In the spring of 2018, I attended a school assembly where I listened to Rachel Swarns, a New York Times correspondent, explain our high school’s tie to slavery. I was a sophomore at Georgetown Preparatory School, which was the same institution as Georgetown College (now University) when it sold 272 enslaved people to save its plantation from bankruptcy in 1838. I’ve always taken pride in my school’s 220-year history. But never had I been aware of this troubling past until Swarns’ investigation sparked national debate.

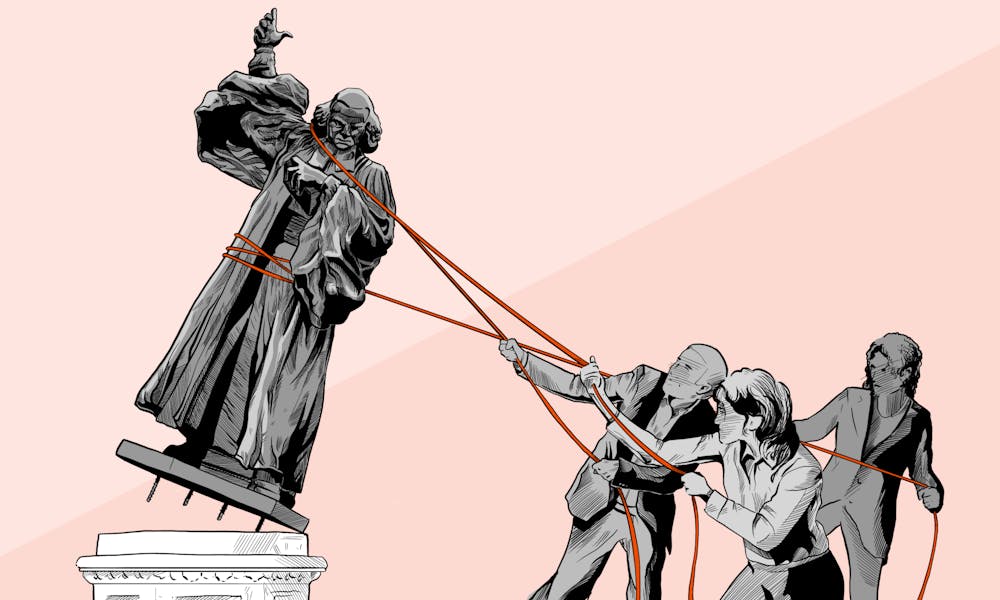

This year, many colleges were forced to reckon with their racist past as Black Lives Matter protests gained momentum. At the forefront of this reckoning are the statues falling across the country, from the Confederate statue at the University of Mississippi to the Howitzer Monument on the campus of Virginia Commonwealth University. On July 2, Penn announced plans to remove the statue of George Whitefield, given that Whitefield “prominently advocated for slavery.”

The scrutiny that statues attract raises questions about the purpose of statues and why they are so powerful. My answer is that statues reflect values of the time in which they were erected. And since they are displayed in public spaces, they solidify and perpetuate these ideals. The 16-foot-tall Brick House sculpture that Penn installed at 34th and Walnut Streets gateway last week, for example, is a socially situated icon meant to celebrate Black feminism and inclusivity. That its installment coincided with the election of America’s first Black female vice-president elect makes this message all the more powerful.

But the values considered virtuous in one era can be rejected in another, hence the debates over whether great figures with tarnished records merit statues. Such debates fit George Whitefield and Benjamin Franklin, two prominent figures associated with Penn.

Some activists have called for toppling all controversial statues, which they believe would set the stage for achieving racial equity. But I think a blanket removal is profoundly misleading for two reasons.

The first is that removal fails to do justice to some historical figures, who are complex characters that can’t be pigeonholed into good guys and villains. Consider Ben Franklin, our founding father. Franklin signed the Declaration of Independence and secured the Treaty of Alliance between America and France. However, he also owned slaves for part of his life, admirably becoming an abolitionist later on. Franklin’s record contains both positives and negatives. However, for all of his moral flaws, his positive contributions to both America and Penn earn him a place on Penn’s campus.

The case of Whitefield is trickier. A preacher who cared deeply for orphans and Black converts, Whitefield nonetheless advocated legalizing slavery in Georgia. He had slaves working on his plantations, but used the money to fund his Bethesda orphanage. Whether or not he merits a statue should have been up for debate not between President Gutmann and Provost Pritchett, but among all concerned Penn students who should decide for themselves if Whitefield’s contributions are subordinate to his faults. In their announcement of Whitefield's removal, the president and provost absolved Franklin for “chang[ing] course in his life.” Unfortunately, Whitefield was beneficiary of no such nuanced thinking.

The second reason why removing statues is misleading is that we need statues to remind ourselves of history. Take Germany, which has to cope with the dark legacies of the Holocaust and imperialism in Africa. The Germans decided that, if statues represent values, they should be preserved and re-interpreted rather than hidden. Beginning in the 1990s, Bremen, Nuremberg, Düsseldorf and other cities began turning statues of colonists into “anticolonial memorials” adorned with new plaques dedicated to the victims of German colonialism. In 2004, Hamburg re-exhibited the statue of Hermann Wissmann, governor of the German East Africa colony, which had been stored in a warehouse for decades, along with a reflection room where visitors could discuss Germany’s neglected colonial past. Germany’s case shows that troublesome statues, when reinterpreted, can be educational. Their presence in public spaces puncture everyday indifference and forces people to rethink their history.

Following this guideline, Ben Franklin’s statue should be relabeled “slaveholder” and “abolitionist,” as columnist Emily Chang has suggested. The Whitefield statue could have served an educational purpose had Penn not decided to take it down. To be clear, I don’t mean to defend Whitefield’s involvement in slavery, nor do I think his statue should be brought back. But since our history curriculum has selectively left out Whitefield’s role in promoting slavery, it would be more edifying if Penn reinvented his statue to educate students rather than pulling it down entirely. A revamped Whitefield statue, paired with the new Brick House, would powerfully attest to Penn’s commitment to inclusion and instill this value into students’ consciousness. Removing Whitefield is a symbolic break with our racist past, but doing so better serves our complacent self-exoneration than raising awareness on negative aspects of our history.

BRUCE SHEN is a College first-year student from Shanghai, China studying German Studies. His email address is xshen01@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate