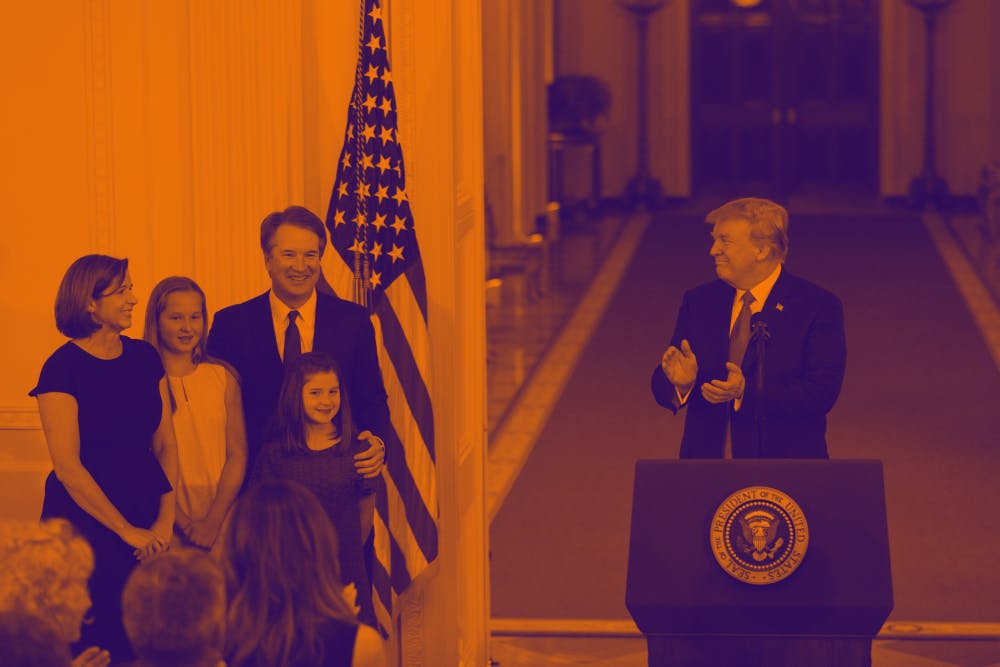

Photo Illustration by Harry Trustman

When the news of the allegations against Brett Kavanaugh first broke, I took a deep breath, flicked on my electric kettle to make myself a cup of tea, skimmed the article, and resolved to stop thinking about it.

Now, I’m abroad and everyone in my 9:30 a.m. French class is scowling, sipping their paper cups of instant coffee (the French have yet to discover the joys of regular old filter coffee), and swapping complaints about the Ford-Kavanaugh hearing.

Cecile, our teacher, who has a pixie cut and an inimitable air of Parisian blaséness, frowns and says, “Can’t you just have a coup?”

This is, of course, a joke. But it’s not entirely unserious. In the last 230 years, since the storming of the Bastille, the French have weathered five republics, two empires, and a Bourbon restoration. They tend not to get emotionally attached to their current form of government, at least not in the way we do, with all this teeth gnashing, Constitution-thumping, and invoking the names of the Founders from on high.

In so many intimate ways, I believe in the myth of America. And that myth enshrines our values in the government laid out in the Constitution. How do we tell the story of ourselves without telling a story of presidents and Supreme Court cases and solemn Oval Office addresses to the public?

France isn’t attached to its government. Long, turbulent political history has given the French proof enough that their national identity rests far outside of the current configuration of the Republic.

But in America, our politics are personal. Our political views are tied to how our visions of America and American patriotism lets nothing go down easy.

When men like Brett Kavanaugh or Donald Trump are admitted into the inner sanctum of the government, when they occupy the exalted positions that we tell ourselves belong to the very best and most moral among us, it strikes at the very heart of our national identity as Americans.

When the Senate Republicans make excuses for Kavanaugh’s behavior, when they tell us that sexual assault accusations do not exclude a man from being a justice on the highest court in our nation because it happened so long ago, when they resign from doing their elected duty by hiring an outside prosecutor and refusing to responsibly and respectfully question the witnesses themselves, what they are really saying is that this whole process has no place in the narrative about American morality.

Women, with their bodies and their traumas and their alleged personhood, have long stood outside of American political life. Why should they not continue to stand there and let the men, as they have done for so long in the history of this country, decide what is important and what is not? What men do to women, Senate Republicans would have us believe, is not important. Weighed on their crooked scales of justice, one alleged attempted rape balances quite nicely with two Yale degrees.

Since the election of Trump nearly two years ago, so much of American politics, once my favorite pastime, has filled me with rage.

For a while, I raged out loud. Maybe I liked being so angry. Maybe my rage was performative — a callback to times when women actually had things to worry about, like corsets or not being able to open their own lines of credit. Here in the 21st century, I told myself, the patriarchy isn’t actively oppressing so much as benignly rotting. Sure, the guy in the White House gropes women with impunity, but he hasn’t grabbed your pussy, so like, stop taking it so personally?

So I smothered my rage. I was the poster child of understanding. I was so tired of being a nasty woman.

But what I realized as the Weinstein allegations first broke, as the Kavanaugh news became something that I could not ignore if I tried, is that my rage has little to do with me.

So many of my friends, my acquaintances, so many of the woman I look up to, respect, and hope to be like some day — even the girls I only know from Instagram and passing glimpses in the halls — have stories just like Dr. Blasey Ford.

And they carry these stories with them. They carry the weight of their trauma, of the stories pressed to the back of their minds. Sometimes they tell their stories publicly, and in carefully worded articles and Facebook posts, and sometimes it’s the type of thing you learn in private, half-whispers in the dark.

The politics of the current moment are personal. More than that, they’re intimate, invasively so.

To pretend to be blasé, dispassionate, and a little more French about this whole thing would give quarter to the long standing idea that women’s feelings about their bodies, the truths about their own violations, and their assertions of their political rights are in fact, not valid expressions of civil participation. It would affirm that women’s pain is something embarrassing, hysterical, and best kept private, while men’s pain carries with it pomp and gravitas.

We are the stories we tell about ourselves. If Brett Kavanaugh is confirmed to the Supreme Court, the story of America will be that it, once again, does not care about women.

The story will be that the country that I was born in, the country that I love, does not care about the pain of my friends, nor the pain of the women that I admire.

So I won’t set down my rage. Not if I care about women, not if I believe them.

This burden is heavy, but no one should have to carry it alone.

REBECCA ALIFIMOFF is a College sophomore from Fort Wayne, Ind. studying history. Her email address is ralif@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate