On Nov. 9, 2016 — the day after Donald Trump stunned the nation by winning the United States presidency — Houston Hall at the University of Pennsylvania was packed to the brim. That day’s University Council meeting, a routine administrative gathering of Penn’s student, faculty, and staff leaders, had become a hotly anticipated event.

Hours after Trump’s victory, the shock continued to echo throughout campus. Students eagerly attending watch parties had returned home in tears. Professors canceled their classes and postponed exams. Even the weather, chilly and overcast, seemed to reflect the mood of Penn’s largely liberal student body.

Everyone wondered how Penn’s administration — particularly, Penn President Amy Gutmann — would respond.

Gutmann had stayed almost entirely silent throughout the election cycle, other than a brief criticism of Trump’s proposed ban on Muslim immigration. Penn hadn’t released a statement after either of Obama’s victories, in 2008 and 2012, or after either of Bush’s in 2000 and 2004.

But Nov. 9, 2016 felt different. Trump and his family had direct ties to the University. The election had been unusually divisive, and people at Penn worried about the repercussions.

Undocumented students feared a repeal of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program; international students were concerned that Trump’s travel ban would cut short their education, and minority students worried that Trump’s often hostile rhetoric would normalize discrimination.

One student, speaking for the interfaith organization PRISM, burst into tears while delivering her statement at University Council that day. And in a rare, unrehearsed gesture of public affection, Gutmann stood up, click-clacked across the room in her heels, and gave the student a hug.

Yet, Gutmann’s official statement that day married the sober reality of the election with the sweeping Penn values that define all her public speeches. Asked if she would attend a solidarity march planned for later that evening, Gutmann declined, but promised to be there in spirit.

"This presidential campaign was one of the most bitter, divisive and hurtful in American history. Whoever won, millions of people were going to be terribly troubled by the results,” Gutmann’s statement read. “It is my hope that ideals that we hold dear at Penn — inclusion, civic engagement and constructive dialogue — will guide our nation's new administration, and that they will work hard to ensure opportunity, peace and prosperity for every person and every group that together form the diverse mosaic of the United States."

Gutmann’s decades of academic work in democratic theory, high-powered stint on a government commission, countless administrative initiatives to promote inclusion, and personal background as the low-income daughter of a refugee had brought her to this moment. How would she lead the University of Pennsylvania through an era when many of the values she stood for seemed under attack?

Since election night, Gutmann’s response has been, effectively, to walk a fine line, balancing between acting on her deeply liberal beliefs and leading a nonpartisan institution. Her administration releases statements at all the appropriate times, but some student critics find them tepid and perfunctory.

To this day, Gutmann has not mentioned Donald Trump by name.

It’s a dilemma any college president might face, but at Penn — both a leader in the higher education world and Trump’s alma mater — it has posed an unusual challenge for Gutmann.

* * *

Born in Brooklyn in 1949, Gutmann was a first-generation, low-income student when she first attended Radcliffe College. She ultimately earned degrees from the London School of Economics and Harvard University before beginning her career at Princeton University.

Today, with her face splashed across University pamphlets, it can be easy to forget Gutmann’s roots — as a scholar and a teacher. Before she became president of Penn in 2004, Gutmann spent decades in academia, working her way up Princeton's hierarchy while publishing well over a dozen books and countless papers.

Gutmann, a political theorist, has pursued many topics over the course of her academic career, but much of her work has explored the philosophical ideals of equality, democracy, and education. Her former colleagues describe her as a clear-minded, sharp scholar with remarkably consistent views that have neatly translated to the way she runs Penn.

“I have no doubt that her interest in political theory and her strong and focused interest in productive deliberations and the ability to compromise have influenced almost everything she’s done as president,” said former Provost Vincent Price, now president of Duke University.

Writing about the importance of compromise prepared her to handle the administrative wrangling involved in running a large research university; studying democracy and education informed her efforts to make Penn more inclusive.

By the time she arrived at Penn in 2004, Gutmann’s administrative skills had been honed by her time as dean of the faculty at Princeton and as provost of the university. But Penn — a conglomeration of centers, institutes, and graduate schools nested in a major city — would present a new challenge.

“When she decided to take that job she didn’t take it because she wanted to be a university president — she took it because she wanted to be at Penn,” said Charles Beitz, a Princeton professor who has known Gutmann since the 1970s.

Back then, the University of Pennsylvania was considered a good school, but lacked the strong undergraduate programs and the global prowess that set some of its Ivy League peers apart. “That moment, you sort of had the sense that Penn needed a strong leader, and that she was ready to be that strong leader — even if she was still growing into the job,” said William Burke-White, the director of the Perry World House, one of Gutmann’s special projects.

From her perch as president of an Ivy League institution, Gutmann has a certain platform in the world of higher education — and she’s chosen to take advantage of it. From 2005 to 2009, she served on the National Security Higher Education Advisory Board, a committee that advises the FBI on national security issues that relate to academia. In 2014, she was elected to a one-year term as president of the American Association of Universities. She also serves on the board of Vanguard, the National Constitution Center, and the Berggruen Institute in New York.

Most famously, in 2009, Gutmann was appointed by then-president Barack Obama to chair the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. In that role, Gutmann led nine experts from fields like philosophy, medicine, engineering, and religion in advising the White House on bioethical issues. Members of the commission consistently pointed to her consensus-building ability as a strong point of her leadership, especially when it came to notoriously divisive topics.

“There are too many people in academia who don’t live up to the ideals they write about,” said Daniel Sulmasy, a commission member. “But that’s not true of Amy Gutmann.”

* * *

At a time when campus controversies earn headlines several times a year, Gutmann has largely managed to steer Penn forward without entanglement in the violence or protests that have dogged schools like University of California, Berkeley, University of Missouri, Yale University, and Middlebury College.

Perhaps that can be chalked up to the makeup of Penn’s students — often more focused on networking and job-searching than on protesting and activism — but it also reflects the administration’s studious efforts to keep Penn out of the political spotlight.

Gutmann, in an interview with The Daily Pennsylvanian, explained that for her, Penn's freedom from serious political controversies goes back to its emphasis on free speech and inclusion.

"I’m sure that that [Penn's commitment to open expression] contributed absolutely, fundamentally, to why through the most turbulent times — which are not unique to today, I’ve seen them throughout my career — our institution of higher education not simply weathers the storm but gets stronger through it," she said.

The fact that the first Penn graduate to fill the Oval Office happens to also be one of the most divisive, controversial presidents in American history hasn’t made that easy. Though Donald Trump has shown little interest in Penn other than a tendency to boast about his Wharton credentials during rallies, his history at the school presents a quandary for administrators.

Without exception, they’ve chosen to avoid any mention of Trump’s history at the school.

Wellesley University devotes a special webpage to Hillary Clinton, Occidental College touts its connection to Barack Obama and Yale’s alumni magazine has published a feature about George W. Bush. In contrast, Penn only added Trump to a list of notable alumni a week before his inauguration, and only after a reporter asked why he was missing.

The reasons for Penn’s reticence are obvious. To many in the liberal-leaning, cosmopolitan, schooled world of higher education, Trump and his movement grate against everything for which universities are supposed to stand.

“There is no question that all of those things — reasoned discussion, democratic education and the public mission of public education, and democratic education, which have been national projects of huge importance — are all under threat, and all under fire like never before,” Princeton professor Stephen Macedo said. “It definitely requires sensible leadership.”

Unlike some other university presidents, Gutmann — a Democratic voter who hired Joe Biden to teach at Penn and whose husband has donated over $1,000 to Democratic campaigns, according to the Federal Election Commission — hasn’t taken many opportunities to publicly criticize the Trump administration.

Her public statements have largely hewed to issues — the travel ban, DACA repeal — that directly affect the Penn community. In both those cases, Gutmann condemned the policies and promised support to affected students, but did not mention the president himself.

And, in those instances, Gutmann’s actions were barely political. The policies would have directly impacted international and undocumented students at Penn, not to mention hampered Penn’s ability to attract worldwide talent for its research activities. The statements were less a forthright expression of Gutmann’s political views than a sensible movement to ensure the health of the University.

"When policies directly either contribute to or threaten our core values, I speak out," Gutmann said. "When they contribute to, I speak out in favor of them, and when they threaten, I speak out against. And the immigration ban and the executive order were examples of a threat."

Students seemed to agree that the danger posed by the change in immigration policy outweighed any need to be nonpartisan.

“The consensus was that this is not a political matter — because it’s a student issue affecting students on our campus, and it’s not just about if you’re a Republican or Democrat or what your political opinions are,” said 2017 College and Engineering graduate Riad Hamade, formerly the speaker of the Undergraduate Assembly, who served as the main point person facilitating communication between students and the administration during the travel ban controversy.

Gutmann’s influence is not limited to her public persona. She heads a university with a massive government and community affairs arm that has spent millions lobbying for favorable policies. And her connections to prominent Democrats are well-known.

“She knew all of the leadership of the country at that time,” said Raju Kucherlapati, another member of the bioethics commission. “Certainly I’ve seen her interacting with Vice President Biden at that time and I’ve seen her interacting with the Health and Human Services Secretary during that time — and they all know her, not just as president of Penn, but also as a person and they … were very admiring of Amy.”

Burke-White said Penn, more generally, has tried to handle the Trump era by creating space for dialogue about the thorny issues that have driven the country apart. The administration has even reached out to several White House officials, asking them to attend events at the University. But attracting Trump conservatives to an elite, coastal college can be difficult — none of them, he said, have made themselves available.

* * *

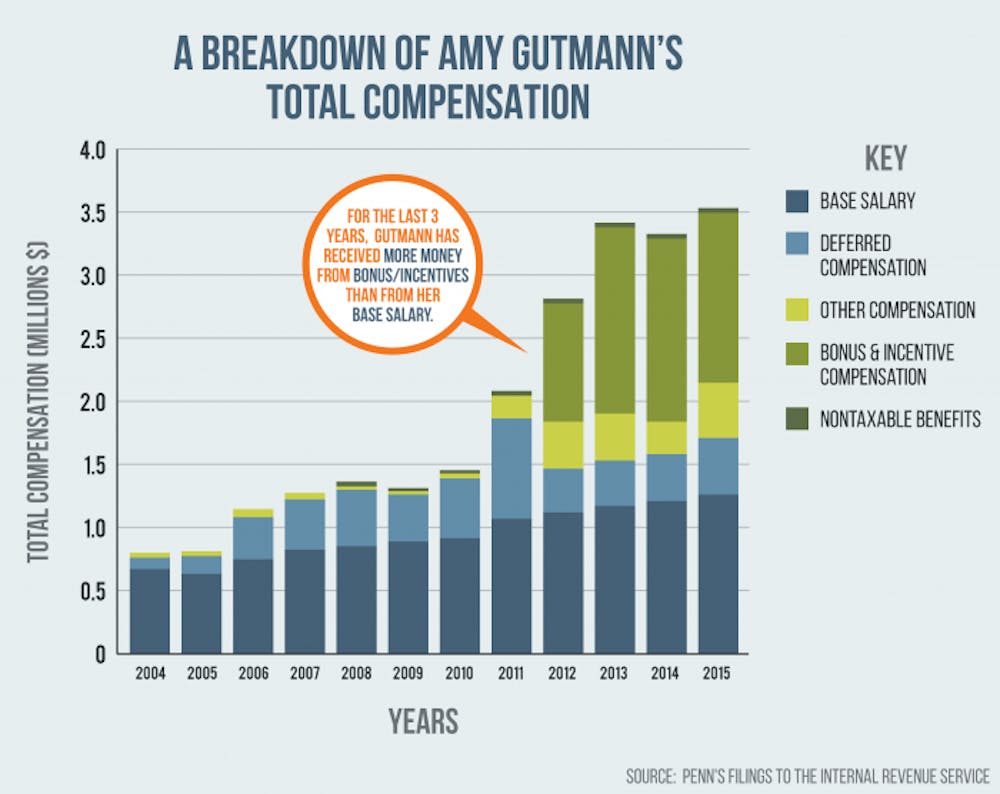

Gutmann’s 13-year presidency has had its fair share of successes. Fundraising prowess, a raft of new initiatives and projects, and Penn’s rising status in the Ivy League all suggest that Gutmann's academic aptitude has translated well into administrative skill.

But for the average Penn student, Gutmann can be a somewhat distant figure. Students see her at the milestones of their college careers, convocation and commencement, with a few public appearances sprinkled in between. Between juggling all the demands of her presidency — dozens of schools, centers, and a major hospital — and forging and maintaining connections outside the University, Gutmann has little time for the one-on-one interactions that students crave.

When a student dies or a political event rattles campus, students want their school’s leader to show she cares. And often, Gutmann is the only University leader they know and recognize.

“Sometimes I think that’s the issue: that students expect President Gutmann to be able to respond immediately and effectively,” said 2017 College graduate Kat McKay, a former president of the Undergraduate Assembly. “Those people fundamentally misunderstand how the administration works.”

In private, administrators, former colleagues, and students describe Gutmann as thoughtful, engaging, and supportive. When she talks to you, you feel like you have her entire attention, no matter how busy she might be. That translates into birthday wishes, Christmas cards, snacks for students at meetings, little reminders that Gutmann’s lofty position hasn’t stopped her from caring about ordinary people.

“I think that she’s someone who’s very personable. She definitely also gives you the impression that if she’s taken the time to sit down with you, then she’s seriously listening and internalizing what you’re saying,” said College senior Krisna Maddy, chair of the United Minorities Council. Maddy and other 5B minority coalition group leaders have met with Gutmann to address issues like faculty diversity.

But, unlike other Ivy League presidents, Gutmann does not hold office hours. Events she does hold with students don’t always offer the chance to engage with their president directly.

During a “campus conversation” in November designed to address the contentious issue of mental health, Gutmann shared personal anecdotes but did not take any audience questions. She only responded to queries that had been submitted in advance by Undergraduate Assembly President and College senior Michelle Xu, who moderated the event.

Some student groups, particularly those seeking more radical change at Penn, have grown frustrated by what they see as the administration’s complacency.

Fossil Free Penn, which has spent years lobbying the University trustees to divest from fossil fuel-related investments, staged a dramatic sit-in last year that eventually forced Gutmann and Chair of the Trustees David Cohen to meet with student activists.

“To be honest, it didn’t seem like a really collaborative discussion," said College junior Zach Rissman, who is Fossil Free Penn’s co-coordinator. "It more seemed like we were bringing points up to President Gutmann and Chair Cohen, and they were just repeating what they had been saying from the beginning."

Ph.D. student Nick Millman, who helped organize a work-in to protest a version of the House of Representatives' Republican tax bill that would have imposed taxes on graduate students, was unsatisfied with Gutmann’s email pledging support. He noted that other university presidents had taken action more decisively against the bill by sending representatives to protest against it at senators’ offices.

“While there are things being voiced, it’s not enough,” Millman said. “It’s not backed up with deliberate or concrete action that could be taken.”

To be fair, Gutmann’s forays into activism haven’t always gone well. Famously, Gutmann’s participation in a "die-in" to protest police brutality during her annual holiday party resulted in immediate backlash from Penn’s Division of Public Safety. The incident illustrated a timeless struggle every university president faces: Make your views too strongly known, and you’ll always alienate someone.

* * *

Late last year, Gutmann’s contract was renewed until 2022, making her the longest-serving president in University history. Though nearing her 70s, Gutmann’s energy seems boundless as ever.

Gutmann’s connections to the former Obama administration and prominent Democrats, along with her administrative credentials and political background, raise an obvious question. Would she choose to serve in government again?

For the time being, it seems unlikely — especially in today's political environment.

“She certainly would be very capable but I think she’s also very at home in educational institutions — I think she’s really found the places where she can contribute the most,” Macedo said.

Penn President Amy Gutmann, pictured here, celebrates the opening of Perry World House, the new recipient of nearly half a million dollars in grants from the Carnegie Foundation.

If Gutmann did enter government, said Christine Grady, another member of the bioethics commission, it would likely be something high-level, where she could continue to play the part of the “visionary she is."

“Anything that’s too bureaucratic, she would hate,” Grady said.

For a scholar of political philosophy, especially one who specializes in the ideals of compromise and reasoned deliberation, the current state of the U.S. government looks pretty bleak. A priority for Gutmann right now is making sure younger generations are prepared for the partisan tumult that seems like an inescapable part of public service.

For now, Gutmann says, she's happy on the outside.

"I worry that the ongoing gridlock can discourage people, good people, from going into public office," she said. "But I, myself, have found my calling, and for the foreseeable future, Penn is my calling."

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate

Most Read

More Like This