Reflecting on the harrowing events of the Jan. 6 insurrection brings to mind how Benito Mussolini came to power as the Italian prime minister in 1922. As we shall see, there are many parallels between what happened in Italy 99 years ago and in Washington on Jan. 6, which show us just how fragile democracy really is.

Throughout 1921 and 1922 Mussolini, leader of the Fascist Party, vowed he would come to power. Italy in 1922 was a country still healing from war, economic crisis, and severe political strife, with an aggrieved lower-middle class who felt abandoned by the political class and was on the verge of being disenfranchised.

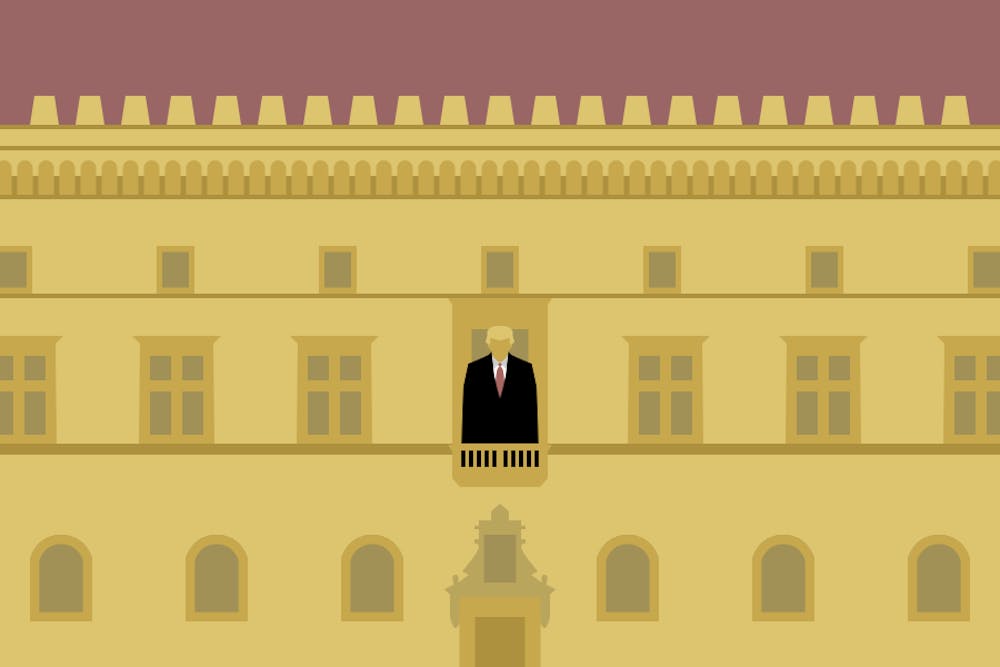

At a rally in Naples, Mussolini declared from the podium, “Either the government will be given to us, or we will seize it by marching on Rome.” Most of the moderate right-wing and centrist politicians, supported by several of Italy’s foremost business leaders, were ready to give Mussolini the benefit of the doubt, under the illusion that the whole movement would eventually deflate itself when confronted by the realities of governing.

Similarly, when former President Donald Trump announced his candidacy in 2015, the mainstream Republican leadership initially dismissed him as a crank. Then, on becoming the official GOP nominee, the common opinion was that the realities of the office would soon tame him. Instead, the truth was that, as told in Bob Woodward’s “Rage,” Trump had “hijacked” the Republican Party. The Republican base obediently followed Trump because his notions best reflected the grievances of the alienated or — more accurately — those who feared becoming overwhelmed by minority communities. The moderate and more centrist elements of the GOP, including the business lobbies, fell in line with him to guarantee their political future.

When Trump sensed in the last stages of the 2020 campaign that the result would be close, or even that he could lose, he convinced the GOP base and leaders, through a drumbeat of lies and conspiracy nonsense, that the election was “rigged.” It allowed Trump to foment the Jan. 6 attempted coup at the now infamous rally on the Ellipse. Trump’s remarks on that occasion bear an eerie similarity to Mussolini’s speech in Naples on Oct. 24, 1922.

Political power was the key to both speeches. Trump wanted to keep it; Mussolini wanted to win it. The fact that Trump then chose to return to the White House while the insurrection played out on Capitol Hill parallels Mussolini’s decision to return to his base in Milan rather than personally lead his followers (the “Blackshirts”) into Rome. Both men advocated for illegal actions but thought they could dodge the consequences by staying away from the actual fray.

The results of Mussolini’s march were tragic. The Italian king, threatened by about 25,000 Blackshirts storming Rome, named Mussolini prime minister. Mussolini’s contempt for democratic norms would ultimately bring about the abolishment of elections, as well as the shameful Racial Laws of 1938 and 1939, depriving all Italian Jews of their rights. Had the invasion of the United States Capitol succeeded, something similar could have happened in the United States: Trump remaining in office, backed by an obedient, well-funded GOP composed of cowed moderates and myth-fed, extremist firebrands.

Neither Trump nor Mussolini really considered elections to be the decisive factor in determining political power in a democracy. Trump’s conversation with Georgia’s secretary of state, when he asked him “to find” 11,780 votes, reflects the former president’s contempt for democracy’s basic instrument. Trump and Mussolini instead considered rallies to be the true measure of their political strength, so much so that the flop of a rally in Tulsa last June caused Trump to immediately reassign his campaign's chief operating officer.

Of course, the situations in the United States this year and in Italy 99 years ago also present profound differences, as reflected by their different outcomes: Trump failed and was immediately impeached for “incitement of insurrection,” while Mussolini’s insurrection succeeded. In 1945, however, Mussolini was arrested and immediately executed (without trial).

Though I graduated in 1969 — a year after Trump — from the College, I do not know Trump. I do know, though, that he was not on the Wharton dean’s list in 1968, and that the lectures by the Economics professor we shared, Lawrence Klein (the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1980), had absolutely no effect on him — if his later decisions on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, NAFTA, tariff wars, and the emasculation of the World Trade Organization dispute are anything to go by.

As far as I remember, Trump never participated in any of the civic activities that most involved the student body at the time: the Vietnam war, Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, voting rights, the 1968 election campaign, or even the movement to stop University administration from cutting down a number of trees in the Quadrangle.

As unfortunate as it may sound, I don’t believe there is much the University can do to distance itself from Trump and his family. There are no major buildings or other structures named after him which could be renamed. Penn also cannot legally publish his senior thesis (if he had one) or his transcript without his consent. My only advice — however unsatisfying — is to ignore him and allow his memory to gradually fade away, depriving him of the attention he so desperately wants.

GIOVANNI MANFREDI is a 1969 College graduate now living in Muscat, Oman. He served as the Italian Ambassador for Disarmament at the United Nations and his email is nannimanfredi@gmail.com.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate