College junior Diana Cruz watched in horror in Long Beach, Calif., as one by one, her family members got sicker and sicker with COVID-19. First, it was her sister, 23, who tested positive on Dec. 30, 2020 and lost her sense of taste. Then it was her mother, Maria Guadalupe Rodriguez, 63, who kept sleeping for longer and longer hours each day, until she could barely walk and eventually became comatose. Finally, her father, 65, and other sister, 27, fell ill.

Cruz went from pleading with her mother to go to the hospital to “pulling the plug” on her ventilator just days after she was declared brain dead on Jan. 14. Looking back, she can only wonder if her mother was covering up the severity of her illness to shield her from more emotional distress.

Cruz said she doesn’t know why she was spared from contracting the virus herself. In the final weeks leading up to her mother's passing, Cruz, a pre-medical student, said she watched her coursework play out in real life. As the youngest in her family, Cruz was thrust into caring for her ill family members — running around her house masked as she cooked meals, incessantly cleaned rooms, and brewed many batches of fresh tea for her family members.

Although Cruz's other family members eventually recovered, she said the loss of her mother made her feel helpless.

Thousands of miles from Penn’s campus, Cruz said she heard rumors of students throwing parties and disregarding social distancing, prompting feelings of helplessness and anger as she witnessed the detrimental impact of COVID-19 first-hand. She remains full of questions: How had her mother contracted COVID-19 when her family had been so careful with safety protocols, and why had the virus been able to wreak such havoc on her family?

One year after Penn evicted students from campus as COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization, The Daily Pennsylvanian sat down with members of the Penn community who lost family members and loved ones due to complications from the virus. All of them described how their outlook on life and the pandemic were upended in just a year. They expressed hope that their stories would send a resounding message to members of the Penn community who continue to disregard COVID-19 safety protocols.

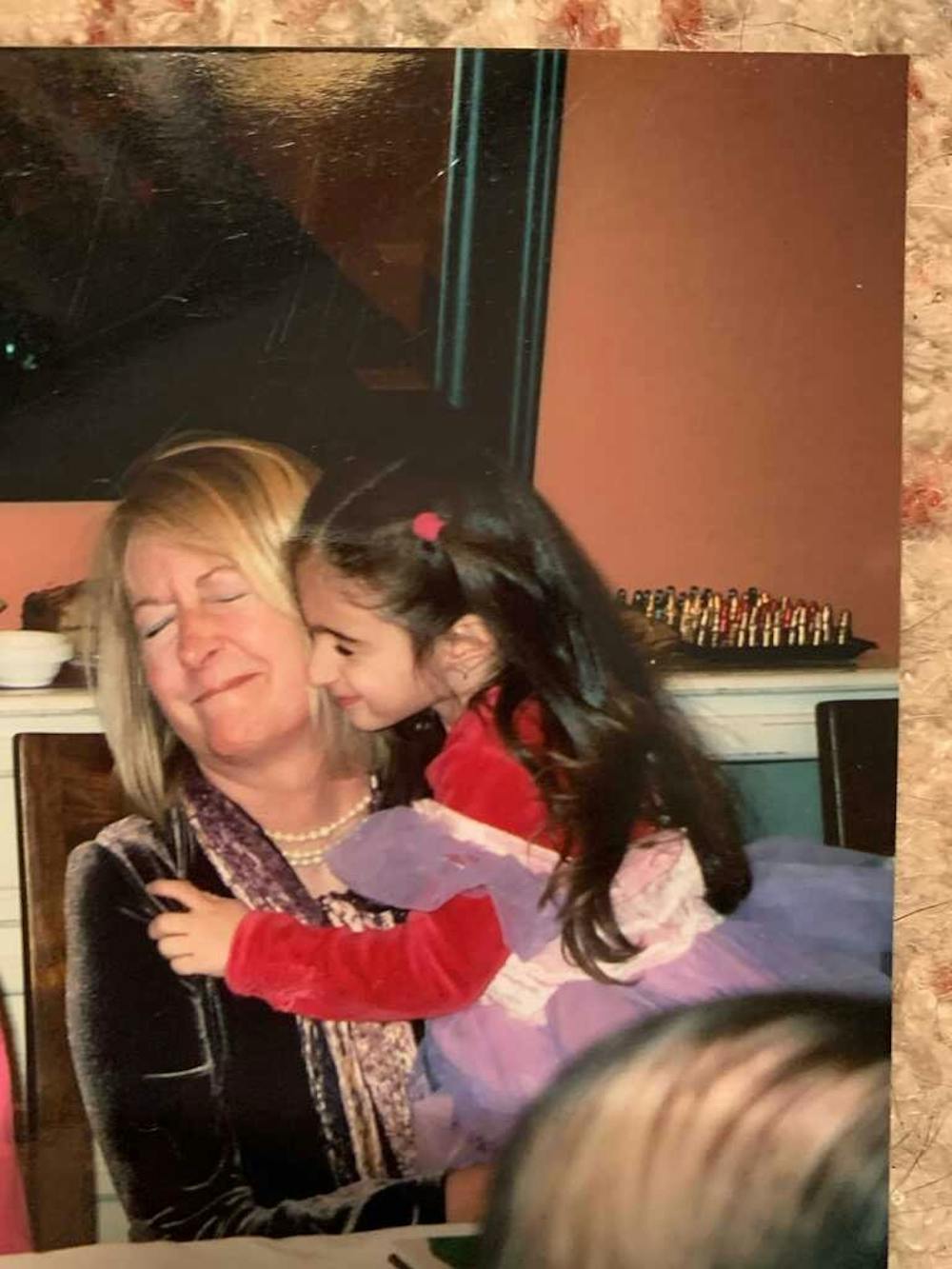

College junior Diana Cruz with her mother, Maria Guadalupe Rodriguez, who passed away from COVID-19 on Jan. 14. (Photo from Diana Cruz)

Saying Goodbye

Standing in a hospital corridor in May 2020, College junior Evan Rosario clutched a baby monitor in his hand and stared through the glass window at his grandmother, who lay still on her bed. It was time to say goodbye.

“I love you, grandma,” Rosario said to his grandmother, Cynthia Rosario, 73, in his last words to her. “I wish this wouldn’t have happened to you, but it’s okay for you to go. You can rest.”

It was almost midnight, and Rosario’s family had rushed to the hospital, piling into their car for the one-hour trip to Inspira Medical Center in New Jersey. Under the fluorescent hospital lighting, Rosario said that time moved slowly as the baby monitor was passed from family member to family member.

Almost a year later, the experience still haunts Rosario’s memory. Eight months after his grandmother died, his cousin Jeany Pope, 53, who worked as a nurse, also died of COVID-19 complications.

“There’s this emptiness that goes with me and it feels like I’m floating in space watching the world around me,” Rosario said.

College junior Evan Rosario with a photo of his grandmother, Cynthia Rosario, who passed away in May 2020. (Photo from Evan Rosario)

Students who lost family members to COVID-19 were often not given ample time or space to say goodbye to their loved ones, whether it was due to the quick-progressing nature of the illness or public health protocols intended to limit its spread.

Unlike Rosario, College sophomore Eva Faenza was never given the chance to say to say goodbye to her great aunt. Virginia Rossi, who went by Ginny, died of COVID-19 complications in December 2020. Visitors were not allowed into the hospice care facility, and her great aunt was so short of breath that having a conversation was impossible.

Faenza's great aunt was a cancer survivor, and only had three-quarters of a lung. Although she battled against COVID-19, she was eventually put into a hospice and died about a week later.

But Faenza said it did not become real for her until she arrived at the in-person funeral the next week, when she was surrounded by family members dressed in black.

A photo of college sophomore Eva Faenza with her great aunt Virginia Rossi, who passed away in Dec. 2020. (Photo from Eva Faenza)

Dealing with Grief

Faenza remembers the chilly, cloudy day in December when her family stood in a crowded cemetery in New Jersey, watching her great aunt’s wooden casket lined with red flares — her great aunt's favorite color — be lowered into the ground.

Once she stepped into the church, Faenza said she was overcome with emotion.

“I couldn’t control the crying," she recalled. "Even though we weren’t close, I think the circumstances of losing someone to the pandemic that probably wouldn't have died otherwise made me really upset.”

Faenza said she feels fortunate to have been able to attend the funeral in person. Funerals were prohibited in Philadelphia, so Faenza and her close circle of family traveled out of state for the service. For others, however, prohibitions on public gatherings have made it difficult for families to honor their loved ones at a funeral.

Senior Clinical Director of Counseling and Psychological Services Michal Saraf said the pandemic has dramatically altered the grieving process for students. Two major components of grief — the ability to say goodbye to a loved one and the means to engage in rituals surrounding death — are difficult, if not impossible, due to social distancing constraints, she said. While grief can look different for each person, she emphasized that mourning a loss is both healthy and important to moving forward.

“Mourning is not a mental illness," Saraf said. "Mourning is a normal part of human function.”

Rosario said he mourns the loss of his family members by absorbing himself in his work as a student and pharmacy technician at a local Rite Aid in his hometown of Middletown, Del. Rosario stayed home from Penn this semester to support his other grandmother who lived in an assisted living facility and support vaccine rollout efforts within his community.

“I wanted to find a job that gives meaning,” he said.

During his 20-hour workweek, Rosario said he feels lucky to help patients and his local community.

Still, the weight from the loss of his grandmother brings him down when he gets off from his workday, or shuts his laptop after completing coursework.

“There’s that creepy lost feeling that makes it tough when there is nothing going on,” Rosario said.

For students like Cruz, mourning is a balancing act of flipping between two worlds: home life and school work. She expressed gratitude for her pre-major advisor, who communicated her situation to her professors, and to her professors themselves, who gave her extensions on assignments and exams.

Saraf said that many students who use CAPS services have found their professors to be very accommodating when they face extenuating circumstances, and added that flexibility is essential for students dealing with difficult situations.

“Penn students, who tend to be really driven and hyper-focused on work, sometimes need to take a moment to breathe,” Saraf said. “Let's talk about what you need to honor this person and let's help you find room to do that in this strange world.”

Moving Forward

Months later, Cruz is still reminded of her mother on a daily basis. Cruz remains inspired by her perseverance; her mother left Mexico when she was 20 years old in search of a better life, hoping to be a nurse.

“That’s a big reason why I wanted to be pre-med. That’s something we shared — medicine and health,” Cruz said.

Oftentimes, though, the reminders take an emotional toll on her. Cruz said she struggled in her physiology class, BIOL 215: Vertebrate Physiology, when the professor was lecturing on the pulmonary system, which played a role in her mother's death.

“My mother passed because her lungs stopped, and so her heart stopped, so she no longer had blood flow to the brain. That was one of the first things we learned in class,” she said.

Faenza is also reminded of her great aunt’s death on a near-daily basis every time she sees students disregard COVID-19 safety on campus. She said that her great aunt's death served as a wake-up call.

“It became very real that I could potentially get really sick from COVID-19,” she said, hoping that other people will realize the same. “Losing a family member, or potentially infecting someone, is just not worth going out and partying every day.”

As deaths caused by COVID-19 deaths in the United States approach 540,000, Rosario implored students to consider the individual lives that were lost and the loved ones that were impacted.

“We should take a second to understand that everyone’s got a story,” Rosario said.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate