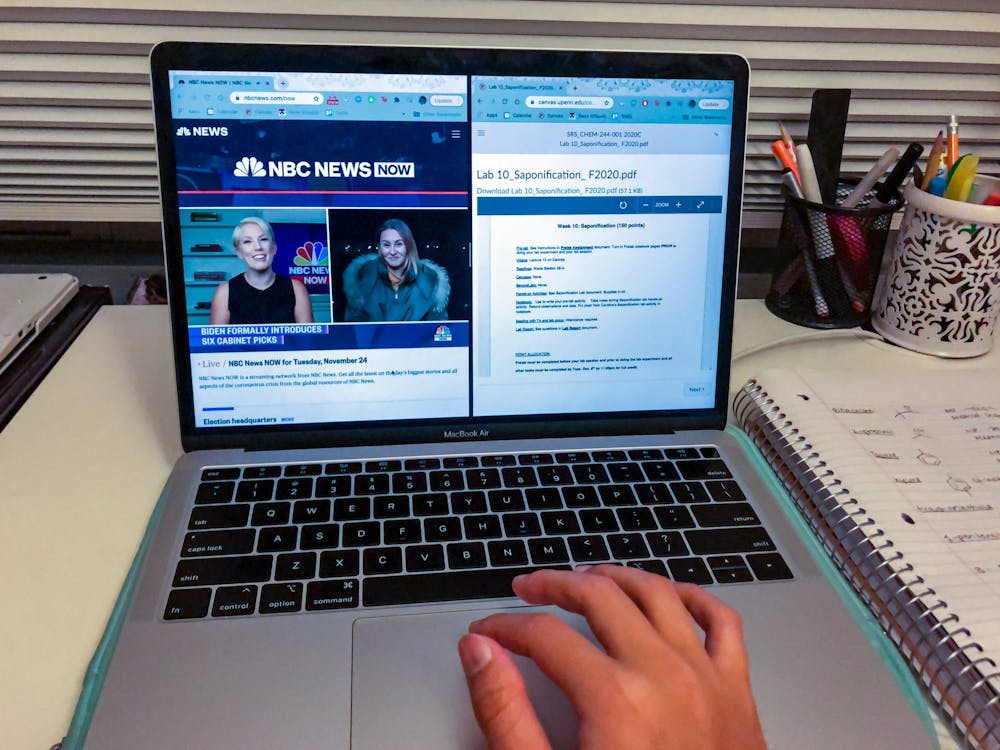

Did anyone pay attention in class during election week? If so, I’m dying to know how you did it. Sure, the Zoom tab for my physics lecture was front-and-center on my laptop, but I was really looking at The New York Times' Electoral College map on my second monitor. And listening to CNN from my TV. And scrolling through FiveThirtyEight’s live updates on my phone, for good measure.

I suspect that many Penn students were as obsessed with election week as I was, and the data agrees. According to a Penn Leads the Vote study covered in the DP, the 2020 elections had a considerable impact on students’ mental health. Both students and professors reported that the uncertainty following Election Day made it difficult to focus on their academics. Perhaps most concerning, some students lost significant amounts of sleep and had problems eating. Clearly, news coverage has an impact on mental health, and we need to do something about it. But this is far from a new discovery.

Before 1991, constant news coverage was extremely uncommon. But during the First Gulf War, CNN’s around the clock reporting provided instant updates that no other network could match. From then on, other networks adapted the 24-hour news cycle model. Following the 9/11 attacks, researchers found that the prevalence of PTSD was associated with the hours that one spent watching relevant news coverage and graphic events on television. Since then, constant news coverage has only grown more pervasive. 45% of 18 to 24-year-olds first interact with news in the morning via smartphone. I imagine that a significant portion of those surveyed didn’t even get out of bed before scrolling through the news.

Today, we are living in a world where information travels faster and in greater amounts than ever before. We benefit enormously from it: without these advances, we would be unable to host Zoom lectures or instantly message friends halfway across the world. But these improvements come with consequences, especially in how we receive and process information.

For instance, disinformation has grown at unprecedented rates. When anyone can post anything at any time, fact-checking is nearly impossible. In the networks that we have constructed, namely Twitter, fake news travels six times faster than real news. Simply by reporting on disinformation so often, mainstream news networks inadvertently transmit and amplify it. The immediacy and frequency of current news can also contribute to the firehose of falsehood propaganda model.

24/7 news coverage has also dramatically increased competition among networks. This can be a good thing, but it can also lead down a slippery slope. In their desire to attract viewers, many networks won’t give their audience objective information, but the opinions and commentary that they want to hear.

For decades, America had upheld a tradition of objective news. But now, this objectivity is subjective. Opinion news grabs the attention of more viewers than neutral reporting does, becoming more popular as news companies compete for viewership. On many news networks, there is more commentary than news-gathering. When arguing is a constant on many news networks, it’s no surprise that polarization has increased dramatically in recent years. As Gen-Z university students, we have grown up constantly surrounded by information and opinion. We aren’t the primary consumers of news yet, but we soon will be. And we can do better.

While we can’t demand massive change in our news quite yet, we can improve on our own actions. Although it’s difficult to look away when there’s a breaking news story, it can be helpful to take a step back and think. How will it help me, or anyone else, to refresh the live updates to this story? How is reading now any different from reading later, when the facts have settled?

Paradoxically, another way to beat news addiction is to read more news, as long as it comes from varied and objective sources. For instance, reading international and local sources—which also tend to be less biased—broadens one’s perspective and is reminiscent of reading through an old-fashioned newspaper, parsing through each section of news instead of indulging in an infinite supply of just one kind of article.

It’s difficult enough for Penn students to be productive from home, and the struggle is only worsened by recent election anxiety and ongoing pandemic loneliness and uncertainty. Unfortunately, news providers are not on our side. Our stress, fear, and anger grow news providers' business, and their constant streams of articles continue to evoke these responses in us, fueling a vicious cycle. If we don’t make a conscious effort to break out of it, we only hurt ourselves in the long run.

CAROLINE MAGDOLEN is a College and Engineering first-year student studying Systems Engineering & Environmental Science. Her email address is magdolen@sas.upenn.edu

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate