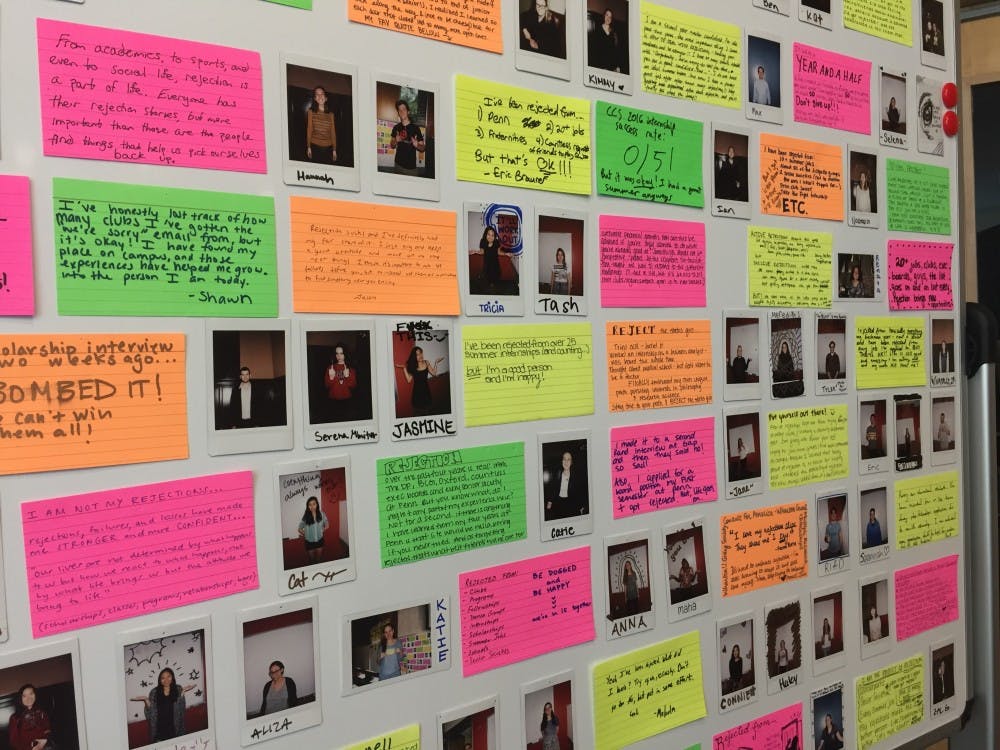

The 'wall' was the brainchild of College senior Rebecca Brown.

Credit: Joy LeeGROUP THINK is the DP’s round table section, where we throw a question at the columnists and see which answers stick. Read your favorite columnist, or read them all.

This week's question: Several students have started a "Wall of Rejection" project in the Annenberg School for Communication that aims to help students deal with rejection at Penn. What can Penn as a school — either on the part of the administration, faculty or students — do to help students better manage rejection?

James Lee | The Conversation

I actually had a wall of rejection in my high school, where seniors would put up rejection letters from colleges and perhaps write some not so nice things on them (Stanford had the nicest rejection letter — I almost forgive them). But this general issue of failure and rejection at Penn is is an extremely difficult one to talk about, as it directly relates to problems involving mental health. The fundamental issue — that Penn attracts mostly those who have generally succeeded in life — is an inherent part of what Penn is, and will never go away. Competition is the cause of these problems, yes, but the fact of the matter is that the privileges and opportunities afforded to us are there only because we have survived and thrived in such competitive environments.

I do think that the most important part of being able to endure in such a world is personal. You have to be able to view and consider yourself outside of what the world tells you. Yes, firms, schools and other institutions may view you as a number, a score, a resume, etc. But only we know the experiences that we have undergone, the difficulties we have overcome, the courage and grace we have displayed throughout our lives. Remember that. Take great pride in that. Have faith that these qualities will pull you through tough times, and that people will recognize them in the future, even if it isn’t happening right now.

Cameron Dichter | Real Talk

If we really want to help students better manage rejection we need to be honest about why they’re so afraid of it. And the answer — despite what many baby boomers would have you think — is not that millennials were all given participation trophies and now need constant affirmation. The truth is that, for all we talk about “the importance of making mistakes” and why “you must fail before you can succeed”, no one seems to really believe it. Or at least no one acts on it.

For many students the prospect of failure feels less like an opportunity to grow and more like a threat to their future.The reality of the job market is that you’re often competing against an array of nearly perfect candidates and therefore any small blemish in your record can make the difference between acceptance and rejection. One F can undermine a semester of A’s, one bad line in an interview can turn off an employer and even a single typo in your resume can be grounds for a rejection.

In a lot of ways this is a problem that goes beyond the scope of Penn’s campus but that doesn’t mean we can’t try to alleviate it. Two initiatives I believe could work are 1) decrease the number of courses with a forced curve and 2) allow students to retake courses to change their grade. Both of these plans would lessen the unnecessary burden that’s put on students to be perfect and thereby create a less stressful environment.

Emily Hoeven | Growing Pains

The "Wall of Rejection" project is one that I commend from the bottom of my heart. I honestly think that the best way to handle and manage rejection — and this applies to administration, faculty and students — is to talk about it, share stories about it, demystify it, destigmatize it. This is an issue about which I am very passionate — I co-founded the website PennFaces which aims to challenge the pervasive campus notion of the “Penn Face,” the façade of perfection and achievement many students feel pressure to maintain because they do not want to appear less put-together than their peers. The site collects and connects videos, photography and written stories that deal with perseverance and resilience. This is just one of many student-led initiatives that have launched in recent years in response to heightened awareness of and desire to improve Penn's hypercompetitive, pre-professional climate. The University's recent decision to expand CAPS' hours is another example of their recognition of the importance of talking things out. However, there are always improvements to be made.

Ultimately, I think all members of the Penn community — students, faculty and administration — need to be willing to talk about the challenges they faced or are currently facing on the path to "success." We need a hands-on, inclusive, encompassing approach. How great would it be to have successful professors, our University President or that one friend we have who seems perfect share stories about the difficulties and rejections they've faced in getting to where they are? We need to trouble the notion of "success" as something that is never built upon failure or rejection — we need to put forth the more complex and truthful narrative that all of us, at some point or another, in some way or another, will experience rejection. In sharing these stories, hopefully we will all come to see that rejection is not the end of the road, but rather part of a much longer process.

Shawn Srolovitz | Srol With It

From an academic perspective, Penn is a collection of some of the best and brightest students from around the world. Many Penn students come from the top of their classes and have never seen a grade below an A before the start of college. When students get to Penn and get that first grade that’s less than perfect, they are shocked and don’t know how to proceed.

Preparing students for the abrupt transition from high school to Penn’s rigorous academic environment is the responsibility of all parties — faculty, the administration and other students. Faculty who teach courses that are generally geared toward freshmen can help to ease the transition by providing study tips and making themselves available to students who are struggling. The administration plays a role in disseminating the abundance of resources on campus to students who are struggling academically, from Weingarten to the Tutoring Center to general advising.

And most importantly, in my opinion, it is the responsibility of the Penn student body as a whole to engage in conversations, like the Wall of Rejection, about what failure looks like at Penn (and that it’s okay to fail). By being more open about failure and the other not-so-perfect parts of our lives, we can create a dialogue within the student body to ease the pressure that students face and help improve the general campus culture.

Taylor Becker | Right Angles

At Penn, rejection is pervasive. When students are turned away from Greek life, a club, a friend group or a sports team, there is no denying that it hurts. However, rejection is part of life. It makes us stronger and frames the way we deal with future failures and eventual success. In addition, the rejections we face in college are usually quite small compared to the "real world," and offer us great opportunities to practice managing failure.

That being said, there is nothing wrong with attempting to improve students' skills at dealing with rejection. What we do not need is a program from University administration. It would not do much good, nor would it be appropriate. The University provides excellent resources such as CAPS to help those people who are disproportionately impacted by these social pressures. What can do good is student initiatives such as reforming club recruitment, which is currently underway by the Undergraduate Assembly. Faculty can encourage students such as the Princeton professor who published his "CV of Failures." Organic, bottom-up responses are the best way to deal with issues such as this.

Reid Jackson | Common Sense

The idea that the school would ever be expected to help its students learn how to "deal with rejection" is ridiculous, and frankly the fact that we are using this week's Group Think to discuss it is a waste of ink.

We all get rejected. Rejected from jobs, rejected by a sports team, rejected by a club, rejected by investors, rejected by the opposite gender, rejected by our friends or, even in terrible circumstances, our families. It sucks. Sometimes we're just not good enough to get the things we want, or often the things we deserve.

But it is not the responsibility of our university, a billion-dollar organization with the objective to teach the next generation of world leaders and pioneer excellent research, to soothe our feelings after rejection rears its ugly head.

The school already, rightly and brilliantly, offers CAPS to help students who need help with their mental health, and therapy is an excellent way to deal with the kind of severe despair that life can often serve us. But when students suffer individual instances of rejection, or even a nightmarish period of rejection, it's unreasonable for us to expect the university to supply the kind of day-to-day support that our friends and family give us through tougher times.

Amy Chan | Chances Are

I think that the biggest thing Penn can do is try to create outlets for students to pursue what they love without worrying about success. As if the classes weren't hard enough, all the clubs and groups at Penn are so competitive, and students can often feel discouraged and put down at every turn. At the very least, Penn students should be able to join groups without having done the groups' activity for many years or without having an abundance of natural talent. Either the groups should be more inclusive of actual beginners, or more groups should be started that allow students to focus on pursuing their passions and not worry about the outcome. And in focusing on doing what they love and the actual act itself, they will forget the pain of rejection, feel as if they are flourishing and understand that what ultimately counts is enjoying what they are doing, and not whether they are the best.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate