Today, women account for 30.7 percent of Penn’s standing faculty, according to a University-wide survey conducted in 2011. This divide is far from even — but it was only within the last century that women were professors at Penn at all.

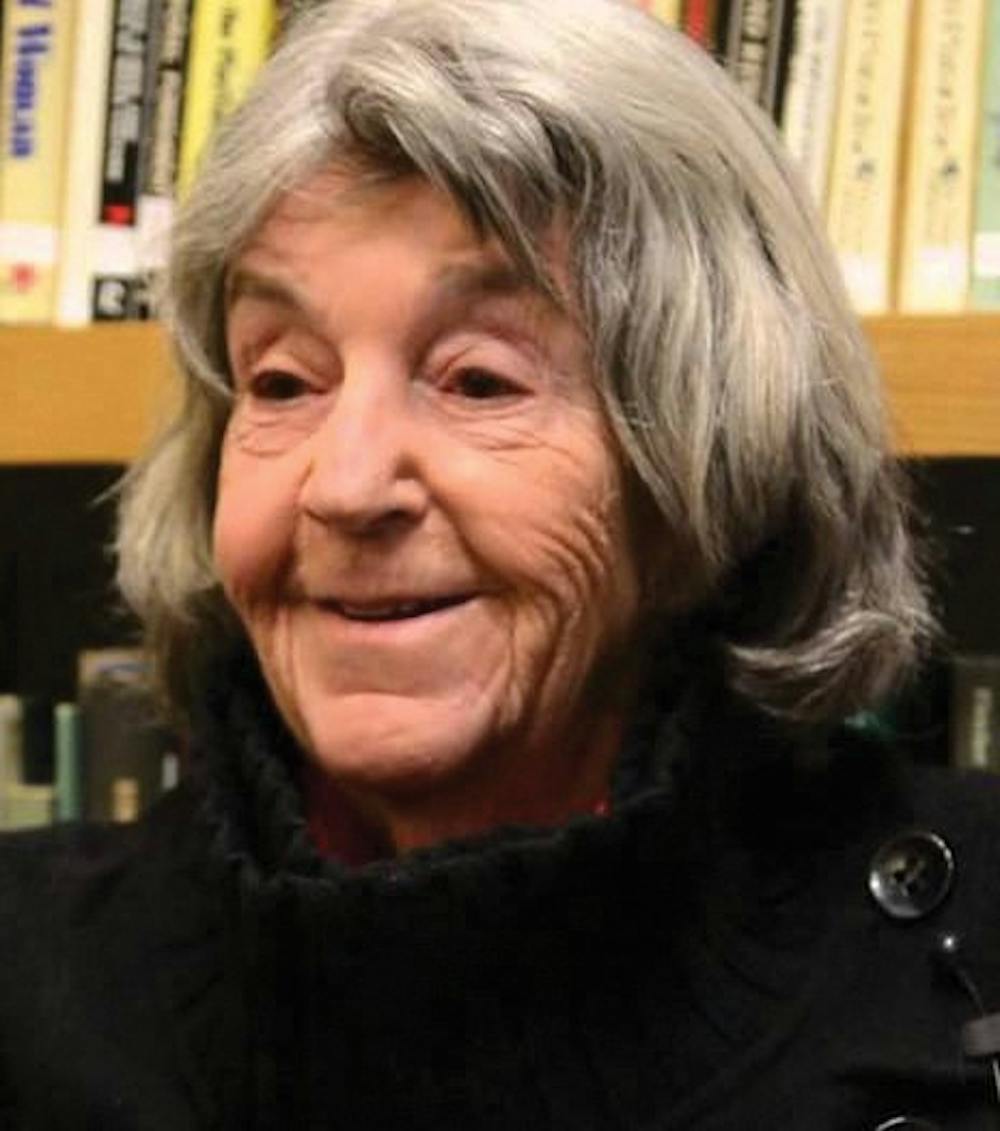

Conditions at Penn and academia in general have improved for women, but such progress did not come easily or without a fight. One of the women who helped open up opportunities for women in academia was Phyllis Rackin, a retired professor of English who teaches one course per year and first arrived at Penn in 1962.

At the time Rackin joined the English department, women were not being hired at other Ivy League universities, Rackin said, but Penn’s English department was looking to hire female faculty members.

“They had absolutely no women in the department,” Rackin said. Two other women were hired at the same time as she was. “So it was like I was in this special class of women.”

Rackin recounts some of the gender–based differences she encountered early on in her career at Penn, noting that all three of the new women faculty members had to share an office, while the men were two to an office — men and women were not allowed to share. And while women were limited to advising only female students, men could advise anyone.

Rackin remembered committee meetings, where there was a dress code requiring women to wear a skirt, pantyhose and pumps. During these meetings, she noticed that when a woman introduced a point, it would often be passed over by the other committee members. Minutes later, when a man would repeat the same idea, members would embrace it.

One of the most “flagrant examples of discrimination” that Rackin encountered was while she was part of the graduate admissions committee of the School of Arts and Sciences, which was chaired by a man who she called “notorious” for discrimination. “He would tell female students, ‘Why are you here? You’re taking up a place that a man could have,’” Rackin said. “He was pretty upfront with his misogyny.”

While the committee was reviewing applications, Rackin noticed that certain applicants were being passed over. When she inquired as to why, the chairman answered that they were women and just going to get married without doing anything with their degrees.

Despite these subtle and more obvious moments of discrimination, Rackin felt extremely lucky to have a job and said she was treated quite well. “They treated me sort of like their pet dog or something — in a kind of paternalistic, benevolent way,” she said. “The way you treat a token.”

In 1965, professor Robert Lumiansky became the new chair of Penn’s English Department. He had previously held top administrative positions at Tulane University and terminated the contracts of several women. When he came to Penn, he called all of the women in the department, except for Rackin, into his office and told them that their contracts were going to expire and that they would not be rehired. Rackin thinks she was able to keep her job because she was “sort of the ‘fair-haired girl.’”

Her luck ran out when she came up for tenure. On Nov. 4, 1969, a majority of the faculty in her department voted in favor of awarding Rackin with an associate professorship with tenure. Their recommendation then went on to higher-level administrators. But in February 1970, Rackin received a handwritten note from Lumiansky, which informed her that she would not receive a promotion and tenure.

“When the department voted for me, [Lumiansky] opposed it, and the people in the college personnel committee also opposed it because the chairman opposed it,” Rackin said. “There’s a lot of kind of crooked stuff that went on.”

Sensing gender discrimination, Rackin proceeded to file suit against the University with the help of a large law firm, now known as Pepper Hamilton LLP, who supported her case on a pro bono basis. Eventually, the University agreed to a settlement and granted her tenure.

“There were a few nutcases like [Lumiansky] who really had psychological problems about women. Most people had just sort of garden-variety prejudice,” Rackin said. “It’s like the difference between Donald Trump and your average man. Some men are obsessed with hating women, and some people just think they’re second-class citizens but are benevolent toward them.”

Rackin’s successful lawsuit opened the door for more women to move up the ranks in Penn’s English Department, but even now, decades later, Rackin believes that the statistics show that women still face challenges in academia. In the 2011 faculty survey, women were the minority group least likely to agree that their schools and departments made genuine efforts to recruit and retain women faculty. Forty percent of women also agreed to some extent that they had to work harder than their peers to be regarded as legitimate scholars.

“In general, I think that things have changed drastically for the better since the '70s,” English professor Melissa Sanchez said. “Unfortunately, however, women at Penn across all faculty ranks are still paid less than their male colleagues, and women are tenured, promoted and named endowed professors at a lower rate.”

The students in Rackin’s classes give her hope for the future. “I am so pleased at the young women at Penn right now. For a while, women students seemed to be really oblivious to feminist issues. [This] generation seems to be much more aware,” she said. “The students make me very optimistic about the future.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.