In recent years, as various universities have stepped forth to acknowledge early institutional ties to slavery, Penn has remained steadfast in asserting that it does not have a history of direct involvement with slavery or the slave trade. Now, new undergraduate research places this assertion into doubt.

An independent student study, supported by Penn's History Department, has found that many of the University's founding trustees had substantial connections to the slave trade.

After Georgetown University openly acknowledged its own ties to the slave trade in 2016, many colonial universities were placed under pressure to re-examine their own history with slavery. At the time, Penn Director of Media Relations Ron Ozio told The Philadelphia Tribune that “Penn has explored this issue several times over the past few decades and found no direct University involvement with slavery or the slave trade."

However, throughout the course of last year, student researchers who were part of the Penn History of Slavery Project discovered that out of Penn's 28 founding trustees who were investigated (there are 126 founding trustees in total), 20 of them held slaves between 1769 and 1800 and had financial ties to the slave trade. The group has not found evidence that the University, as an institution, owned slaves.

These ambitious efforts to confront Penn's colonial past were spearheaded by College seniors Caitlin Doolittle and VanJessica Gladney, 2017 College graduate Matthew Palczynski, and College sophomores Dillon Kersh and Brooke Krancer, who is also the social media director at The Daily Pennsylvanian. These students worked closely with History professor Kathleen Brown for the preliminary research study.

The group presented their preliminary research on Dec. 11 at College Hall only weeks after the Princeton and Slavery Project unveiled dozens of archival documents about Princeton's ties to slavery. Like the research being done at Penn, the Princeton and Slavery Project was a "bottom-up affair" that originated from undergraduate research, The New York Times reported.

The students at Penn focused their research on early trustees like John Cadwalader, Joseph Reed, and the first Provost of the University William Smith.

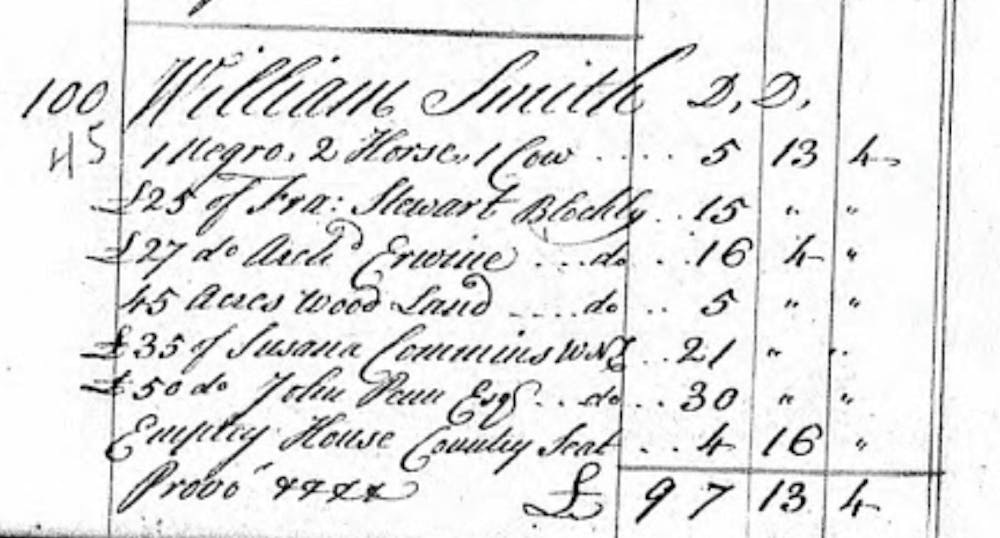

Many of the most prominent trustees were found to have substantial connections to slavery. Based on a 1769 Pennsylvania Tax and Exoneration form found by student researchers, Smith, who became Penn's first provost in 1755, owned at least one slave along with farm animals and over 40 acres of land.

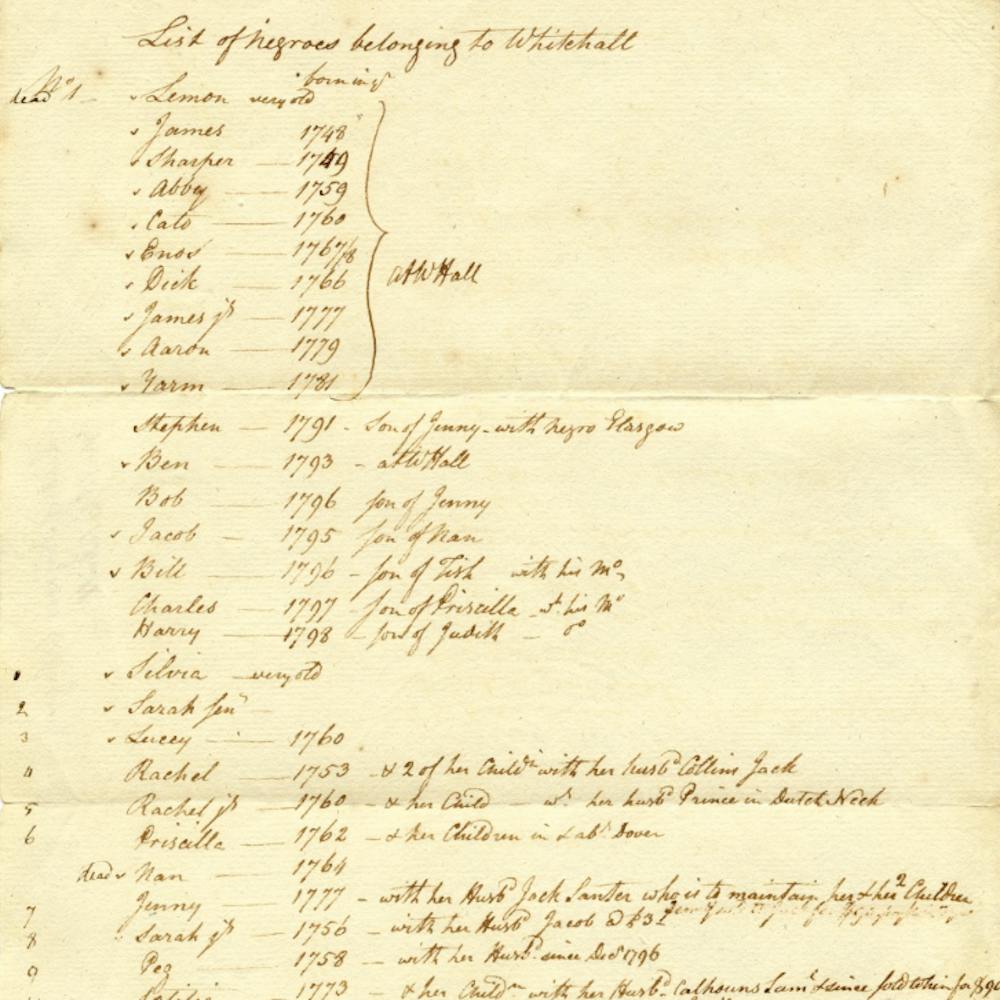

Philadelphia lawyer and Penn Trustee Edward Tilghman Jr. owned a number of slaves on his Delaware property, called Whitehall Plantation, according to a kept record of the plantation.

Brown explained that the group's research provides new, important insight into Penn’s connections to slavery.

“Penn as an institution has not thought, itself, about having a deep history of involvement in slavery,” she said. “These findings suggest that view might need to be altered.”

During an initial request for comment, Ozio said he would "reserve comment" until after a Jan. 12 meeting arranged between the research group and key members of the administration, including Provost Wendell Pritchett and Senior Vice President Joann Mitchell, who was named Penn's first chief diversity officer in March last year. However, Ozio subsequently did not respond to requests for comment both before and after the meeting.

Students said that at the meeting with administrators, they spoke about their future research plans at Penn and went over recommendations they had for the University in light of the findings of their research. Among other recommendations, students encouraged administrators to retract the University's original statement denying Penn's ties to slavery.

Students also told Pritchett and Mitchell that the University should be more transparent about early trustees’ ties to slavery.

In a speech this year, President of Harvard University Drew Faust publicly stated that Harvard had been "directly complicit" in slavery, The New York Times reported.

“Only by coming to terms with history can we free ourselves to create a more just world,” she added.

In an interview before the meeting, Kersh argued that Penn is still complicit in colonial slavery even though students have not found evidence that the University itself owned slaves.

“Penn’s early trustees were the wealthiest people in Pennsylvania,” Kersh said. “Their personal ties to slavery is definitely something that the University is responsible for regarding the financial backing of the University.”

Moving forward, the group wants to further their research by verifying more concrete connections between the University and the slave trade, such as investigating if slaves were involved in creating buildings on campus or if they were sold to fund the University.

Brown said this research was partially motivated by shifting perceptions on universities' ties to slavery across the nation.

In 2003, the former President of Brown University Ruth Simmons appointed the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice to uncover the university's historical ties to the slave trade. However, at the time, “there wasn’t a single peep from another university,” said James T. Campbell, the historian who led the Brown effort, in a conference last year.

However in recent years, that attitude seems to have shifted. And as of today, more than a dozen universities, including Brown, Harvard, and the University of Virginia, have acknowledged their historical ties to slavery.

College senior Matthew Palczynski speaks at a Dec. 11 presentation on preliminary findings of the University's connections to slavery.

During their research process, the group at Penn made visits to both the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the Library Company of Philadelphia to peruse primary sources including tax documents and wills. They also gathered information from online ancestral databases and were introduced to documents with the help of Mark Lloyd, the director of University Archives.

Yvonne Fabella, the associate director of undergraduate studies in the History department, said she was really impressed by the research that the students had done.

“It’s no small task to do the detective work and to gather the fragments of evidence into a rather cohesive story,” she said.

Students said they also felt proud of the results of their research.

“It’s a strange feeling of accomplishment,” Palczynski said about finding evidence during the research process. “The scholar in you feels good, but the human in you is like 'oh dang.'”

Though their study largely revolved around Penn’s implications in the slave trade, the group also wanted to humanize the experience of the enslaved people who emerged in their research. They plan on recruiting more student researchers to take on unanswered questions such as what the freed slaves did later in life.

“It’s really easy to lose sight of the humanity of the actual people who were suffering as a result of these systems,” Doolittle said.

“For me, that’s part of the reason why I felt like meeting periodically was very helpful … to be able to reaffirm as a group ‘we’re doing this because people suffered, because there are people who lived this experience who’s story we should be honoring,'” she added.

Gladney agreed.

“I love Penn and I love my University, but also history is very impossible to deny,” she said. “It’s sometimes hard to reconcile the two.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate

Most Read

More Like This