Datamatch lets students choose whether they are looking for "love," "friendship," or "anything, really."

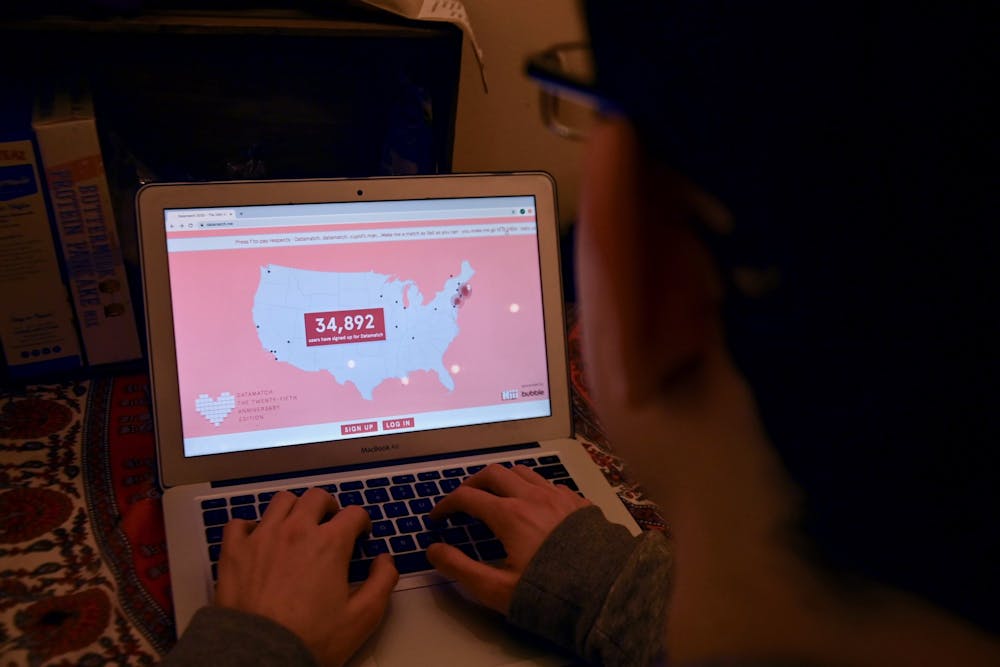

Credit: Maria MuradCollege matchmaking service Datamatch launched at Penn for the first time Feb. 7. So far over 1,000 romantic hopefuls on campus have registered to be paired up in time for Valentine's Day.

Created by the Harvard Computer Society in 1994, Datamatch is a free website that uses an algorithm based on answers to lighthearted university-specific questions to provide its surveyed participants with around 10 matches from their university on morning of Valentine's Day. There are 26 schools participating in this program this year, including Brown University, Princeton University, and Yale University, according to The Harvard Crimson.

As of Thursday night, 1090 Penn students, both undergraduate and graduate, have signed up for Datamatch. The service's website also shows a statistical breakdown of participants' dorm locations, with the largest number of students living off-campus and in the Quad, at 381 and 173, respectively. Of the participants, 352 are sophomores, 327 are first years, 201 are juniors, 156 are seniors, and 51 are graduate students.

Wharton and Engineering sophomore Shaya Zarkesh said he wanted to introduce Datamatch to Penn after hearing about it from his friend at Harvard who works on the program's design and web development.

"I thought this was a good rendition of student matchmaking service," he said. "With funny questions that are not-so-serious, [it is] a more fun version of dating sites."

Zarkesh worked with several friends from Penn to craft relatable survey questions, which are specific to each school. For Penn's version, questions include, "Ben Franklin shows up at your doorstep at 3 a.m. What do you do?" and "Which dining hall are you?"

College sophomore Harrison Chen said he signed up for Datamatch as a fun experiment after a Facebook post about the service piqued his interest.

"I read the basic history and overview of the website and thought it was cool to try out and see what kind of questions they would ask," he said.

Wharton first-year Derek Nhieu said he found out about Datamatch through a similar way – the popular Penn Crushes page on Facebook. Nhieu said he hopes to find romance as well as new friends through the service.

Unlike many dating apps, Datamatch also offers its participants a platonic option. During the sign up process, students can choose whether they are looking for "love," "friendship," or "anything, really."

Zarkesh emphasizes that the casual, fun nature of the website.

"I don’t even know if we can call it a dating app or dating service," he said. "It’s a funny thing to use as an excuse to meet new people."

Nhieu also praises the accessibility of the survey, as the website link was easy to distribute and the survey was only twenty questions.

"College students are too busy," he said. "People don’t necessarily have time to sit down and meet new people, so Datamatch seems to have quick results and be very effective in the short-run."

To match up students, the Datamatch team uses a "super secret" algorithm based on the survey question answers, Zarkesh said, who does not know the details of the algorithm himself.

Chen believes Datamatch's secret algorithm sets it apart from other dating services, like Tinder, which he said employ superficial mechanisms to pair users.

"[Datamatch is] interesting because it's based on algorithms, and it’s a matching process and survey answers instead of superficial dating apps where you swipe left and right just based on the way you look and a short bio," Chen said.

However, data experts are wary of the algorithm's ability to provide optimal matches.

Vice-Dean of Analytics at Wharton Eric Bradlow said it is hard for algorithms to measure certain traits, like humor, in matchmaking.

"Some things are easier to measure that are more objective in nature, while some things are multidimensional in nature," he said. "You could be someone who enjoys humor, I could be someone who also enjoys humor, but we could enjoy different types of humor," he added.

Wharton senior Vivian Li, who is the former president of the Wharton Undergraduate Data Analytics Club, said that when something is recorded in data, although a lot of information can be gained, a lot can also become lost. Like Bradlow, Li said that algorithms cannot always differentiate nuanced information.

"Some types of information – personality, sense of humor – are hard for an algorithm to handle," she said.

Still, Chen enjoys the humorous and social outlet Datamatch offers during Valentine's Day.

"They [Datamatch team] preface it as something not super serious," said Chen. "At this point, I’m just really curious to see what would happen on Friday when they release the results."

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate