The 2019 Intercollegiate Psychedelics Summit featured eight presentations from researchers in areas ranging from philosophy to psychiatry to pharmacology.

Credit: Seavmeiyin KunPenn's first annual psychedelics summit brought together more than 160 researchers, practitioners, philosophers, students, and psychedelics enthusiasts to cultivate discourse on the potential applications of the controversial drugs.

The 2019 Intercollegiate Psychedelics Summit, held on April 4 and 5, featured eight presentations from researchers in areas ranging from philosophy to psychiatry to pharmacology. It was organized by the Penn Society of Psychedelic Science, an interdisciplinary student group dedicated to building an academic community around studying psychedelics and consciousness.

The summit focused on the current “psychedelic renaissance,” a term coined for the recent resurgence of interest in the clinical, spiritual, and recreational potential of psychedelic drugs. Last month, the FDA approved the use of esketamine, an antidepressant related to the psychedelic drug ketamine. Among creative and entrepreneurial circles, “microdosing," the practice of taking small doses of LSD, has gained popularity for its benefits of increased productivity and creativity.

Chris Bache, professor of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Youngstown State University, has self-administered LSD 73 times while taking over 400 pages of careful notes to explore concepts like consciousness, death, and the existence of a conscious intelligence in the universe.

It was not always this way, Chris Bache, professor emeritus of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Youngstown State University, said. Psychedelics, a class of drugs known for their mind-expanding and ego-removing effects, were classified as “schedule 1” substances in 1970 in the Controlled Substances Act, pushing recreational use and research on their medical applications underground.

David Nutt, a professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, said prior to 1970 there was significant research into the potential for using psychedelics in psychiatry. Additionally, Nutt said, many renowned scientists — including Nobel Laureates Francis Crick, responsible for discovering the double-helix structure of DNA, and Kary Mullis, who developed the polymerase chain reaction method — claimed that LSD helped them reach their groundbreaking discoveries. However, the involvement of psychedelics in controversies such as Nazi experimentation in World War II and anti-Vietnam war counterculture led the United States government to criminalize them.

“I don’t think there’s anything unique besides the stigma and the history,” Jonathan Moreno, a Perelman School of Medicine professor of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, said in reference to psychedelics.

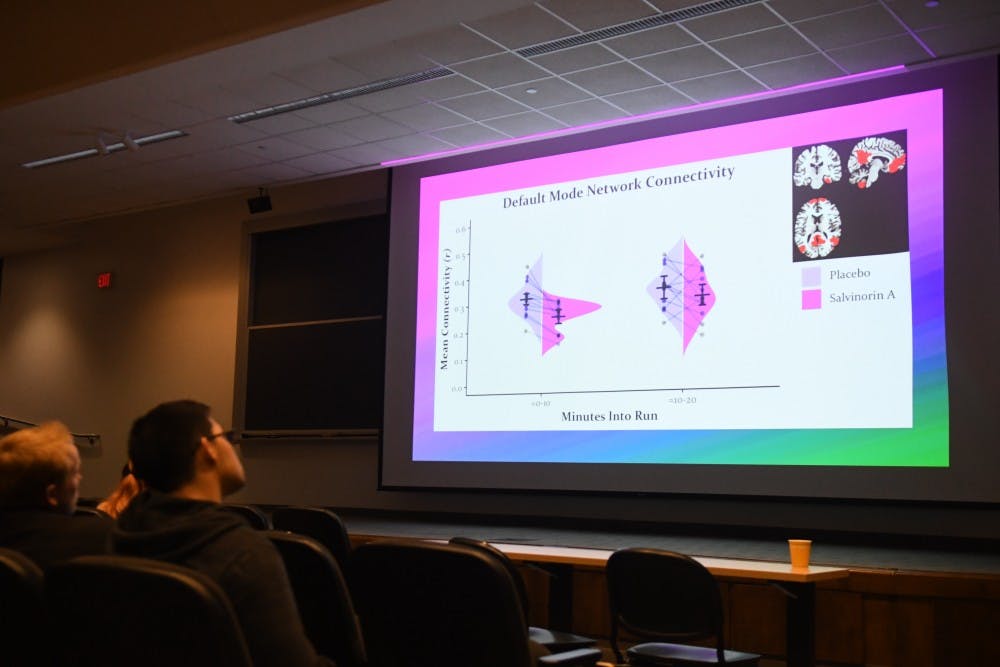

Attendees at Manoj Doss's talk in Meyerson Hall.

Other speakers emphasized the possibilities for using psychedelics in clinical settings. Psychiatrist Matthew Brown said psychedelic experiences can help patients with personality disorders develop new thought patterns. Frederick Barrett, a psychiatry professor in Johns Hopkins University’s Psychedelic Research Unit, talked about research that suggests psychedelics use can reduce anxiety and depression in cancer patients.

Bache added that psychedelics can also help individuals venture into the spiritual realm. The professor of religion and philosophy said he self-administered LSD 73 times between 1979 and 1999, taking over 400 pages of careful notes to explore concepts like consciousness, death, and the existence of a conscious intelligence in the universe.

Bache said during these experiences of elevated consciousness, he experienced multiple deaths, a Hell Realm, profound oneness and love with the universe, and the lives of numerous women. These experiences showed him that Western modes of thought surrounding religion are too narrow to describe the creative intelligence of the universe, an entity he refers to as “The Absolute.”

“I outgrew god, in a way,” Bache said.

Of psychedelic experiences, he said, “If you take precautions and do the necessary work, then ordinary people can benefit enormously.”

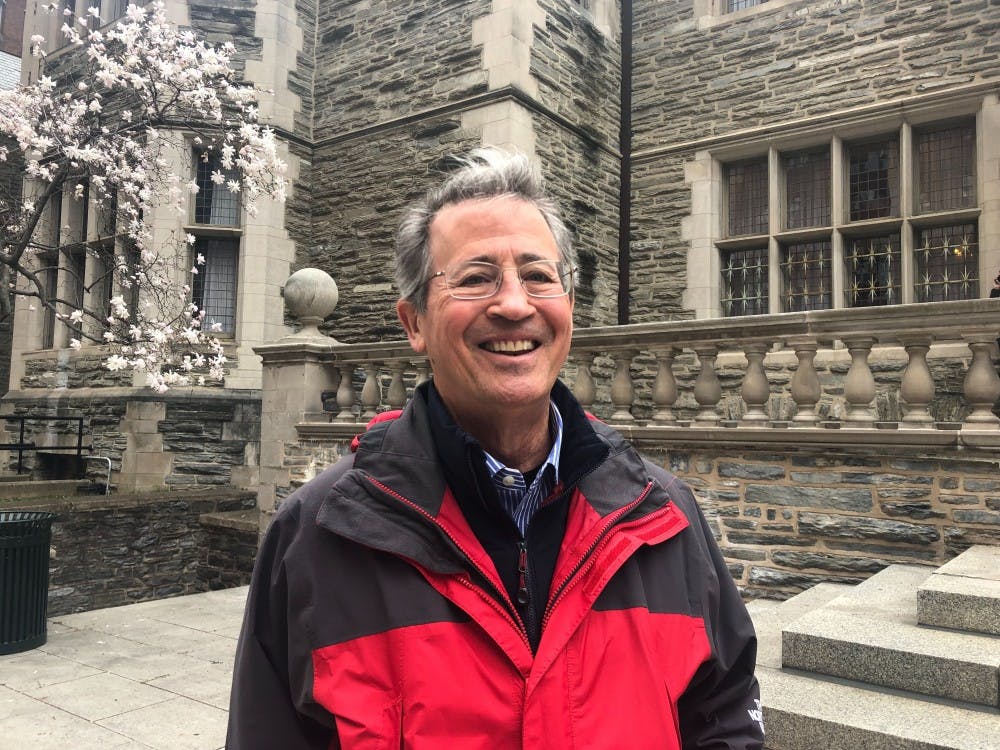

Manoj Doss, a drug and memory researcher at Johns Hopkins, spoke at the event.

Not all speakers were certain of the benefits of psychedelics. Manoj Doss, a drug and memory researcher at Johns Hopkins, expressed concern that much research on psychedelics is conducted by individuals with little background in science who are inspired by personal experiences with the drugs.

“I actually do think there’s this false hope that we’ll learn something about consciousness with these consciousness-altering drugs,” Doss said. “They’re not finding anything novel that the hippies didn’t tell us.”

The conference included a social event at City Tap House, encouraging attendees to develop relationships with others at the conference.

“The best thing was the people,” Harvard junior Kenneth Shinozuka, a co-founder of the Harvard Science and Psychedelics Club, said. “These past 26 hours were among the most special events I’ve ever experienced.”

Event organizer Victor Pablo Acero, a second year bioengineering doctoral student, said the Penn Society of Psychedelic Science plans to expand the conference into an annual event and build an intercollegiate network dedicated to studying psychedelic science.

“It’s unfortunate that [psychedelics have] been misunderstood in the past," event organizer and Engineering senior Alex Zhao said. "The clinical applications and science of psychedelics hold tremendous promise if approached with care in a responsible way.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate