establishment. Why wasn’t I informed of such a grave injustice? How did I remain woefully ignorant?

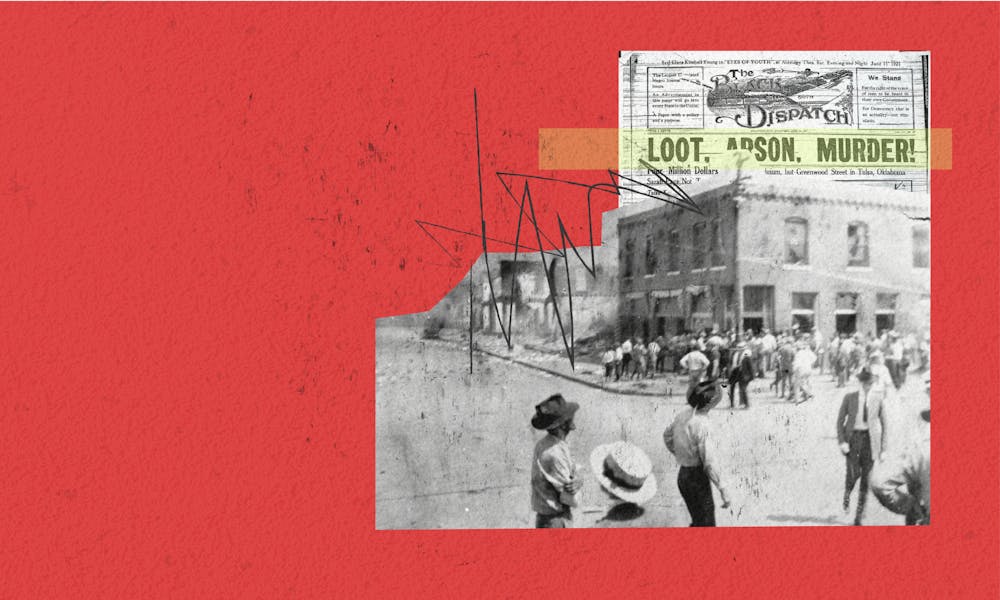

The Tulsa Massacre’s history existed for a century before I learned of its deleterious effects. The Massacre was spurred by a mob after a white woman accused a Black man of assault. A progressive Black establishment in Tusla, Oklahoma's Greenwood District was subsequently torched by a mob full of violent and armed arsonists. Reporting on the massacre was limited at the time, though hundreds of people died and many more were left without homes.

How could such a significant portion of American history remain hidden? Why do we refuse to alter our history books or integrate it into college economics courses? Business schools have a social responsibility to educate their students about the sociological and environmental factors external to the balance sheets, supply curves, and net present value calculations we laboriously analyze. According to the “Economic State of Black America” report from the Joint Economic Committee, 97% of respondents underestimate the gap between the wealth held by Black and white families. Our educational system is lacking in its ability to communicate the racial impact on access to capital. Like it says in the report, “the majority of Americans fail to recognize the magnitude of these problems.”

The Tulsa massacre furthered the racial wealth gap, which led to disparate quality of life outcomes. From access to education, healthcare, and even venture capital, your race is the primary factor that determines your quality of life. Black entrepreneurs currently receive less than 1% of venture capital funding. In 2019, the US homeownership rate was 64.6%,. For Black Americans, it was 42.1%. In January 2020, the unemployment rate for Black Americans was 6%, 1.9 times higher than the national average.

On this fourth of July, I’m thinking very critically about my identity as a Black American, the Tulsa Massacre, and what our educational institutions can do to communicate its relevance and importance to studying inequities in business. It’s time we began discussing and dismantling the Tulsa Massacre’s impact in college courses. We can modify our economics and entrepreneurship classes to include this important moment in history. Manifesting a visionary, equitable, and American curriculum requires a commitment to sharing the truths behind our current state, no matter how harsh or painful they may be.

My introductory economics courses at Wharton never discussed the hidden sociology that has influenced this long-standing and racially influenced wealth gap. Business is sociology. The business world is a product of the historical landscape that surrounds it. The lines between scholarly disciplines blur such that economics isn’t siloed from sociology, Africana, and urban studies. And yet, we’ve discussed urban real estate without mentioning gentrification and learned about the factors of production - land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship - void of the unimaginable impact race has on all four distinctions. Students should not graduate from top institutions without a comprehensive understanding of the racial impact on economic measures of wealth and well-being, especially since these institutions intend to shape the next generation of leaders across all factions of society.

Discussing and teaching the factors relevant to the Tulsa Massacre is vital to a genuine understanding of the wealth gap and the ideologies that combat it. In a course I took in the spring, we debated the merits of Universal Basic Income (UBI). We talked about its pros and cons, and its potential effects on our existing social systems. Our arguments were framed from a bipartisan perspective, instead of comprehensively acknowledging the relevant racial and sociological forces. Factors like UBI illuminate the conversation surrounding reparations and thus must be taught in conjunction. Without learning about the Tulsa Massacre and similar events, business and economics students won’t have the capacity to analyze social change efforts from interdisciplinary perspectives.

The Tulsa Massacre can be used to introduce the often unacknowledged struggles faced by Black entrepreneurs. Black Wall Street, as the area was known, was home to theaters and small businesses that were all Black-owned. For many, entrepreneurship is a vital component of the quintessential American dream, a chance to open a mom-and-pop store, manifest an innovative vision, or cultivate generational wealth. The destruction of Tulsa’s Black Wall Street was the sudden destruction of that dream. Today, Black entrepreneurs still face barriers to manifesting that dream, whether through dealing with credit or loan discrimination or the aforementioned limited access to venture capital. It’s time that we bring their stories back into the limelight and refocus our efforts on supporting Black entrepreneurship. Universities can teach about Black Wall Street alongside launching and marketing innovative programs to encourage entrepreneurship among multicultural students.

In the three years I've attended Wharton, I’ve wanted to see multiculturalism acknowledged in business. Our history is rich and full, a pillar of American history, and should not be overlooked by economics or any curriculum. Analyzing Tulsa's Black Wall Street exemplifies two realities of the Black economic experience: our entrepreneurial spirit and desire for self-sufficiency, and the barriers we face to acting upon these strengths. It’s time our classes catered to these realities. This fourth of July, there’s nothing more American than ensuring multicultural and underrepresented narratives are adequately accounted for in every academic discipline.

SURAYYA WALTERS is a rising Wharton senior concentrating in management and marketing with a minor in urban education policy from New Rochelle, N.Y. Her email address is surayyaw@wharton.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate