Over the past few weeks, I have read countless headlines and declarations expressing grief and outrage at the death of Mollie Tibbets, who was studying psychology at the University of Iowa. It is understood that Cristhian Bahena Rivera followed Tibbets and killed her after she rebuffed his advances and threatened to call the police. Many accounts focused on the fact that Rivera was an undocumented immigrant, and used this tragedy as a platform for their political parade preaching the end to all undocumented residencies in the United States.

Not only does this tunnel-vision perspective of an awful situation completely bulldoze over the horror of a 20-year-old being murdered, but it ignores the very real and current threat women who do not reciprocate emotions or attention face every day in the real world.

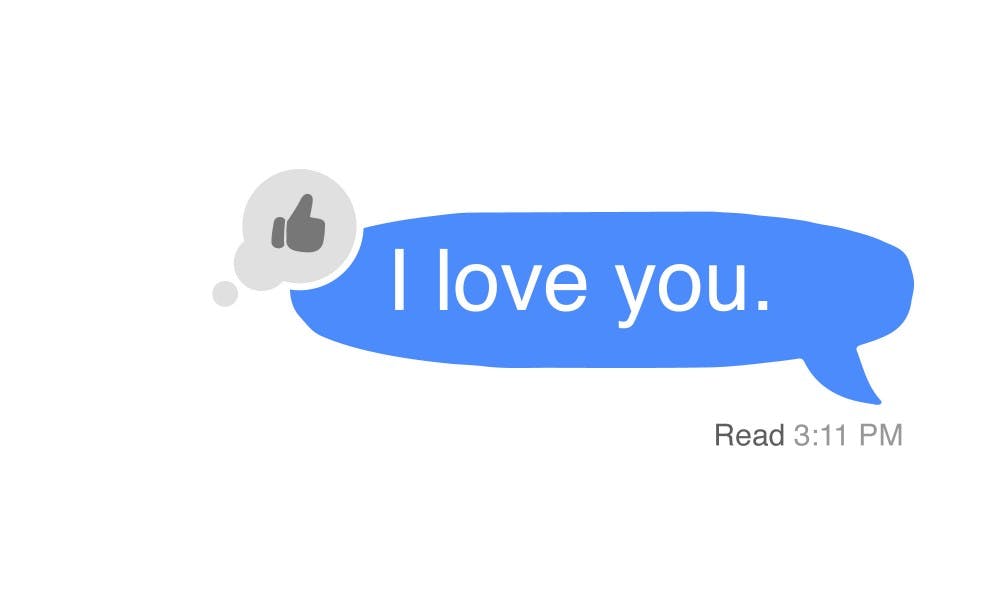

Murder is an extreme example of the consequences women are forced to shoulder when they do not requite feelings that a man has for them. Every day, friendships are folded into darts that people throw in their crushes’ faces when their feelings balloon into more. The expectation that women should be grateful for a greater development of feelings isn’t a new concept, but the consequences raining down on us hasn’t slowed. In fact, the internet has facilitated this expectation of more, and groups such as incel communities (incel standing for “involuntary celibate”) only further perpetuate entitlement, feeding off media coverage like flies scavenging the remains of a picnic.

Even the very concept of a “friend zone” is born out of bitterness. The term, whether applied to a man, woman, or non-binary person, is steeped in presumption and assumed license. The fact that we need a word to explain the phenomenon of placing someone inside an imaginary concept enforces the idea of expected reciprocity. Human connection shouldn’t be solely valued by the possibility of more.

It is understandable to have feelings for a person who doesn’t have those feelings back for you. We’re all human after all and attraction is involuntary. However, women — or anyone for that matter — shouldn’t need to lug around the constant and heavy fear that rejecting people will cause them personal harm.

When internet communities rife with hatred turn toward misogyny and cyclical reinforcement of their own spiteful ideologies, the fear of rejecting even your own friends can be enough to silence you into passivity. Incel communities are starkly different from other frustrated people. These online communities start with a spark and then continue adding fodder until the flames of their detestation turn violent, sometimes canonizing figures such as Elliot Rodger, who murdered a number of people in 2014 on the University of California at Santa Barbara campus. Why wouldn't women be scared of such communities?

This doesn’t mean you owe your friends more than you’re willing to give them. It means the conversation surrounding the friend zone needs to be altered. Putting someone in the friend zone is a sign of honesty, not hatred, and should be coupled with respect, not violence. Human worth doesn’t grow on the basis of whether or not you can be in a relationship with them. A person should be valued because they are a person, and not because you think they could be your person.

Retaliations to rejection range from the abandonment of a friendship to the violent and cruel acts I mentioned above. The fear of these consequences needs to be eradicated, and that starts with dropping the assumption that people owe you what you want from them.

SOPHIA DUROSE is a College sophomore from Orlando, Fla. studying English. Her email is sdurose@sas.upenn.edu

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate