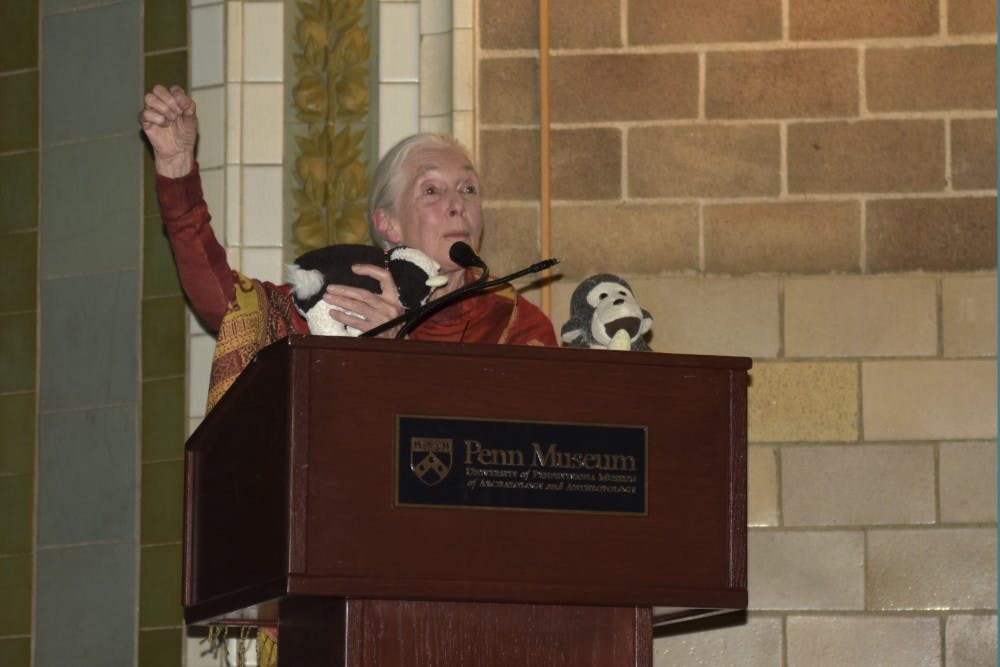

Primatologist Jane Goodall spoke about her work with chimpanzees at the Philomethean Society's annual oration on Thursday.

Credit: Jashley BidoThe wildest event at Penn Thursday night had to be the Philomathean Society’s Annual Oration. Excited students waited anxiously outside to get in, society members guarded the doors and speaker Jane Goodall greeted attendees with a traditional chimpanzee call.

The primatologist took the audience back 78 years ago to when she was a little girl with an insatiable desire to learn about and question the natural world. Goodall recounted that she would sometimes bring worms into her bed and even waited over four hours once to see how a hen laid an egg. Nevertheless, Goodall spoke about how lucky she was to have a mother who was so accepting of her love of animals.

“Isn’t that the making of a little scientist: Curiosity, asking questions, getting things wrong, learning patience,” Goodall said. “And to think a different kind of mother might have destroyed that.”

As the years went on, Goodall’s passion for animals continued to grow and at the age of twenty-three, she had the opportunity to assist paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey in a study that compared the behavior of chimpanzees to the behavior of humans.

At the end of this six-month journey to Africa, Goodall observed a chimpanzee whittling around a stick to make it smooth and eating termites with pieces of grass. The chimpanzee’s clear usage of tools was a huge discovery for the field because it showed a clearer link between humans and chimpanzees, Goodall said.

Goodall said she always likes to use this story to inspire young people to pursue their own passions.

“If you really want this thing,” Goodall said, “you are going to need to take advantage of things and work very hard.”

This message certainly resonated with many audience members, including College freshman Carlos Alcocer.

“We all have an opportunity and the resources, especially as Penn students, to make change,” Alcocer said. “I think she made that pretty clear that there’s so many institutions and so many resources and anything that you want to do, there are people that can help you.”

Goodall’s love for her work was also an inspiring take-away for a lot of Penn students. “She had so much soul behind her work,” College freshman Aiden Brossfield said. “Stereotypically, a lot of scientists are more brain than heart but she definitely has both.”

In her oration, Goodall further spoke about the choice between pursuing money and passion.

“I think it goes wrong when we start living for money,” she said. “Unlimited economic environment with finite resources is tragedy.”

“I liked how she talked about the unity between the mind and the heart and I like how she touched on consumerism and how we need money to live but we shouldn’t be living for money,” College freshman Helen Catherine Darby said.

Goodall also touched on the idea that while the immense human intellect separates the human race the most from chimpanzees, it can also be seen as a double-edged sword.

She discussed how things like global warming, nuclear weaponry and slaughterhouse conditions were all hurting humans, asking, “How is it possible that the most intellectual creature that inhabited human earth are also the one’s destroying it?”

This idea stuck with College junior Julia Wang.

“We normally frame things a lot as good or bad, in two binary extremes whereas she kind of put it in the context that they can coexist,” Wang said. “It’s important to understand that we can optimally push to do more good.”

Goodall also received the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology’s Wilton Krogman Award Thursday night. The award is an honor for individuals who are “pioneering and transformative of knowledge within the related fields of human evolutionary studies.”

One of Goodall’s messages was to get the audience members to use their intelligence for the better. The primatologist stressed the importance of remembering that an individual’s decisions impact not just themselves but those around them and those that come after them.

“There’s been a terrible disconnect between the human brain and the human heart,” Goodall said. “So often today, decisions are made without thinking about future generations.”

Yet Goodall concluded her speech at the Penn museum with optimism and goals that the human intellect can turn some of the world’s biggest problems around.

“My greatest reason for hope,” she said, “is the young people.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.