A dozen or so admissions officers are seated around a seminar room, each with an applicant’s documents held in front of them. One states, “accept,” and a number of hands shoot up. “Waitlist,” and up goes another number of hands. Repeat the process one last time for “deny,” beat the gavel, and a student’s future is decided. This is how I imagine the inside of a college admissions decision room.

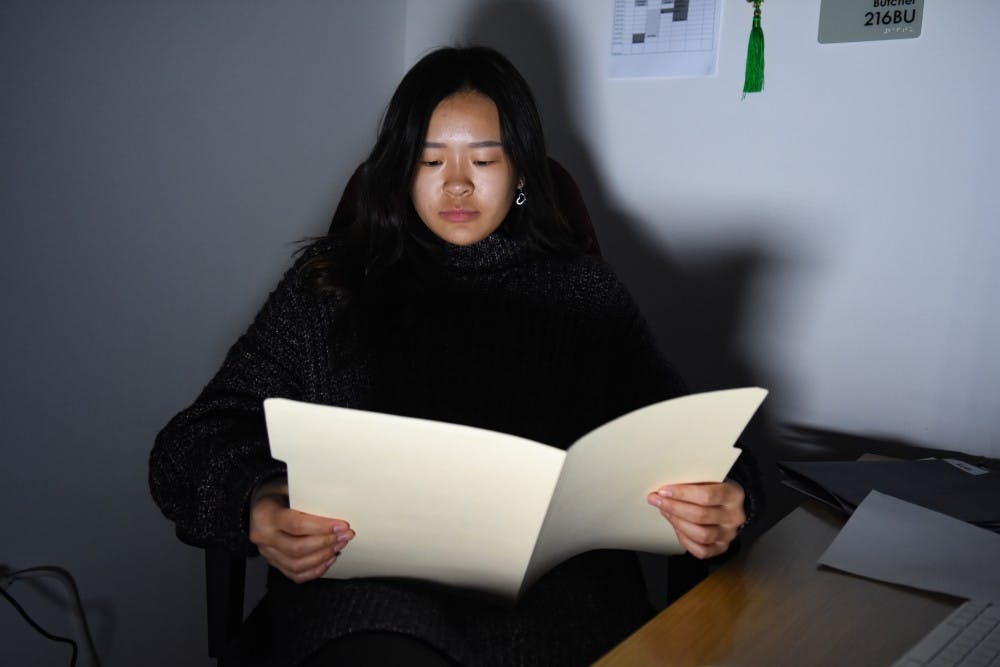

The admissions process has always been murky to me. But when I heard about the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, which allows students to view their admissions files upon written request, I was intrigued.

On Nov. 7, 2018, I sent an email to the admissions representative of my region, found through the Office of Admissions contact page. The next day, I received an enthusiastic reply from my admissions officer, who was delighted to share my request with her colleagues. 42 days later, my file was sent electronically.

My file was 18 pages long, and scrolling through it, I realized, most of it was a replica of my Common App, organized in a way that gave me no new information. Only the first page and one other page had new information. On the first page was my GPA, my senior year coursework, my SAT scores, my SAT II scores, and my AP scores. Another page wrote out the form user’s title, the date the form was submitted, and that the file was placed into the admit bin.

Most interestingly, there were four numbers, labeled "E," "I," "M," and "AI." With these letters came no description. However, AI, a number much larger than the other three could be interpreted as academic index, a score out of 240 that takes into account one’s GPA, class rank, and standardized testing scores. Two more boxes contained the words “very demanding” and “FG," presumably short for first-generation, and that was the extent of my admissions file.

Admissions files at Penn were not always this obscure. In 2015, Stanford University publicized a method of retrieving admissions files, which led to an increase in requests in colleges throughout the nation, including Penn. To combat the issue, Dean Furda planned to remove certain personal comments from applicants’ files before granting students access. The plan was put into action and today's admissions files that are available lack substantial information.

What Dean Furda doesn’t realize is that these comments in our files grant us true insight into what admissions officers think of us, not only as students but as human beings. More concrete, detailed feedback can help students better understand how to lead successful lives at Penn. Detailed comments illustrate students in a way numbers can not. They are the essence of our admissions file. Without them, admissions officers prolong the notion that students are summed up into a set of statistics — and in this case, four numbers.

Though my experience was anticlimactic, I do not regret requesting my file, and others shouldn’t either.

Many may dissuade people from looking at admissions files, saying the act is harmful. In 2017, 1986 Wharton graduate and co-founder of and director of One-Stop College Counseling Laurie Kopp Weingarten urged students not to look at their admissions files.

But, there should be no harm. Even if Penn provided more information within the admissions files, which they should, there should be no reason to feel offended — we are already students at the University. I’ve earned my spot at Penn, and four mysterious numbers and some phrases do not change that. What's more, having access to more detailed comments might help us to grow in an academic setting and professional environment.

Although the admissions file does not give the full scope of the admissions process, having the right to access it is a start. What we need to fight for is transparency. While Penn doesn’t even have a rubric for interpreting admissions files, other schools have clear guidelines along with original comments attached to their files.

Duke University has a clear-cut guideline for viewing admissions files, with six components — high school curriculum, academics, recommendations, essays, extracurriculars, and test scores — graded from one to five. Moreover, admissions readers provide a paragraph summary on the entire application.

Harvard University provides students with a summary sheet, comments from two admissions officers assigned to review their file, and their application. If students did not waive FERPA rights when applying to college, they can also see letters of recommendation from their teachers. Now, with the Harvard affirmative action lawsuit, previously highly confidential documents have been made public, including one that documents the criteria Harvard uses to judge an applicant. The document shows a grading scale from one to six, and evaluates based on academics, extracurriculars, community employment, family commitments, athletics, personal qualities, and recommendations letters.

After years of relentless effort spent preparing for admissions to top schools, students deserve transparency. We ought to have the right to receive actual feedback that can be used to advise younger friends and relatives. At a time when the admissions process is under intense scrutiny at academic institutions, it is imperative that we do our part in holding Penn accountable too.

CHRISTY QIU is a College freshman from Arcadia, Calif. studying architecture. Her email address is christyq@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate