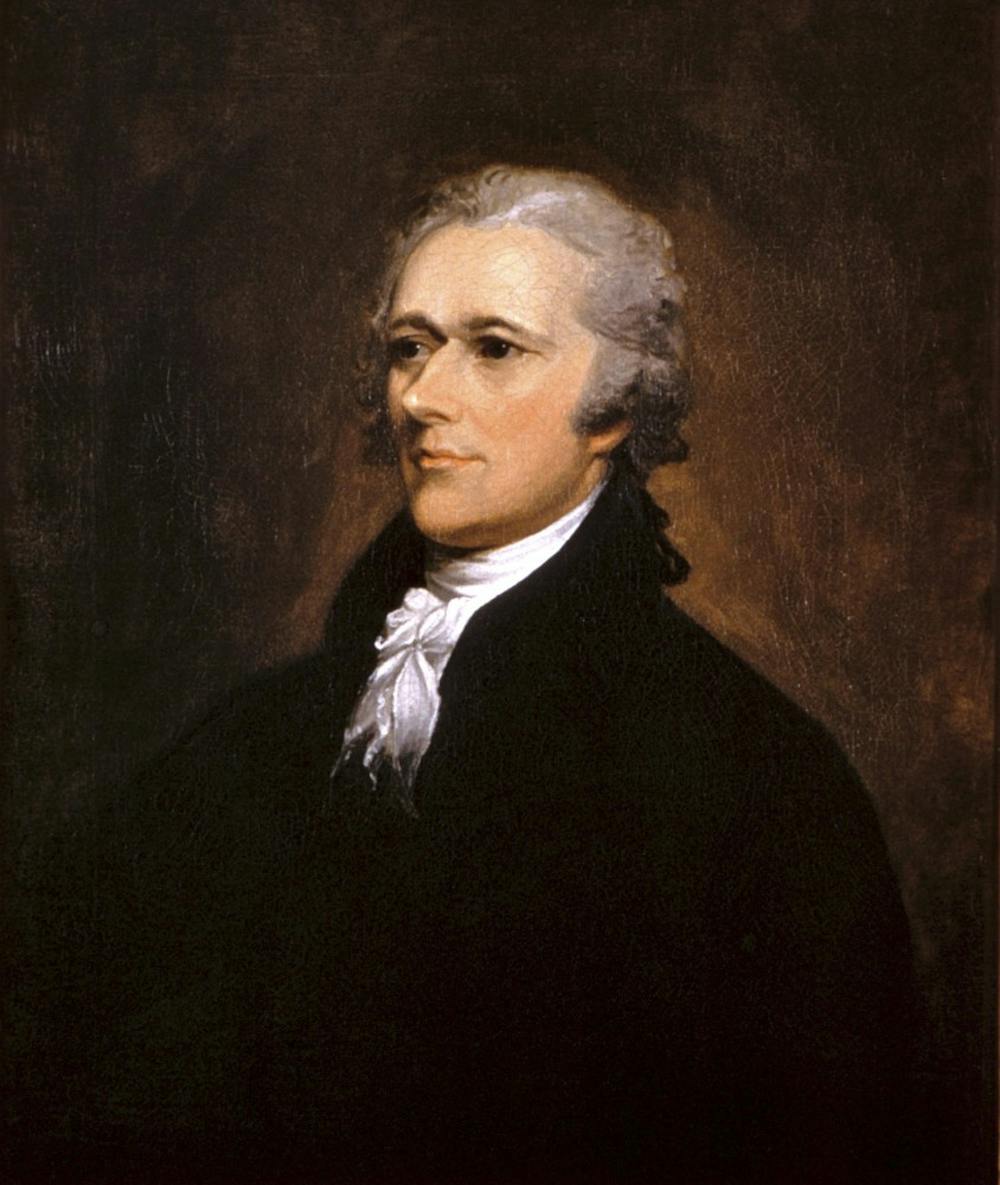

With the upcoming arrival of Lin-Manuel Miranda as the Commencement speaker, student interest in his musical, "Hamilton," has exploded. | Courtesy of Creative Commons/Wikimedia

Ever since the announcement of Lin-Manuel Miranda, the composer and star of the hit Broadway musical “Hamilton,” as this year’s Commencement speaker, Penn has been eager to embrace Alexander Hamilton’s legacy into the University’s history.

PennNews representative Amanda Mott wrote that Hamilton “evok[es] Penn’s own spirit, referencing rap lyrics such as ’I’m just like my country/I’m young, scrappy and hungry/And I’m not throwing away my shot.’”

While the city and Penn prepare to welcome Miranda, the Founding Father’s shadow looms in Philadelphia’s history. Through Hamilton’s political career, the nation’s capital was traded away from Philadelphia. Also at the hands of Hamilton, Philadelphia played host to one of the country’s first sex scandal.

While ascending to national historic importance, Hamilton traded Philadelphia’s then-almost-certain slot as the future nation’s capital city for a congressional vote.

On June 20, 1790, while facing tough political criticism, Hamilton, James Madison and then-Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson to keep the country’s future in tact, orchestrating what historians would eventually name the Dinner Table Bargain.

The famous bargain of 1790 forced the country’s leaders to choose a national city out of 16 potential options, according to PBS. At the time, Philadelphia, then the clear cultural capital of the country and the home of previous conventions, seemed the obvious answer.

The deal is also a significant plot point in Miranda’s musical, conveyed in “The Room Where It Happens.” The lines describe Hamilton “selling New York City down the river” as the nation’s capital in exchange for passing his debt plan. What the song ignores, however, is that Philadelphia was also a considered location of the capital. It is just one of several instances of Miranda’s musical glossing over Philadelphia’s crucial role in Hamilton’s political career.

“Hamilton trades New York for D.C. They don’t mention anything about Philadelphia, even though that’s what was actually on the table,” College senior Eli Pollock, who grew up outside Philadelphia, said.

“Ultimately, the whole musical takes small creative liberties ... It’s all for the sake for telling the narrative. It doesn’t really matter that it was supposed to be Philadelphia. It makes a better story that it was in New York, which is Hamilton’s own city.”

As they dined, the men moved toward agreement. In exchange for reducing Virginia’s tax responsibilities and Hamilton’s help pushing the Potomac plan through, Philadelphia was ditched in favor of the area near Virginia.

By the next month, the House of Representatives passed a bill now maintained by the Library of Congress, that made Philadelphia a 10-year capital until the creation of the permanent capital in Washington D.C. For a decade, the country’s top politicians would find a temporary home in Philadelphia.

When Hamilton moved to Philadelphia to begin working as the country’s first secretary of state, he settled on South Third Street, according to the country’s first census in 1790. Previously, he’d visited the city during the Revolution and the Constitutional Convention, but in 1790, he brought his young family and wife to stay.

It was also in Philadelphia that, in the hot summer of 1791, only months after Hamilton’s arrival, a young woman appeared at his door. Maria Reynolds was a married 23-year-old woman who needed help. Her husband had left her with a young daughter, and she desperately wanted to return home to New York. Taken with the young woman’s pleas, he vowed to financially support her. Later that evening, he would visit her home, prepared with government money.

When Hamilton arrived at the Reynolds house, young Maria invited him up to her bedroom, beginning a two-year affair.

For College freshman Hannah Spear, also a Philadelphia native, the musical’s coverage of the Reynolds affair brings to light a realistic depiction of the Founding Fathers, who are traditionally idealized in history courses. While she had always been interested in Broadway and history, and admired Miranda’s “In the Heights,” “Hamilton” was different.

“In the show, they objectify women; they cheat on their wives. That’s something that like, you wouldn’t learn in class,” Spear said. “You never hear about the bad qualities of the Founding Fathers. It’s just a really fresh perspective and a more realistic perspective.”

By the winter, Maria’s husband James had discovered his wife’s relationship with Hamilton. Rather than pledging divorce, he saw the opportunity to exploit the young politician’s secret, for the hefty sum of a $1,000.

The three developed a common understanding: In exchange for Hamilton’s hush money, Maria could invite the married father to her home when James was out of town. But by November the next year, James’ need extended beyond what Hamilton could provide, and he was arrested for forgery.

Enraged, James called James Monroe to his jail cell, where he promised to reveal information that could bring down Hamilton, his political enemy. After visiting Maria, who provided Monroe with incriminating letters, Monroe had them copied and, years later, the documents were ultimately leaked. In 1797, Hamilton published his “The Reynolds Pamphlet,” humiliating his wife and revealing his infidelity to the entire country while the Philadelphia press tarnished his name.

Through Miranda’s retelling of Hamilton’s story, the Founding Father has been a popular topic of conversation on campus.

College sophomore David DeLacoste-Azizi first listened to “Hamilton” in late August, after he heard friends from the theater community discussing the show at a social event. He was hooked immediately.

“It’s something I feel like a lot of Penn students relate to,” he said. “Alexander’s struggle in the musical is having a lot of ideas and not be able to make things happen as quickly as you want them to in the current system.”

Pollock agreed. “I didn’t listen to it until January, then I got really into it ... From the first listen on Spotify, I just thought it was one of the most well-written works of music I’ve listened to.”

Coming to college, only a 25-minute drive from his hometown, Pollock never thought musicals were his thing. He also never encountered much of the history of Alexander Hamilton and Philadelphia beyond a traditional trip to the Constitution Center.

“They do a fantastic job. Again, it’s not entirely historically accurate.” Pollock said. “But it makes for very intense story-telling.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.