Criminology professor at the University of South Florida, Ojmarrh Mitchell, talked about pretextual traffic stops, where police officers make individuals pull over and proceed to investigate them for an unrelated offense.

Credit: Sharon LeeOjmarrh Mitchell, a criminology professor at the University of South Florida, spoke about racial profiling and proposed ways to combat the issue at Penn on Wednesday.

During Mitchell's talk, which was part of the Criminology Department's Fall 2019 Colloquium Series, he argued that while racial profiling is often attributed to implicit bias, structural and institutional factors play a bigger role.

Mitchell talked about pretextual traffic stops, where police officers make individuals pull over and proceed to investigate them for an unrelated offense. He shared the story of Robert Wilkins, a defense attorney who was pulled aside by the Maryland State Police for a drug search on the grounds of speeding. While Wilkins knew his rights and refused to consent to a search, he ended up standing out in the rain with his family as the police and a drug-sniffing dog searched his car, only to find him innocent.

“Robert Wilkins was stopped because he fit a racially biased drug courier profile. And hence the term, racial profiling,” Mitchell said.

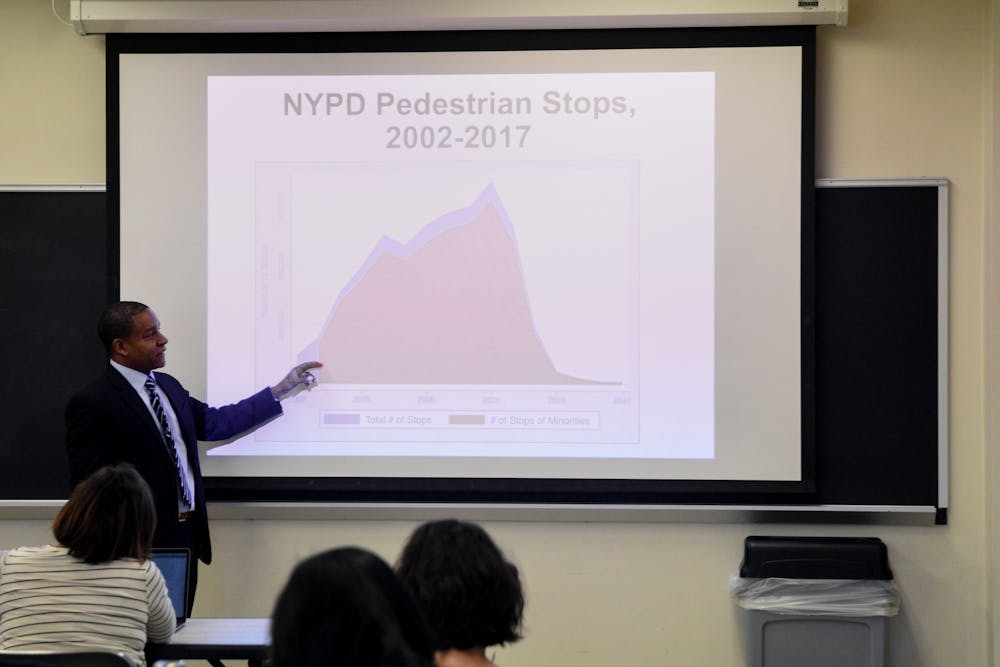

He said that although pretextual stops disproportionately affect people of color, they are conducted as standard procedure in policing nationwide because policymakers hope they will reduce crime.

“Proactive, aggressive, investigatory stops have become an essential element of U.S. policing,” Mitchell said. He cited the example of the Drug Enforcement Administration's Operation Pipeline, a three-day training course for uniformed police officers, which taught pretextual stop tactics to more than 27,000 police officers in 48 states to identify drug traffickers.

Mitchell said current research on racial profiling focuses on implicit bias, but studying larger structural issues could lead to more effective policies. He said pretextual stop tactics stem from the structure of police forces, where officers who conduct frequent investigatory stops are rewarded and those who do not are penalized.

Attendees remained curious and skeptical about Mitchell's perspective on implicit bias, calling it "one-sided" and "relative."

While some state legislatures and police departments have tried banning the mention of race from drug courier profiles to deal with this problem, Mitchell said this approach is limited because it focuses on police reports rather than the root causes of racial profiling, and the phenomenon persists despite new legislation.

Mitchell argued that implicit bias training is ineffective because it mimics classroom learning, instead proposing a policy academy model combining classroom learning, practice, and coaching. He also advocated the use of technology to monitor police actions, describing how the New Orleans Police Department posts officers' body camera footage for public viewing. To better understand the mechanisms producing bias, Mitchell added, researchers should conduct interviews with officers and communities affected by racial profiling.

Attendees remained curious and skeptical about Mitchell's perspective on implicit bias, calling it "one-sided" and "relative."

Syed Hassan Zulfiqar, a first-year Criminology master's student, said he has faced racial profiling in his home country of Pakistan. He hopes to return to Pakistan after graduation and help the Pakistani government develop policies to prevent racial profiling. Hassan said while he came to the event to gain insights for future research, Mitchell's suggestions may not be received the same way in Pakistan as they would be in America.

“Since we don’t really have good education backgrounds, [there aren't] funding opportunities for students back from Pakistan to pursue research work that could be policy that the government could actually implement, so that’s sort of a drawback," Hassan said.

Mitchell remained hopeful that change is possible.

“Every police organization has the ability to set out what they value,” he said. “We’ve all internalized these stereotypes, so it’s not good that you have these biased actions, but it’s normal.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate