With the Food and Drug Administration’s recent announcement that it might authorize a vaccine for emergency use before Election Day, some experts are comparing Operation Warp Speed – the United States' coronavirus vaccine effort – to the 1976 swine flu vaccine disaster, where the government quickly released a vaccine to the public that caused serious side effects in some recipients. But vaccine inventors from the Perelman School of Medicine say making the comparison is not that simple because the conditions in both scenarios are very different.

On August 30, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn announced he might authorize a vaccine for emergency use ahead of Election Day and before vaccine testing trials are complete. Critics fear that authorizing a vaccine in October could be politically motivated, as an attempt by President Trump's campaign to increase his popularity ahead of the election. But the president, a 1968 Wharton graduate, has denied such claims. Some critics have drawn comparisons between Trump's Operation Warp Speed and the Ford administration’s hastily-made 1976 swine flu vaccine that caused Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare neurological disorder, in 450 people.

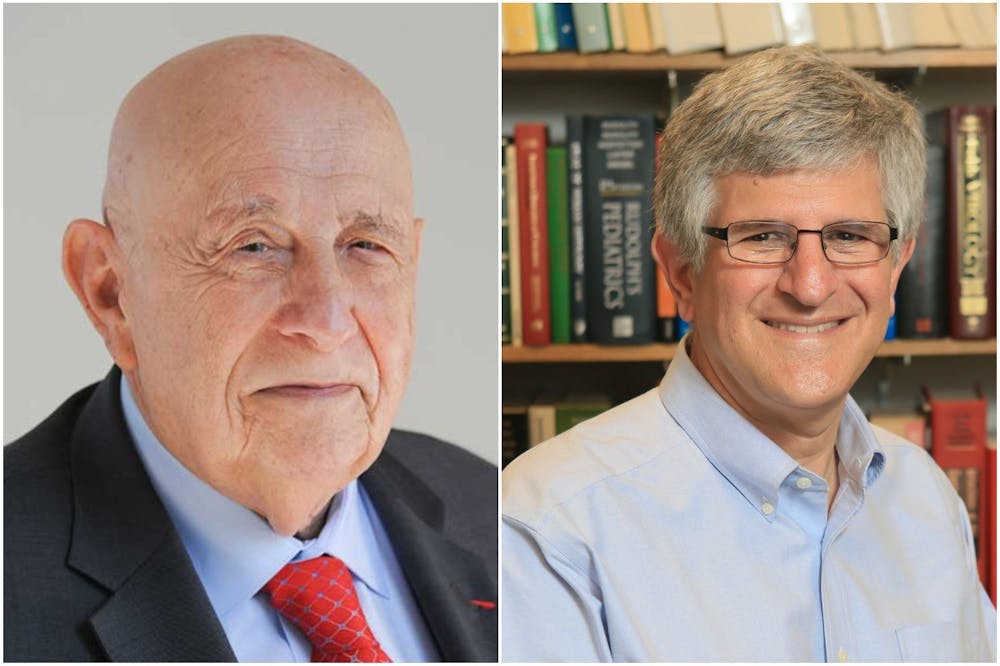

But Penn Med emeritus professor of pediatrics and inventor of the rubella vaccine, Dr. Stanley Plotkin does not think the comparison between the current pandemic and the 1976 swine flu outbreak should be made, as the circumstances surrounding the two outbreaks are very different.

“The [1976] swine flu vaccine was not so much a problem of a harmful vaccine, but one that turned out not to be needed,” he said.

When an outbreak of H1N1 broke out at Fort Dix military base in New Jersey in 1976, scientists speculated that the strain could be similar to the 1918 swine flu that caused a global pandemic. To try to prevent an epidemic, the Ford administration sidestepped World Health Organization regulations to fast-track and launch a massive nationwide vaccine campaign.

What the Ford administration did not anticipate was that the swine flu never spread far beyond Fort Dix, making the vaccine unnecessary. Four hundred fifty of the 45 million people vaccinated developed Guillain-Barré syndrome, and the cases attracted national attention. In an election year, the general public saw Ford's vaccine campaign as a harmful publicity stunt, and distrust of his administration grew.

Maurice R. Hilleman Chair of Vaccinology at Penn Med and co-inventor of the rotavirus vaccine, Dr. Paul Offit received the 1976 swine flu vaccine and did not suffer any major complications. Like Plotkin, Offit said the United States’ high COVID-19 death toll makes the current pandemic very different from the 1976 outbreak.

"In retrospect, now we know that [the 1976 swine flu] wasn't a problem," Offit said. "But [COVID-19] is a pandemic. We have 181,000 people dying in this country, and I'm not sure it's quite analogous."

The New York Times reports that at as of Tuesday evening, at least 189,500 Americans have died of the coronavirus, and more than 6,344,700 have been infected.

In order to earn a license for widespread use, vaccines typically undergo three phases of placebo-controlled testing. Each phase includes more participants and costs significantly more than the last. Offit said that high financial risk typically prolongs the process of earning approval for each phase.

“What's happened [with the COVID-19 vaccine] is that the government is essentially taking the risk out of it,” Offit said. “The government or the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation or the World Health Organization have put tens of billions of dollars into these vaccines and said, ‘We'll pay for the Phase 3 trials. We'll pay for the mass production. You won't have to take that risk.’”

Offit said the COVID-19 vaccine development process is expedited by the fact that so many companies around the world are trying to produce a vaccine at once. In contrast to the 25 years it took him and his fellow researchers to develop the RotaTeq vaccine, Offit tentatively predicts that a COVID-19 vaccine could be released in early 2021. However, he said this isn’t a firm estimate, due to the unpredictable nature of the virus.

“Vaccine developers are conscious of the fact that this is not easy,” Plotkin said. "That this is a virus that affects us in a different way than many of the diseases, many of the agents, for which we do have vaccines.”

Authorizing a COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use before Election Day would require administering doses before Phase 3 trials are finished. Emergency use authorization is not the same thing as full vaccine licensure, which is more regulated and can take years to obtain.

According to Offit, releasing vaccines before completion of Phase 3 is rare, but not unheard of.

Since many COVID-19 vaccines are being administered in two doses, an early release could come before both doses are administered to all participants in Phase 3 trials. Offit said prematurely releasing a vaccine would increase the risk of researchers not observing certain rare complications before the vaccine is used in the general public.

Even if one COVID-19 vaccine is selected for emergency use authorization, there will likely be multiple companies’ vaccines in circulation at once before a select few emerge as frontrunners over time.

“What I look forward to is multiple different kinds of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 [being released],” Plotkin said. “And we won't know for a while which one is best, if there are differences between the vaccines.”

Offit said he won’t take any COVID-19 vaccine until he has seen the data from the trials’ results. When vaccines are released, Offit advises Americans to check the Phase 3 trials’ sample sizes and rates of protection and complications among their own age groups and among people with similar medical conditions to their own.

"I’m not going to get a theoretical COVID-19 vaccine," Offit said. "Let me wait and see what the vaccine actually looks like. Has it been tested in my age group? Has it been tested in people that have certain comorbidities? What are the data? To what extent do we know it’s safe? To what extent do we know it’s effective? How long do we know it’s effective for?”

Plotkin feels safe to take a COVID-19 vaccine if it receives a license from the FDA. He said it is important to consider the balance of risk versus reward, and he noted that the likelihood of developing a chronic condition from a vaccine is less than one in one million.

“If you are, let's say, a nurse working with COVID-19 patients, you have a choice,” Plotkin said. “You can take the risk, which, in my view will be small, that the vaccine will give you a reaction. Or you can take the risk of getting infected. And you will have to judge which of those risks to accept.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate