There was an uneasy eeriness in my Philadelphia bedroom on Oct. 18, 2020; it was my first birthday in a global pandemic, a time where celebration was set against the gloomy backdrop of universal, severe loss. With the long, painful year that was 2020 coming to a close, I thought that turning 20 years old would be a marker for better things to come: hope, healing, and peace. My birthday was instead marked by intense tragedy, bereavement, and grief. It started with a simple birthday wish FaceTime call from my Baba, my father.

I picked up my phone alone in my Philadelphia apartment. Baba awkwardly said happy birthday with an unusual somberness on his face: “Iman, I have not great news to tell you. There has been an accident.” My dear Muhammed Mamo, my mother’s younger brother, had disappeared into the depths of the Indus River rapids. Displaying ultimate altruism, he jumped in to save his children, my younger cousins, who had fallen in while taking a picture. My parents were to depart to Pakistan within the next couple of hours; I wouldn’t be home to see them off, to hug my mother goodbye, or grieve the presumed death of my uncle with my whole family unit. I hung up so Baba wouldn’t hear my yelps and cries; my roommate held me and stroked my back.

Surrounded by deep sadness, I slowly packed my things, repeating out loud, “I need shoes, I need shirts, I need …” to distract my brain from the severe anxiety and loneliness closing in on me. Returning to New York by train, I couldn’t stop the intense tears pouring down my face; I was coming back to a broken home, marked by grief and a lack of parental support. It was up to my siblings and me to navigate this new home life, one where our parents had no return date, and one where we were waiting for a verdict on my uncle’s life.

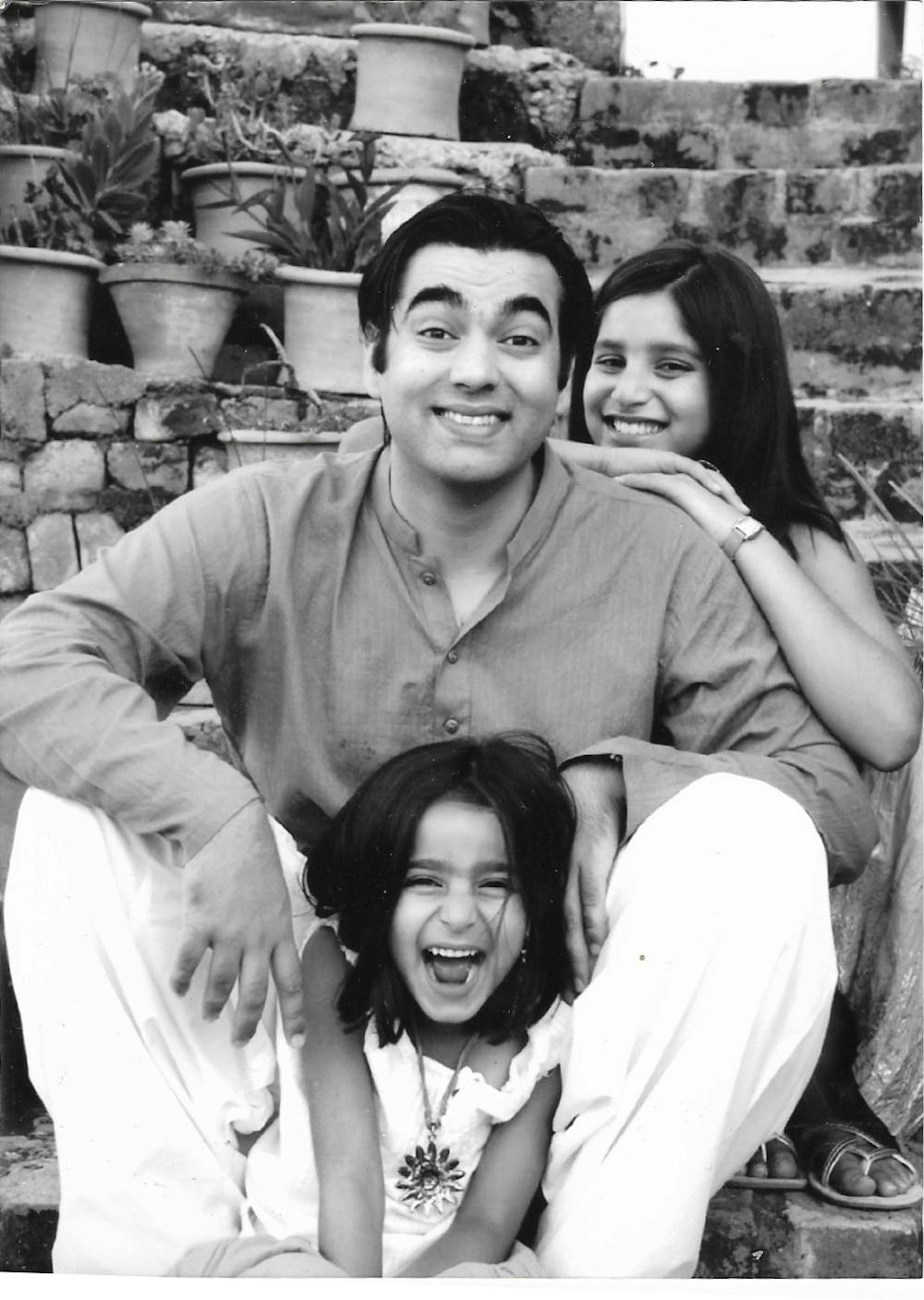

The last time I saw him was in December 2019 for a family wedding. His smile is still etched in my mind — so bright, just how he lived his life. A proclaimed extrovert, he was the life of any party. He had a fiery personality, and he lived his life with humor, laughter, and joy. He would tease me that I wanted to pursue history or international relations instead of a more “financially stable” field like medicine or engineering; he believed in me so much he thought I would be successful in any of those fields. He would be the first to the dance floor at any wedding and debated my dad on Pakistani politics. He was an avid cricket player and, most importantly, the best younger brother, son, husband, and father to his family. Muhammed Mamo is the most selfless person I’ve ever had the honor of knowing, displaying this most admirable trait up to his dying breath.

Grief is a complex emotion, affecting both the mental and physical health of the bearer. The days following his death and my return home, I fell into deep grief and depression; the circumstances became the elephant in the house, a shunned topic. I’ve experienced deaths in my family, but when someone so tragically and unexpectedly dies, and that’s compounded by the upheaval of my immediate family life, the grief is omnipresent. Sadness filled my house’s hallways. Empty chairs at the dinner table usually occupied by my parents were a constant reminder of the tragedy. My body was fighting a sickness of its own sadness. Days were spent crying over the loss, and my nights were occupied by the appearance of Muhammed Mamo in dreams of us drowning in the Indus together.

Friends would reach out and proclaim how strong I was; I questioned what it meant to be strong. I felt the exact opposite: I felt weak. Merely surviving became difficult. I was numb to everything. Nausea consumed my days. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t drink water. I couldn’t get out of bed. I could only mourn: mourn my uncle, mourn my family life, and mourn the self that once was.

Slowly, my interests dwindled, and an apathetic figure took the place of the old me. Suffering defined my identity. With no word about my uncle’s body, I was instead reminded of the times: 25 members of my family were diagnosed with COVID-19 from gathering together in light of the family tragedy — most were elderly or deemed high-risk. The mysterious virus lived in my dad, my grandmas, my aunts, my uncles, and my mother. I prematurely prepared, grieving the deaths of family members infected. What had my family done to deserve so much pain? What had I done to deserve this? I saw no light at the end of the tunnel.

These questions haunt me to this day. I became jealous of friends and peers who didn’t have to deal with this unbearable burden; they were so free, and I was trapped, closed in by depression. I believed no one understood my pain, my suffering, and my grief.

I remember having a phone call with a then-acquaintance in late November; I had to explain my family situation to her, so I could get out of a sorority commitment. After giving her the rundown, she interrupted me: “Iman, are you OK? Help me understand what you're feeling?” I broke down; it was an unexpected response. She barely knew me or my family history but her empathy and willingness to listen took me by surprise. I responded, “To be honest, I am not okay.”

When I returned to school for the second semester, I started experiencing PTSD. Small reminders from the time of the accident would trigger my trauma and spur intense flashbacks of grief leading to panic attacks. I avoided my bedroom — where months prior I heard the news — as much as I could. I hid the luggage case that I brought home initially. I folded the clothes I wore the semester prior in the back of my closet. I felt unsafe in my shelter. I couldn’t escape it; I would close my eyes and see my uncle’s face. I was awaiting the next tragedy. When will it come? What is going to happen? Can I survive? I wanted it to be over, to no longer feel this overbearing and destructive pain.

My uncle was eventually found by a fisherman last month; he found his way back to us, buried in my family cemetery in North Pakistan, resting at the feet of his grandfather. Six months after his death, the pain is still fresh and will be a deep wound to heal; I still think and cry about him every day. Drowning is an act of martyrdom under Islamic tradition. In times of omnipresent suffering, I draw from my Muhammed Mamo’s status as a martyr and his selflessness.

I realized I am not alone; we are connected in our loss. Loved ones of nearly 3 million people are grieving their deaths from COVID-19 worldwide. Communities around the United States grieve the deaths of Daunte Wright, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and the countless unjust police killings of Black people. My peers grieve the loss of a normal school year and the Penn we once knew. I grieve the loss of my uncle.

The path to collective healing begins with these three words: “Help me understand.” The burden becomes lighter; my family, my friends, and strangers help carry my pain. Empathy, understanding, and actively listening to each other will set us free. We have to radically accept our circumstances and identify our pain and suffering to start healing. This horrible event has happened — what can we do from here?

I asked myself this question recently. I was frustrated: I still felt broken inside. I needed a new way to connect with this pain. I picked up reading poetry from 13th-century Persia by Sufi poet Rumi. Rumi himself, having gone through immense losses of close advisors, wrote immensely about grief. After a particularly harsh flashback, when I felt extremely weak, I turned to this mourning poem: “Don’t run away from grief, o’ soul / Look for the remedy inside the pain / Because the rose came from the thorn / And the ruby came from a stone.”

We have to accept that the thorns of grief still prickle; the stone of the loss still crushes. We hope, though, as time moves on, that we will finally see the roses grow and the rubies glow. His pictures reside in our family room. His resemblance lives on my cousins’ faces. His love for my aunts, my mother, my grandmother, and my family occupy our hearts forever. Roses and rubies.

I recognize that even months later, I am still not myself. Until then, I remember the words that took me aback all those months ago: “Help me understand.” We recognize the fragility of life.

Be there for your friends. Extend a hand of empathy to your colleagues. Tell your family members you love them. Avoid inflicting hurt towards others. It is never too late to apologize and seek forgiveness in yourself and your actions. Be compassionate. Choose kindness. Thorns may cause wounds, but all wounds eventually become scars. One day, when they heal, the pain lessens. But the scars remind you: “I have survived.”

The roses will grow and the rubies will glow. With that, peace will find us.

IMAN SYED is a College sophomore studying international relations from Rye, N.Y. She is The Daily Pennsylvania’s newsletter editor. Her email is imansyed@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate

Most Read

Department of Education opens investigation into Penn over ‘inaccurate’ foreign donation disclosures

Former Penn swimmers applaud Department of Education ruling that Penn violated Title IX

‘A travesty’: Penn faculty, alumni express concern over proposed Fulbright scholarship funding cut

More Like This