Women weren’t always a priority for Penn Athletics.

Long before the establishment of Title IX, women's athletics at Penn were minor. Looking back 100 years, female students at Penn weren’t even allowed to use campus gymnasiums.

Today, women’s athletics have come a long way due to years of progress — in great part due to the passing of Title IX.

Title IX, a federal civil rights law passed as part of the Education Amendments of 1972, was enacted June 23, 1972 and its interpretation was published in June 1974. The law was designed to prevent discrimination based on sex in educational programs or activities, including athletics.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program receiving federal financial assistance," Title IX states.

The civil rights law was rapidly linked to sports and inequity across schools in the nation and spurred controversy, especially at colleges and universities.

Before Title IX

Before Title IX, few opportunities for female athletes were available. Across the NCAA, athletic scholarships and championships were not available for women’s teams. In 1972, there were about 30,000 women compared to 170,000 men participating in NCAA sports.

The law mandated that women be given opportunities within athletics, including equal facilities, equipment, and scholarships. While Penn does not give out athletic scholarships, it was required to comply with the other components of the law or be subject to the loss of federal funding and potential prosecution.

To this day, Title IX does not mandate equal funding for men's and women's athletics, but ensures that they have equal access to quality resources such as locker rooms, medical treatment, training, coaching, practice facilities, tutoring, and recruitment.

Direct response to Title IX

Soon after Title IX began to be enforced, around October 1974, Penn's Athletics Director at the time, Fred Shabel, gave his thoughts on the law and assured that Penn had been making progress towards more equal opportunity, even before the law’s passage.

“Title IX is only verifying what we have been doing,” Shabel said.

It appeared that Penn was heading in the right direction towards ensuring that women’s athletics were on equal footing with the men.

By 1977, additional progress was made in women’s athletics at Penn, a large part of it credited to the arrival of new women’s Athletics Director Connie Van Housen. When Van Housen arrived, there were eight varsity women’s sports available, and shortly after, there were 12. Additionally, the coaching staff grew from less than five to about 20.

“We were ahead of the gun,” Van Housen said. "At that time it was about the largest [women's] program around.”

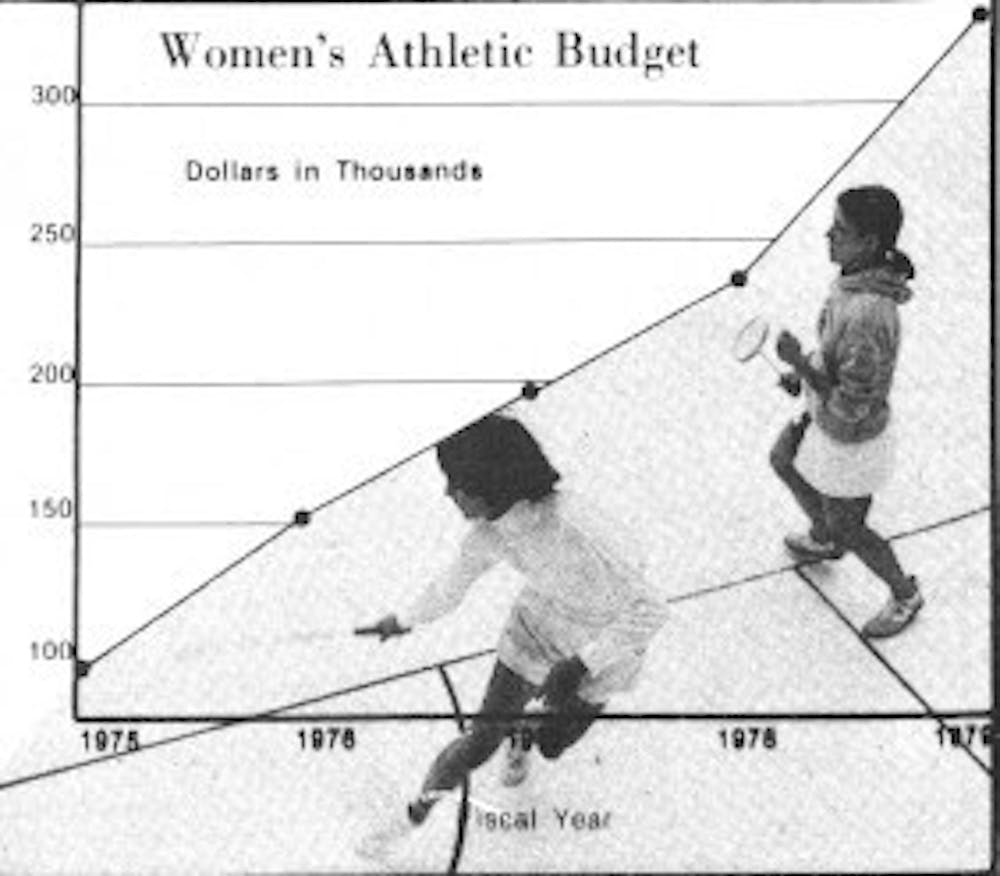

According to Van Housen, the women’s athletics budget had increased and the University Athletics Director Andy Geiger had been very supportive of women’s athletics. But not everything was great.

“[The] facilities are not equal between the men's and women's programs,” Van Housen said.

There were many things that were yet to be worked on by the University. First, Van Housen was concerned by the lack of media coverage from the newspaper.

“It’s difficult to generate attendance and interest without the exposure,” she said.

Additionally, under the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, recruiting was made difficult when compared to the NCAA. At the time, coaches were allowed to go to high school games but, unlike for men’s recruitment, they were not allowed to speak to athletes.

Another notable discrepancy was the fact that men and women’s coaches did not receive equal pay for similar job descriptions. To add on to that, women’s coaches were hired on salary rather than contractual basis.

Just as the progress seemed to be plateauing, the women’s track and field team was reported to be elevated to varsity status, marking Penn's 13th women’s varsity sport in 1978.

In 1979, Penn seemed to have found a loophole to get out of fully complying with Title IX.

“Title IX does not categorically eliminate inequalities — it simply eliminates sex-based reasons for those inequalities,” Linda Henry from the DP wrote.

Penn reasoned that the disparities in their spending per athlete — $1.01 million and $328.6 thousand for 856 men and 371 women, respectively — were not sex-based. Still, they blamed Title IX for having to cut back on popular men's sports such as basketball and others that brought in revenue.

“We’ve never denied the women anything they’ve submitted on their budget — men we’ve cut back on, but not women,” Reid Howard, the athletic business manager at the time, said.

In April 1979, possible threats to Title IX arose, and Van Housen along with other female athletic administrators mobilized support against them. Some of the proposed changes to the law included exempting athletics and revenue-producing sports from Title IX.

However, these worries dissipated after none of these changes were made to the law. However, a new provision under Title IX stated that “Sports scholarship money be distributed in proportion to the number of males and females enrolled.”

In 1984, the Supreme Court ruled that Title IX applied to programs receiving federal funds. This left lots of women with less federal funding under the impression that they didn't fall under the protection of the law.

“Institutions did not favor women until they were required by federal law, including Penn.” Penn Women’s Center director Carol Tracy stated. “I'm concerned with the Supreme Court ruling there will be more backsliding.”

Athletes weren't worried about backsliding of women's athletics at Penn, but inequalities still existed in the program. For example, women didn’t have the same opportunities to travel as men, because it was not included in their budget. Some athletes also pointed out that the administration was more lenient with men’s teams. Men’s sports also had a larger recruitment budget. Even though some teams received the same equipment and practice time, fans, alumni, and administrative reports revealed a preference for the men’s programs.

“While administrative support and money increased for her team, the women still [lagged] behind the men in their pull in admissions, budget, coach salaries and publicity,” the DP wrote on Apr. 16, 1984.

20 years after

In the 1990s, the enforcement behind Title IX was faltering, and its application was unclear.

“There are more questions than answers about what it means to have gender equity in your program as well as to be in compliance with Title IX,” Carolyn Schlie Femovich, from Penn's Athletics Department, said.

Femovich hoped that the University would take steps to assess their compliance with Title IX. They had already changed the structure of their Athletics Department to what Femovich termed a “sex-blind administration.” Before this switch, men's and women’s sports were administered separately.

In June 1994, the non-profit feminist legal advocacy group, the Women’s Law Project of Philadelphia, filed a lawsuit on behalf of 10 Penn coaches and female athletes against the University claiming that they were in violation of Title IX. According to the federal civil rights complaint, the University discriminated against their female athletes by not giving them the same equipment and services that were provided to male athletes.

According to Penn women’s crew coach Carol Bower, the coaches had already written a letter to the Athletic Department demanding specific improvements and the creation of a task force to continue making further recommendations.

“In many instances, there are significant disparities in the quality, amount, suitability and availability of equipment and supplies [including uniforms and practice gear] provided to women and men athletes,” the complaint states.

The complaint asks the University to upgrade women’s volleyball and field hockey to level one status so that they would have increased resources. Additionally, they requested that on-site trainers be hired and salary claims be resolved. When the University didn’t respond by the deadline, they filed a complaint against them.

In July, the recently-arrived Athletics Director Steve Bilsky indicated a willingness to negotiate in an effort to avoid further investigation. The University committed $500,000 to gender equity issues over the next two years as a result of the inequities that the University itself exposed in their gender-equity report.

The University’s ongoing cooperation appeared to be enough to avoid a long trial similar to the one Brown University had just experienced. Sure enough, in September 1995, there was a settlement between Penn and the Women’s Law Project.

Under the terms of the agreement, the crew team’s boathouse would be renovated, and they would receive additional boats and movable storage racks. The women’s teams also received weight room renovations, a weight trainer for female athletes, and many assistant coaches were upgraded to full-time positions. The financial terms of the agreement were not released, however Bilsky assured that no funding was removed from men’s teams.

There was still a huge discrepancy between male and female athletics. For example, there were disparities between their facilities, women’s teams still did not all have full-time assistant coaches, and they drove to games in vans driven by coaches instead of buses driven by chauffeurs like the men.

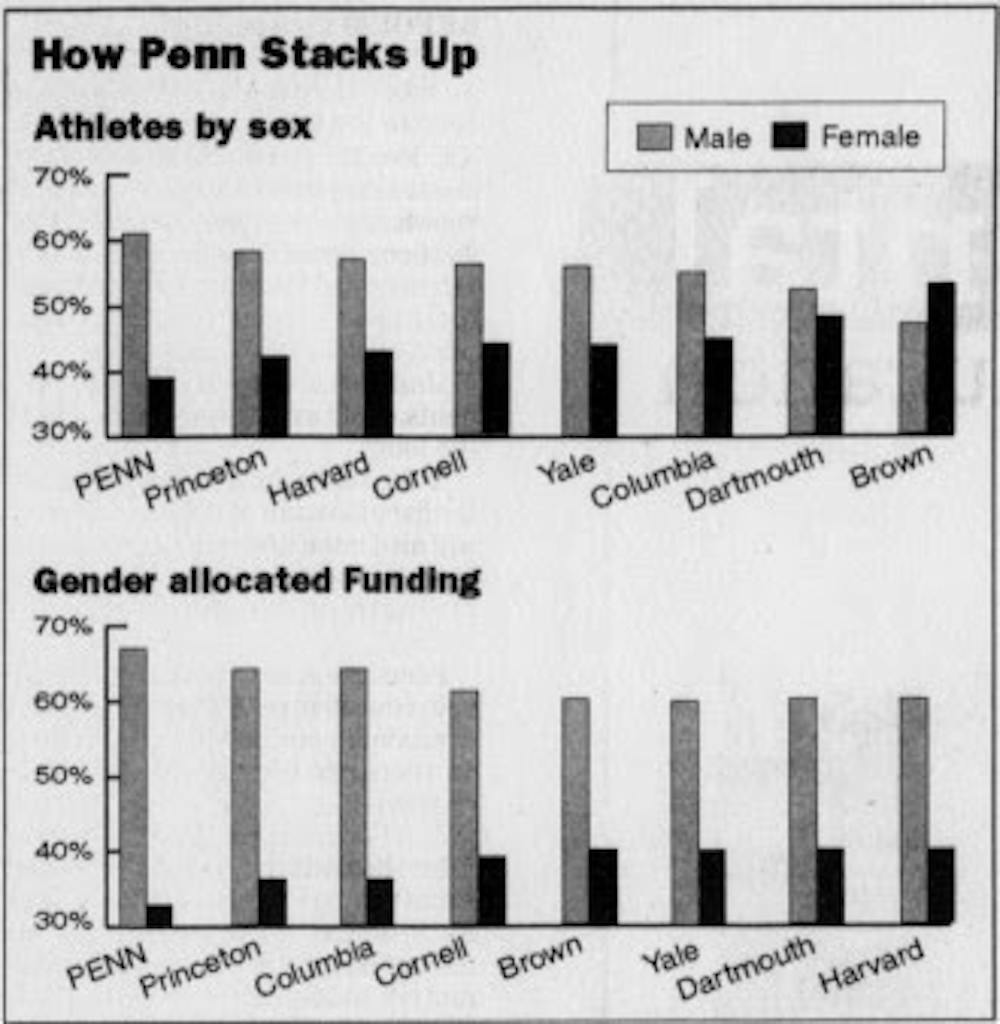

In 1999, the University’s budget showed that men’s athletics received twice the money than women’s did — $3.6 million and $1.8 million, respectively. Penn also suffered from a huge disparity in the proportionality of students in men's sports and in women's sports. They had the biggest discrepancies in the Ivy League.

Now

The discrepancies haven’t been completely resolved. Today, Penn has one more men’s varsity team than women's teams — 16 and 15, respectively.

According to the most recent data from the Department of Education for the Equity in Athletics Data Analysis in 2018, the University’s total expenses on athletics are approximately $44.2 million. Of those that were allocated to men's and women’s teams, approximately $11.5 million were allocated to men and $6.3 million were allocated to women. This means that of the allocated expenses, men received approximately 65%, compared to 35% by women.

This is, however, in tune with the proportion of athletes playing. Without double-counting for athletes playing multiple sports, the University has 524 male and 349 female athletes. This aligns more closely with the allocated funding for each sex, rounding out to approximately 60% for the men and and 40% for the women.

There have even been improvements to coaches' salaries, however there is still a discrepancy between salaries for coaches on men’s teams and coaches on women’s teams. For example, women’s teams head coach's average salary is $101,398, while in contrast, men’s teams head coach's average salary is $141,111.

Clearly, Title IX had a great impact on Penn's women’s athletics program and the Athletics Department as a whole, but like everything, there is always room for improvement.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate

Most Read

More Like This