A year ago, in my very first column for The Daily Pennsylvanian , I wrote about Aziz Ansari and my views on the nascent #MeToo movement.

In the past year, I’ve followed the movement, first with hope, then trepidation, and finally slight waves of despair, as the movement faded from a dominant cultural phenomenon to second-rate news. In some ways, this was inevitable. Nothing, no matter how outrageous, stays shocking forever.

But mostly, it feels like the promise of the movement has dissolved into empty gestures and performative rhetoric, while the predatory men the movement outed crawl back into public life.

The Ansari story was a particular flashpoint during the waves of allegations about sexual harassment and assault that seemed to come in a never-ending flood last winter. Unlike the allegations against others named in the movement, like Harvey Weinstein, Charlie Rose, Louis CK, and Matt Lauer, the allegations against Ansari were not part of a documented pattern of workplace misconduct and harassment. Instead, it was a stand alone account about a date between two single adults that went wrong.

The Ansari piece was, and remains, a flashpoint for those who have valid critiques about how the reporting of the story was handled, and those who have concerns that it was evidence of a cultural movement running off the rails.

When I wrote about the story last year, I did so because I thought that it touched a nerve, especially for me as a woman on a college campus where hook-up culture dominates. Before, the stories revealed in #MeToo seemed important, but far removed from anything I had actually experienced. The Ansari story felt familiar and accessible, and reflected in it was the beginning of a conversation that seemed like it would go beyond the workplace and start addressing other insidious double standards that often go unremarked and unspoken when it comes to sex, consent, and gender. I wrote, “It became clear to me that there is no consensus of what the term sexual assault means, and its usage becomes an easy way to stop or deliberately confuse conversation about how we as a society approach sex, and how our attitudes about sexual relations are broken.”

I was hopeful in the aftermath of the rage and pain that #MeToo had exposed, that we would move past the stasis of public conversation and deliberation. That the tired routine of doubting women and minimizing the impact that sexual assault and harassment have on their lives would be over and we could move to the more nuanced conversations I feel we so desperately need to have.

I was hopeful that what would happen next would be lasting change. I hoped that once we worked from a basic understanding of the fact that harassment and assault are, in fact, bad things, that they’re crimes that have victims and require consequences, we could work out how to move forward to justice and closure. I was hopeful that the path forward would stop centering the men who had committed transgressions — who are so often richer, more famous, and overall more powerful than the women they target, and put more focus on bringing justice to victims. Once consequences were actually put in place, we could talk about the possibility of rehabilitation and forgiveness.

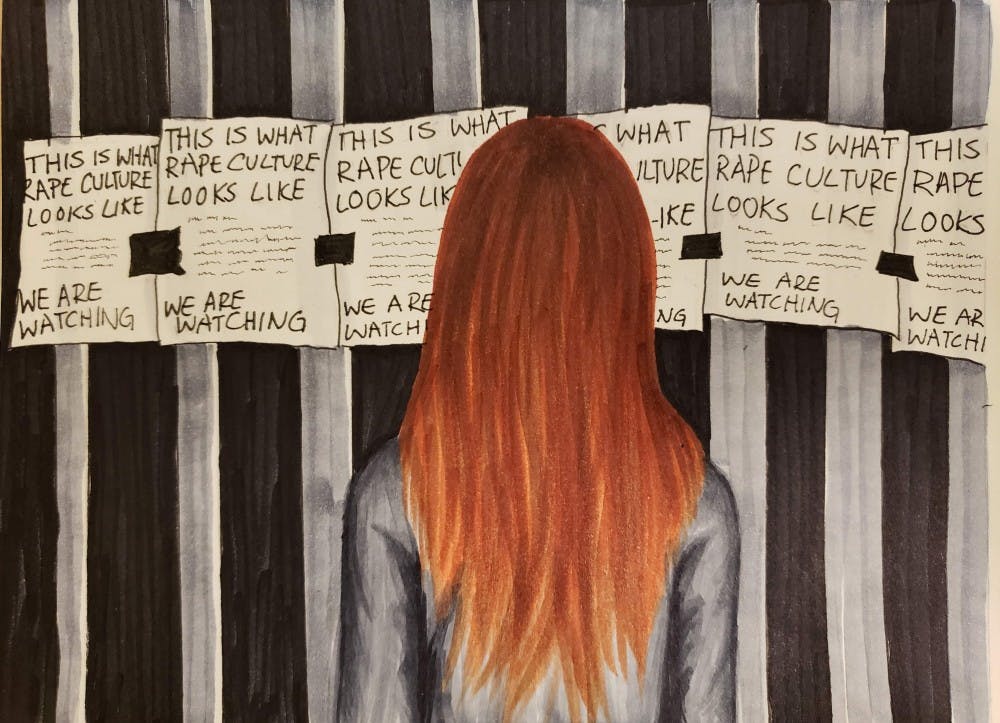

I don’t believe in a society that punishes all transgressors equally with a permanent proverbial scarlet A, or treats all transgressions as if they are the same. So often, discussion of rape culture fails to provide adequate solutions for how to rehabilitate men who commit crimes, but that’s because we’re still fighting for the genuine recognition that what these men did was, in fact, a violation.

Instead of moving us forward, the fall brought the Kavanaugh hearings — an event that seemed to confirm Marx’s affirmation that history happens twice, once as tragedy and once as farce. It was like being stuck in a horrible version of Groundhog Day, where the gains of #MeToo and the Anita Hill hearings amounted to nothing.

In addition, the sold-out comeback tour of Ansari — in which none of his material address the accusations against him — the planned return to television of Matt Lauer and Charlie Rose, and the semi-stealthy return to comedy of Louis CK seem like slow reversals of the gains that the movement has made.

A year removed from what seemed like one of the most significant steps forward in the crusade for women’s rights in my lifetime, it feels like we have failed to find solid ground on which to build any sort of long, lasting change. Lacking an understanding of the basics, conversations about the grey areas of consent and the nuances and gender imbalance have been unable to materialize.

As students, we occupy the epicenter of rape culture and sexual violence. We also find ourselves at a strange point in our lives where we actually have the time to think and act boldly about the sort of world we want to work towards after Penn.

Soon we will graduate and become denizens of workplace with prevailing cultures and unspoken norms. The habits we form here at Penn — the things we chose to expect of our friends, the organizations we decided to be a part of, the behavior we tolerate on our campus — will shape the moral compasses that guide us through our infinitely more complicated post-graduate lives. We owe it, both to ourselves and to each other, to tolerate nothing more than the best.

REBECCA ALIFIMOFF is a College junior from Fort Wayne, Ind. studying History. Her email address is ralif@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate