When people refer to the “good old days,” they usually refer to something that’s a bit more hardcore and dangerous. Well, those traits are steeped in the legacy of one of Penn’s oldest traditions, the Rowbottom.

From the early 1910s until the late 1970s, the cry of “Yea, Rowbottom!” meant that chaos was underway, causing mass mayhem in the process. Students would do a number of objectionable things in the process, such as throw objects at windows, jump on vehicles, and even commit arson. Rowbottoms would happen most commonly around Penn sporting events such as football, basketball, and crew, as well as when warm weather arrived after a long period of cold weather.

The origin of Rowbottoms have been disputed over the years, but all roads tie back to Joseph T. Rowbottom, who was a student at Penn in the year 1910. Holly Rowbottom, his granddaughter, attempted to set the record straight in 1973.

“The true story, as passed on to me by my father, is this: There was this classmate of my grandfather who lived in a room across the quadrangle,” Holly Rowbottom wrote in a letter to the Pennsylvania Gazette. “For some reason or other, this fellow never got his assignments straight. And, with a light usually on in Rowbottom’s room to all hours, he knew where he could get his information without fail. He would throw up his window and yell across the quad those now-famous words: ‘Yea Rowbottom!’”

What followed the benign interactions between Rowbottom and his classmate only pushed further what Rowbottoms became. After it became somewhat of a trend, Penn's football team called for Rowbottom after a team banquet, waking up everyone in the dorms in the process. In response, the angry, woken-up students began to toss the items they had in their dorms, such as garbage cans, pitchers, and anything else they could get their hands on. When this occurred, it marked the first ever Rowbottom.

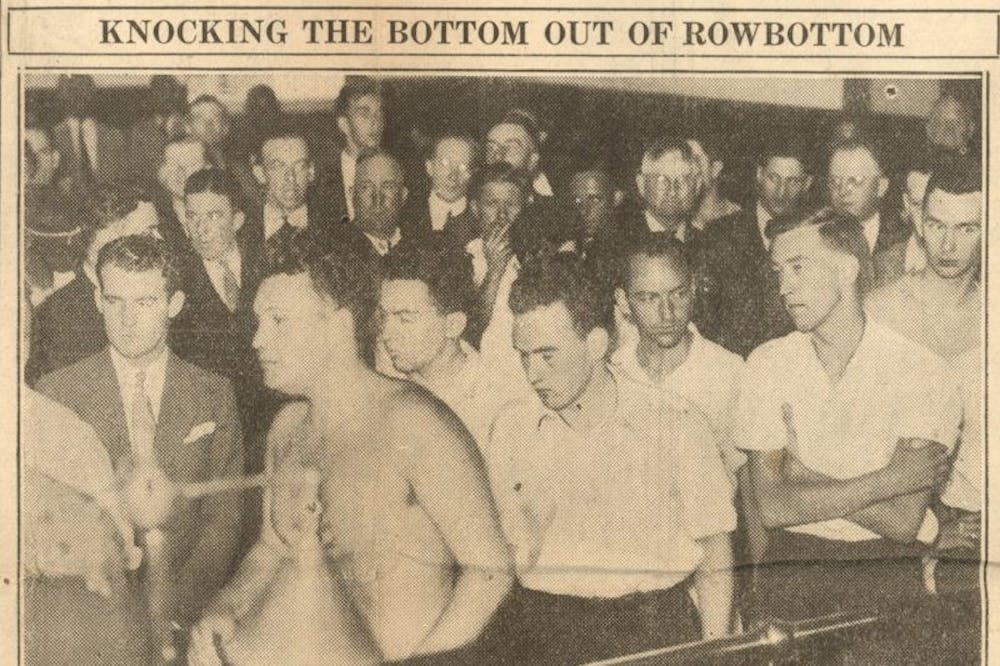

The occurrences of Rowbottoms persisted, but it took 18 years for the next documented Rowbottom to take place. On March 20, 1928, Penn men’s basketball defeated Princeton to become Intercollegiate League Champions, which prompted Penn students to riot once the game had ended and the police had left.

“A crowd of about 1,000 students set fire to trolley wires, pulled trolley poles from overhead wires, and lit bonfires in front of Psi Upsilon Fraternity,” Penn University Archives & Record Center wrote. “When firemen arrived, different groups of students carried off the fire hose, made away with a large red Philadelphia Rapid Transit automobile trailer, and changed the workings of the ‘automatic traffic semaphore.’ Seventeen students were arrested on a charge of inciting a riot.”

After that Rowbottom and one that happened two months later, the event occurred more than once almost every year until 1971. What ensued during a Rowbottom truly cannot be understated: windows would get smashed, cars would get overturned, and in the 1940s, panty raids became a staple of an average Rowbottom.

In small doses, the police were able to handle the situation, but when a Rowbottom became exceedingly large, they would get overwhelmed and left without a way to maintain any semblance of order.

Typically, only a handful or, at most 20-30 students, would get arrested as a result of a Rowbottom, but sometimes they would get so large that hundreds of students would get arrested. While arrests did occur, the charges would typically be quickly dropped. The most students that got arrested after a Rowbottom was 300, which happened in 1930.

Around this time, Penn began to adjust its policy on Rowbottoms and what its role was as the university they happened under.

“In the first decades of Rowbottoms, the University administration’s role was to show up at the police station to get charges dropped and to bail out students,” Penn University Archives & Record Center wrote. “But starting in the 1930s, as Rowbottoms escalated, the University began to be more concerned about both the damage and the University’s reputation. The University administration began publicly to express regrets and to apologize for the actions of students, and then to form investigative committees after each major incident of student rioting.”

The condemnation of Rowbottoms by Penn progressed to the point that, in 1940, Provost Thomas S. Gates declared a ban on the practice. Despite this, Rowbottoms continued to happen until the 1970s.

In 1971, the last documented Rowbottom until 1977 occurred, which happened to be the first female-led Rowbottom. Two students managed to round up around 40 other women who stormed into the Quad at 12:30 a.m., where plenty of men appeared at McClelland Hall to greet them. It was broken up quickly, and it initiated a seeming moratorium on the practice.

Then, in 1977, the Academy Award for Best Picture was a contest between Network and the Philly-based Rocky. After Rocky won the Oscar, around 1,500 students gathered in the lower courtyard of the Quad, where they proceeded to attack Hill House and initiate a sit-in on Spruce Street.

After one final freshman Rowbottom in 1980, the practice was completely put to rest. Rowbottoms have since become a thing of the past, something that old alums might refer to in a wistful manner to remember a time much different than now.

Their impact on Penn’s campus culture at the time, though, was as massive as it was chaotic.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate