Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax (Photo by Lee District Democratic Committee | CC BY 2.0)

Amid the present political firestorm in Virginia, Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax has at the time of publication been accused of two sexual assaults. Fairfax denied both accusations and hired the law firm that represented Brett Kavanaugh during his hearing this past fall. Meanwhile, his first accuser hired the lawyers who represented Christine Blasey Ford. Many conservative commentators like Tucker Carlson have seized upon the obvious parallel to attack what they see as the “hypocrisy” of liberal support of the #MeToo movement, as prominent Democrats such as Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) have opted to remain silent on the issue. While there are also many prominent Democrats — such as senators Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Cory Booker (D-N.J.), and Tim Kaine (D-Va.) — who started calling for his resignation after the second accusation, these commentators have still touched upon a fascinating idea. Whether or not we believe or act on allegations — in politics or on our campus — often depends strongly on how we feel about the accused.

Yet another example is former president Bill Clinton, who after 20 years still hasn’t faced his #MeToo reckoning in the face of several sexual assault allegations, and is instead speaking to millions of people on his “An Evening with the Clintons” tour. Meanwhile, Monica Lewinsky wrote last February about developing post-traumatic stress disorder from the entire ordeal. As she put it, “I’m beginning to entertain the notion that in such a circumstance the idea of consent might well be rendered moot.” So why is it that we let certain people avoid accountability?

We rightfully believe sexual assault to be a monstrous act and portray sexual assaulters in our culture as villains. But this means that when people we like are accused of being sexual predators — such as Bill Clinton, who left office with a 65 percent approval rating — we can’t reconcile our image of that person with the monsters we imagine. Often this means that we ignore the assault claims or say it must have been a misunderstanding. Or it can mean that we lash out at the accusers — like Gloria Steinem, who in a 1998 New York Times op-ed called accuser Kathleen Willey “old enough to be Monica Lewinsky’s mother.”

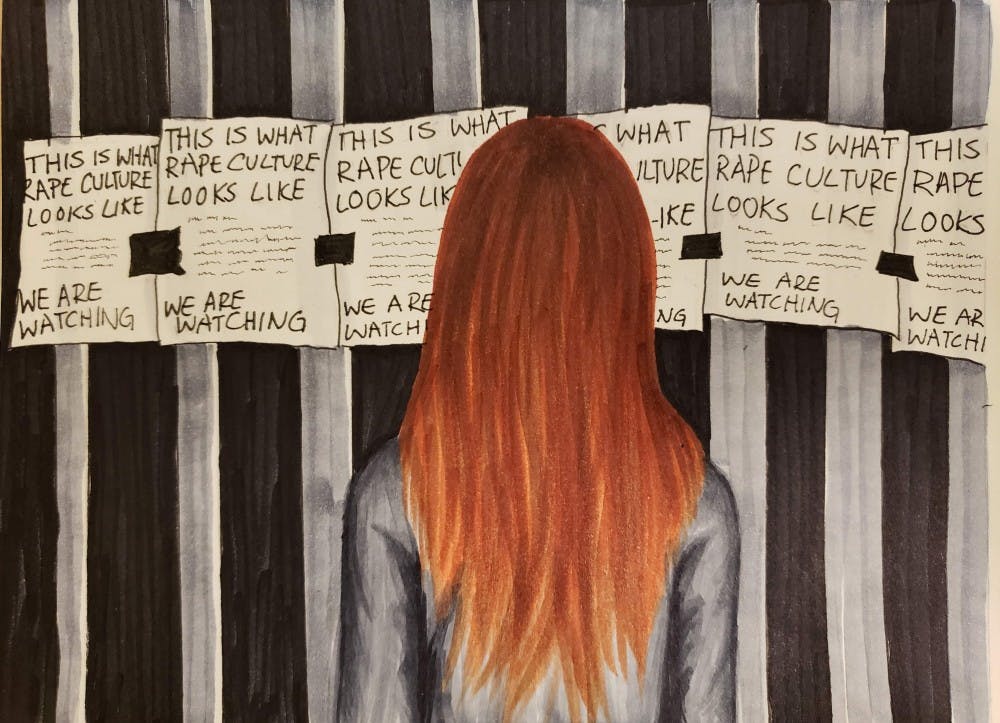

We also see this trend of not holding our friends accountable in our campus culture. When I was sexually assaulted by a formerly close friend freshman year, many of our mutual friends could not reconcile my accusation with their image of my assaulter. As a result, several of them chose to dismiss the claim entirely, even after it was confirmed by a school investigation. These friends were people that prided themselves with being concerned about social justice and minority rights, and yet even they ended up perpetuating this really pervasive element of rape culture. Other friends have also told me how their assailants also go on without social sanction, even marching in Take Back the Night rallies and sharing MARS events on Facebook.

To change this culture, we need to be more empathetic towards those who come forward with allegations, even when this means calling into question those we love. We shouldn’t rush to discredit or silence people just because they are accusing our friends. Given that the reporting process is pretty traumatic itself, involving cross-examinations and having each retelling of your story picked apart for inconsistency, we should really offer these people support. Support is asking them what you can do to help them and actively listening to their needs. Support is not using accusers as political hammers to beat your opponents, like the commentators mentioned previously did.

In the case of pending investigations or accusations, support does not have to mean abolishing the presumption of innocence. Although it is a delicate situation, it is possible to be actively supportive of accusers while not blindly rushing to support one side in the absence of a completed investigation.

But in the case of confirmed accusations, we also have to start holding the accused accountable for what they did. We can’t make excuses for their behavior and we can’t pretend it didn’t happen. It is by engaging with those two non-responses that we passively allow rape culture to continue on this campus.

Perhaps the climate is changing on a national level. The calls for Fairfax’s resignation from even other Democrats show that the party’s tolerance for sexual predation is lower than it once was. Although Bill Clinton hasn’t met with any public condemnation, his name has been quietly dropped from the formerly named Kennedy-Clinton Gala, and many Democrats no longer wish to campaign with him anymore. But we need to make sure that our condemnation of sexual predators is something we apply to the people in our lives, not merely the politicians we vote for.

We’re all willing to say we oppose rapists, but what would you do if the rapist was your friend?

REGINALD LAMAUTE is a College junior from Chapel Hill, N.C. studying Chemistry. Their email address is rlamaute@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate