From Clay Graubard

Last week, undergraduate students at Georgetown University voted overwhelmingly in favor of creating a fund to benefit descendants of 272 enslaved men, women, and children who were sold in 1838 to save the university’s finances.

Under the proposal, a mandatory fee of $27.20 per student per semester would fund a nonprofit, run jointly by Georgetown students and descendants, which would allocate money to charitable causes benefiting the descendants. Students turned out for the election at a record-high rate, according to Georgetown’s student newspaper, but the proposal needs approval from administrators before it can be implemented.

This referendum is the culmination of years of student activism at Georgetown since the university launched its Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation in 2015. The high turnout in last week’s student government elections at Georgetown reflects the extent to which the student body there has taken an active role in determining how their school will address its historical ties to slavery. It’s time for Penn’s student body to do the same.

Penn has recently joined schools such as Georgetown, Harvard University, Brown University, Yale University, Princeton University, Columbia University, and the University of Virginia in beginning to publicly reckon with historical ties to slavery.

At most of these schools, administrators convened research groups to study institutional ties to slavery following increased attention to such connections. Penn is one of a few colleges where research programs on institutional ties to slavery originated in undergraduate history courses. The idea for the Penn and Slavery Project came out of a spring 2017 course taught by History professor Kathleen Brown, and students have contributed research to the project every semester since fall 2017.

These undergraduate researchers, as well as others involved in the project, are laying the foundation for Penn to reckon with its connections to slavery. The Penn student body ought to recognize this work by taking the time to learn about the project’s early findings, just as Georgetown students have worked to understand their institution’s role in the slave trade.

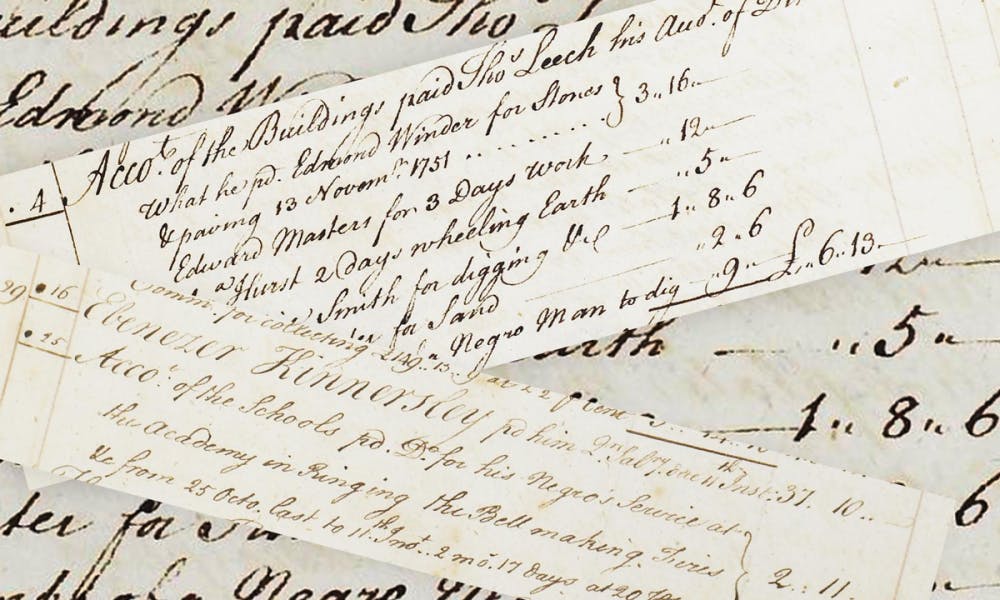

The Penn and Slavery Project’s research has revealed that a substantial number of Penn’s founding trustees owned slaves. These trustees also sent William Smith, the University’s first provost, and John Morgan, the founder of the Medical School, to South Carolina and Jamaica to raise funds for the University from wealthy slave owners. “Smith and Morgan's efforts ensured that the university would stay open because of wealth earned from slave-labor,” the project’s website states.

Additionally, the student researchers have highlighted how the Medical School’s faculty and alumni pioneered theories of race “science” used to defend slavery and to create a scientific basis for white supremacist ideologies. For example, in the mid-19th century, Medical School professor Samuel Morton catalogued the sizes and volumes of hundreds of human skulls to support his theory that mankind could be divided into five separate races and ranked by intellect. This research was used to justify chattel slavery as consistent with a natural racial hierarchy, and today Morton is often called the “father of scientific racism.” This pseudoscience of racial difference remains influential today in more subtle ways; a 2016 study at the University of Virginia found that an alarming percentage of white medical students and residents held false beliefs about biological differences between black and white people, including that black people have thicker skin than white people.

Penn’s history is not the same as Georgetown’s. There is no evidence that Penn ever owned enslaved people or that Penn directly profited from the sale of slaves in the way Georgetown did. Still, we must critically examine how Penn contributed to racial injustice during the antebellum period, especially in light of the University’s more recent history of expanding at the expense of black communities in West Philadelphia.

When the extent of Georgetown’s complicity in the slave trade became widely known in 2016, Penn’s director of media relations denied the University had any direct historical ties to slavery. But in early 2018, following the first semester of the Penn and Slavery Project research, President Amy Gutmann and Provost Wendell Pritchett released a statement announcing the formation of a new working group on slavery and praising the group’s work to cast “a new light on our historical understanding of the reach of slavery’s connections to Penn.”

“It is important that we fully understand how it affected our University in its early years and that we reflect as a university about the current meaning of this history,” the statement read.

No institution can fully repay the moral debt owed for helping to promote slavery, but supporting the Penn and Slavery Project’s efforts to investigate the University’s history is a good first step. The University should continue to support the work of the Penn and Slavery Project. The Daily Pennsylvanian Editorial Board encourages all members of the Penn community to take the time to learn about this research on the history of our institution. Further information is available on the project’s website at pennandslaveryproject.org.

Editorials represent the majority view of members of The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. Editorial Board, which meets regularly to discuss issues relevant to Penn's campus. Participants in these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on related topics.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate