It’s a Saturday night at the beginning of February, and only 30 minutes remain until tip-off for a Penn men’s basketball game against Ivy League rival Dartmouth. Coming off big wins against Harvard and Temple, one would think the student body would be lining up to get inside the Cathedral of College Basketball.

But with the action just minutes away, the student section is so empty that there is still time to snag a coveted courtside seat. While there are currently more student-athletes warming up on the basketball court than there are students in the stands, the general attendance sections are beginning to fill up.

Many alumni have come back to visit their alma mater, some with children, to take in the game. Countless gray-haired supporters, hoping for a return to their glory days, also dot the home section. Two men wearing “Class of ‘72" sweatshirts and sporting wrinkles each buy a box of popcorn and take their seats near half court.

But something is different about the Palestra than when these two were students.

As more time passes, the opening tip is moments away. The student section is now around 40% full, but that number doesn’t tell the whole story.

The area designated for current undergraduates is not completely composed of average students. Many other Penn athletes have come in groups to support the team. There are even some who have snuck in that look much too old to be students.

The Quakers dominate the Big Green as play begins, coasting into halftime with a 28-14 lead. With plenty of big plays so far, the crowd is constantly applauding. But the student section lacks a certain energy.

Even though it has been an exciting game to watch, the Penn students who have shown up have remained in their seats the entire time. Every highlight-reel dunk or steal is met with soft applause — not the overwhelmingly loud cheers that are associated with basketball student sections across the country.

On a night when the Quakers would go on to fight off a Dartmouth comeback and further establish themselves as an Ivy League Tournament contender, the student section's biggest reaction of the night very well may have been when a fellow student finally won the infamous layup, free-throw, and three-point contest played during a timeout.

This is a familiar scene as of late at the Palestra. Two weeks earlier, Big 5 rival Saint Joseph’s made the trip across town, and so did its fans. While Penn’s student section was slightly fuller for that game than it was against Dartmouth, St. Joe’s fans often roared louder than the students wearing red and blue.

Game-day scenes like these signal that the culture surrounding basketball at Penn is not the same as it was during the Quakers’ basketball heyday.

***

Why does the Palestra, commonly referred to as the Cathedral of College Basketball, routinely struggle to fill its 8,722-seat capacity?

After all, the history of college basketball cannot be written without Penn. In addition to competing against historic Ancient Eight rivals on a weekly basis, the Quakers also compete in Philadelphia’s Big 5, a yearly round-robin that determines the city’s best team. The Palestra is recognized as an integral part of college basketball’s history and inception.

Penn prides itself on having a diverse student body with differing interests, but discussions with many students showed that their reasons for not attending games were mostly the same.

As an Ivy League school, Penn carries an identity as an academically rigorous institution, where students are often consumed by their studies and extracurricular commitments. Undergraduates often find themselves moving from class to class during the day only to attend several club meetings later that night.

Perhaps the simplest explanation behind declining student attendance at Penn games is that students just don’t have the time. The Daily Pennsylvanian talked to students in order to find out exactly why attendance is not what it once was.

“A lot of times, I have a lot of work and may only have an hour,” Wharton senior Trista Vatavuk said. “Depending on the weekend, you do have a lot of work, so it’s not even like you get to choose other social things over basketball games.”

This explanation proved to be consistent across schools, years, and backgrounds.

“[It’s] mostly just me being busy. I do so much, so I don’t really go to anything that I don’t need to or that isn’t at the top of my priorities,” said Derek Nhieu, the president of the Class Board of 2023.

While it is easy to say that Penn students are just busy and always have been, the numbers tell a different story.

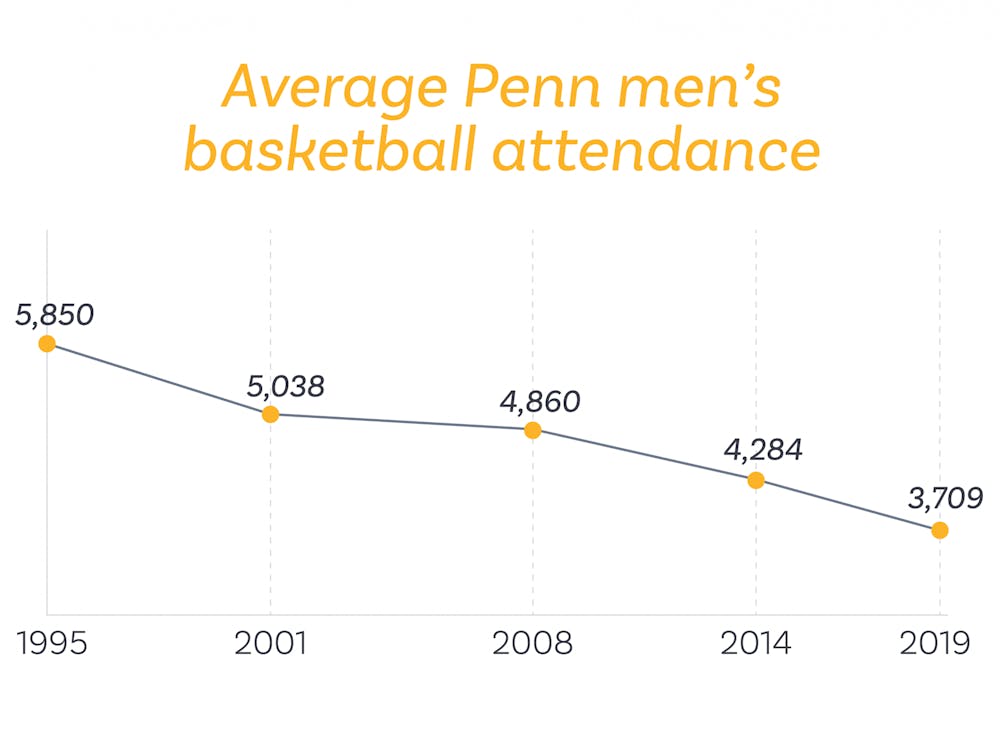

The decline in attendance at Penn men’s basketball games is the result of a trend that has slowly evolved over the past two decades. According to the NCAA’s official data on college basketball attendance, the average attendance at a Penn home game from the late 1970s to the end of the 1990s was frequently around 5,000 people. In many cases, that number was closer to 5,500, and in some years it even exceeded that total.

For that portion of Penn’s illustrious basketball history, Big 5 basketball was king in Philadelphia, and competition for the crown was strong every year. The Quakers were also consistently a top-two Ivy League team that turned NCAA tournament berths into the program’s new normal.

Entering the 21st century, Penn men’s basketball continued to be a consistent, high-caliber program that competed at the national level. Attendance at the team’s games also seemed to have carried over its 20th century totals, as the average attendance in 2000 was a respectable 5,571 people.

This trend did not last long, however, as the early 2000s brought along the start of the decline in attendance at the Palestra. Only five years after the Quakers played in front of an average of 5,571 people, the average attendance at Penn home basketball games fell to 4,620 in 2005, a year in which the team made the NCAA Tournament.

This new trend continued throughout the rest of the 2000s and into the 2010s. In 2009, for the first time in decades, the average attendance at Penn home games was under 4,000 — 3,656, to be exact. At the same time, Penn began to lag on the court, as the team struggled to compete in the Big 5 and reach March Madness. A trip to face Kansas in 2018 ended an 11-year NCAA Tournament drought.

“I hope we get back to the NCAA Tournament, because I have friends who go to Duke, and they have much more fun [at games] than I would,” College sophomore Michael Hua said.

While student attendance has been on a steady decline for decades, alumni support of the program has remained strong even as the Quakers struggle to return to the level they were at in the 1980s. Through their strong attendance, Penn alumni have clearly demonstrated that they are more passionate about Penn Athletics than current students.

When most students arrive on campus, their knowledge about Penn basketball, as well as their interest in the sport, is limited.

“I understood we had a rivalry with Princeton, and I understood the Palestra, and I knew about the Big 5,” College sophomore Jaden Cloobeck said. “But that was something I picked up at Penn. When I was first applying to Penn, I did not [know] anything about the basketball team specifically.”

In some cases, the disconnect between students and Penn Athletics is even greater.

“Thank you for enlightening me on the fact that we even have a basketball team,” Wharton freshman Sukanya Kennamthiang said when asked if she had been to a Penn basketball game.

For certain selective schools, college basketball is king. Villanova and Duke are nationally known as both academic and athletic powerhouses with competitive admissions. In fact, Villanova routinely experiences a surge in applications following its NCAA Tournament successes. At these schools, student social life revolves around when and where games are being played.

At universities like Villanova, it is commonplace for students to enter competitive raffles just to secure a seat. On the other hand, at Penn, students are incentivized by rewards and promotions just to get them in the door.

Before Penn’s recent game against Big 5 rival Temple, students in attendance were eligible for the chance to make a $10,000 half-court shot. This promotion is just one of many, as Penn Athletics also uses the Penn Rewards app that offers students a chance to earn points for attending sporting events. These points then make students eligible for a variety of prizes.

Not only are students at schools like Villanova committed during games, but they are also committed to pre and post-game activities. Taking these activities into account, students at these schools are often blocking out nearly five hours for a single game. Although Penn and its associated activities consume much of its students’ time, there is little reason to believe that students at Villanova or Duke are significantly less busy.

These similarities suggest that if Duke and Villanova students can give up an entire night for a basketball game, Penn students should have the time to at least walk in the doors.

Thus, there must be a deeper explanation for Penn’s declining attendance — culture.

While many students cite time constraints as their reason for not attending games, this may not be entirely accurate. Penn is widely known as the “Social Ivy,” a reputation that it has earned in large part as a result of the strong Greek life presence on campus, as well as many other social clubs and events.

While most Penn students do have time for social events, they would rather attend a BYO, go to a frat party, or even stay in than go to a Penn basketball game. With the average college basketball game running two hours long, many students simply prefer their social events to be a bit shorter.

“That’s the thing about basketball games. They are pretty long, so I feel like it’s hard to commit to those few hours when I can just go to dinner with a friend for 45 minutes,” Vatavuk said.

While most students have trouble making time for games, some have found unconventional reasons to go.

“I’ve found the rewards app really cool; I decided I want to get all the awards. I saw after 5,000 points you get a watch, so I’ve been going to a bunch of different sporting events," Wharton freshman Carson Sheumaker said.

Even though there is a contingent of students who faithfully attend games, many reported that they have a tough time getting others to join them.

"I have frequently tried to bring friends to games. Sometimes it works; many times it doesn’t work," Sheumaker said.

As opposed to other schools where many students’ social lives revolve around the basketball schedule, at Penn, basketball games are generally not seen as viable social events.

“When I was in high school, going to games was a tradition, but I feel like at Penn going to games is not a tradition,” Cloobeck said. “This is more about how we work hard, and we play hard, and we choose how we want to play.”

Some students noted that the Palestra is too far of a walk for them to consistently attend games. While the arena can be nearly a mile away for students who live off campus, this is hard to believe as well, as many students are known to frequently travel much farther to Center City for various social gatherings.

“Friday is a day to catch up with people I don’t get to see as much during the week, and I think ideally we wouldn’t go to a basketball game,” Wharton sophomore Merrick Eng said. “We would probably go somewhere else that is more chill.”

If there is one overarching theme, it is that the decline in attendance at Penn basketball games comes from a culture issue that stems from student perception of what is important.

There is no doubt that Penn students spend their weeks hitting the books and let loose on the weekend — the school follows a “work hard, play hard” social schedule.

But taking in a basketball game at the Palestra? For most, that's just not the way they want to play.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate

Most Read

More Like This