On Oct. 8, 2005, all that Penn football player Greg Ambrogi had to worry about was a slippery Franklin Field turf, and even that was working out in his favor. The Quakers were facing Bucknell in a pouring rain that only got worse as the game went on, and in the second quarter, Bucknell’s quarterback fumbled a snap. Ambrogi recovered the ball in the end zone for a Quakers touchdown.

As the rain picked up momentum, so did Greg’s older brother Kyle, a running back for the Quakers who notched two rushing touchdowns in the third quarter en route to an easy 53-7 Penn victory. Kyle had finished what Greg had started.

Two days later, Kyle fatally shot himself in the head in the basement of his mother Donna’s Havertown, Pa., home.

It took years for Greg to even be able to talk about Kyle, but in 2009 he joined his mother in founding the Kyle Ambrogi Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting suicide prevention and awareness of depression in young adults.

Still, Greg had planned to do more to promote depression awareness on Penn’s campus, discussing general mental health issues with his friend Justin Reilly, a 2011 Penn basketball graduate.

Then on Jan. 17, Penn track and field freshman Madison Holleran jumped to her death.

Greg knew it was his time to make a difference.

“So I thought to just go through the sports teams, alumni who have solid relationships with the coaches, get them on board,” he said.

Ambrogi and Reilly proposed to their former classmates a mentoring network of Penn athlete alumni to be a resource for current student-athletes.

The response was overwhelming. Reilly got 350 messages in his Facebook inbox in a span of 36 hours. Now more than three months later, Ambrogi and Reilly have set up a program of alumni mentors for nearly all of Penn’s 33 varsity sports programs and are still hoping to set up more. The pair officially launched the mentorship program last Thursday, putting a sign-up form on the homepage of the Kyle Ambrogi Foundation website.

But a day before the launch, Greg keeps looking back instead of ahead. Every question about the launch gives way to an answer about his brother. For Greg, the launch is his brother.

“I tried to have him get help,” Greg says. “A lot of friends talked to him like, ‘Hey, just talk to me! We’re best buds, we can talk!’ We didn’t know how to help.”

And now that he does know, he wants you to know how he learned.

‘Keep everybody together’

All through Mike Recchiuti’s senior season at Downingtown High School, he kept hearing about an outstanding running back from St. Joseph’s Prep.

“I was wondering to myself, who is this kid?” Recchiuti said.

It was Kyle, who ran for 322 yards and four touchdowns in a single game his junior year. Recchiuti, a 2005 Penn graduate, wound up a year ahead of Ambrogi, and when Ambrogi visited Penn with a group of recruits his senior year, Recchiuti gave him a tour of Penn’s campus.

“I thought that maybe he would be arrogant since he was such a standout player, but he was the complete opposite,” Recchiuti said. “When I told him that I had heard of him and what a great athlete he was, he sort of just shrugged it off and spoke of what the team had to do for the remainder of the season to accomplish its goals.”

Like Recchiuti, Ryan Pisarri, a 2006 Penn graduate, remembers Ambrogi being as generous as he was humble. Pisarri shared a townhouse with Ambrogi their senior year, and Ambrogi came in handy when he had to move in a couple of days before training camp started in mid-August.

“I drove up a truck with tons of clothing and furniture as I was preparing to get all settled in before camp started,” Pisarri said. “Kyle saw me outside and without hesitation came outside and offered his help.”

Ambrogi helped Pisarri move in until every piece of clothing was put away and every piece of furniture was set up a few hours later. Then, drenched in sweat, they walked across the street to Allegro’s.

“We just talked about anything and everything,” Pisarri said. “The upcoming football season. Senior year.”

But by then, Ambrogi wasn’t himself anymore. A month later, he told his mother, Donna, that he had thought about jumping off a bridge.

“We put him into counseling at Penn when we realized,” Donna said. “I don’t think he really understood what was happening to him.”

“We were in conjunction with Donna getting him help,” Penn coach Al Bagnoli said. “So he had medication and counseling. For the most part, everybody was seeing an improvement.”

Indeed, Kyle began taking notes in class and going out with his friends for beers again. But his suicide that October turned the Penn football program into a support group of 110 players plus coaches and trainers. Bagnoli invited CAPS staff members to talk to the team, also working with the Office of the Chaplain to encourage an open dialogue throughout the program. Bagnoli had one goal throughout the aftermath of Kyle’s suicide.

“Just keep everybody together,” he said.

“This situation was obviously so devastating, no one really knew how to handle it,” Pisarri said. “We all agreed that continuing to practice and playing was the right thing to do because Kyle would have wanted us to, but we had nothing left in the tank. Coach Bagnoli and his staff were an incredible support system and did everything they could to help us.”

Donna only started to definitively move on from her son’s death a few years later, when she began working with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. AFSP reached out to Donna to see if she’d be interested in participating in the organization’s annual International Survivors of Suicide Day activities. She accepted the invitation.

“The thing that impressed me with AFSP is they do research on the whys,” Donna said. “How did this happen? Most people involved in the organization have had a suicide somewhere in their life. So they get it.”

Encouraged by her work with AFSP, Donna established the Kyle Ambrogi Foundation in 2009. Since then, the foundation has sponsored need-based financial aid scholarships at Penn and St. Joe’s Prep. The foundation has also held a Beef and Beer event each year since then to raise money for AFSP.

“People make thoughtless decisions because they’re emotionally feeling so terrible,” Donna said. “But it’s scary, and you need help to work through that. And that’s part of the problem is you feel worthless. They think they’re not worthy of being helped. That’s tough to get through.”

‘Sign me up’

Greg got through by helping out with the foundation and trying to understand more about clinical depression. So when Reilly came up with the idea of setting up several alumni from the last 10 years or so to be mentors for each varsity program, Ambrogi was ready to act.

“Greg had tremendously more knowledge and connections than I did, so when we said, ‘OK, what does this actually looks like?’ he made a lot happen,” Reily said.

Each program mentor will undergo mental health training. Reilly and Ambrogi hope that mentors who have already signed up, as well as those still looking to find out more about the program, will show up for a Mental Health Awareness Day event slated for May 4, at a time and place on campus to be determined. The event will be run by Cogwell UPenn, a mental health group on campus.

Ambrogi and Reilly also want program mentors to be in contact with their mentees on a weekly or biweekly basis by text, and by phone at least once a month.

“The mentor shouldn’t be somebody that the kid’s going to call every week and be told, ‘Hey, I had a quiz in Spanish,’” Reilly said. “It’s just, ‘How are you feeling?’”

“We want people that really feel strongly about this and are willing to put in a couple hours of training,” Ambrogi said.

That approach has weeded out the vast majority of alums initially interested in helping out. But not Kyle deSandes-Moyer.

A 2013 Penn field hockey alumna, deSandes-Moyer went to Parkland High School, where as a freshman she became acquainted with future Penn football player Owen Thomas, a senior at the time. When deSandes-Moyer came to Penn in 2009, Thomas reached out to her and made sure college was going well for her. Often they would talk while walking to classes together.

After Thomas committed suicide on April 26, 2010, deSandes-Moyer was suddenly surrounded by grieving friends from both high school and college. The next year, five members of deSandes-Moyer’s class quit the field hockey team. The grief and stress were mounting, and deSandes-Moyer’s parents made her go to CAPS, where she says it was difficult just to secure an appointment.

“The doctor didn’t seem to understand the commitment I had to athletics fully and made suggestions that just weren’t feasible,” deSandes-Moyer said.

Eventually, deSandes-Moyer sorted out her mental health issues with the help of friends, teammates and parents. But her mental health experiences primed her for the call she got in February from Penn field hockey assistant coach Katelyn O’Brien telling her about Ambrogi and Reilly’s program. O’Brien, who had been good friends with Kyle Ambrogi, recommended deSandes-Moyer as the program point person for Penn field hockey.

“I was like, ‘Sign me up!’” deSandes-Moyer said.

By that point, Ambrogi had already reached out to a cadre of Penn coaches and, just as importantly, Jay Effrece, who works in the sports medicine department of Student Health Services and was a trainer for Penn football during Ambrogi’s time with the team. Effrece put Ambrogi in contact with CAPS, and Ambrogi met with CAPS Director of Outreach Meeta Kumar earlier this month for training advice.

“It will be very useful to have a mentoring point person for each varsity program,” Kumar said.

According to Kumar, CAPS has formal and informal training opportunities for Penn coaching staffs focusing on signs and symptoms of distress, referral strategies, information about CAPS services and a liaison relationship with CAPS senior staff. Ambrogi also recalls a popular Penn football mentorship program that focused on securing networking and job opportunities for current players.

Still, Ambrogi hopes that the new mentorship program will provide a unique opportunity for Penn student-athletes to voice mental health concerns.

“If you’re feeling bad about yourself or you’re not confident, the last people you’re going to tell are your coaches or someone trying to get you a job,” Ambrogi said.

Ambrogi would like the mentorship program to eventually extend beyond Penn Athletics and has targeted fraternities and sororities about providing mentorship opportunities there as well.

For now, though, the focus is on personalizing mentors for Penn athletes as much as possible.

“The hope would be, say on the basketball team, Justin [a Dallas native] could maybe mentor somebody from Texas who might have come to Pennsylvania and feels out of touch with what they’re used to,” Ambrogi said. “We can connect people to alums they have more in common with so they’ll be more willing to open up to that person.”

Reilly would be happy to be that mentor, as he proved when he talked to both the men’s and women’s basketball teams in February about mental health concerns.

“Essentially what I said was if anything matters, then everything matters,” Reilly said. “You matter. Everything that you do matters. People look up to you, people are inspired by you. No matter how you feel right now, whether it’s good or bad, there’s always more than that.”

Being together

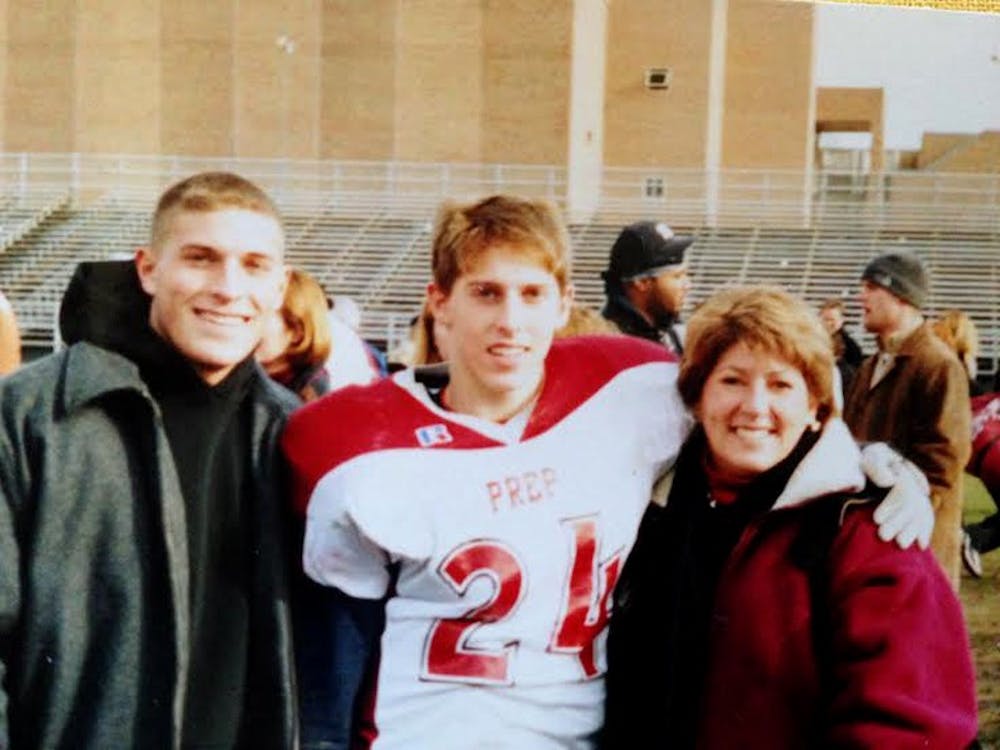

“Prep’s Ambrogi runs all over O’Hara: ran for 322 yards,” reads the Delaware County Daily Times headline inside the glass case. Two Philadelphia Inquirer stories on other successful games from Kyle Ambrogi’s days at St. Joe’s Prep run alongside another newspaper brief from Jan. 16, 2002, reporting Ambrogi’s declaration for Penn.

A teammate of Kyle’s from St. Joe’s Prep walks by and looks at the glass case full of his yellowed newspaper clippings.

“That’s Ron Jaworski,” he observes with a prideful smile, pointing to a photo of the former Philadelphia Eagles quarterback with Kyle while he was in high school.

But tonight isn’t about the past. Tonight’s about being together.

It’s the sixth annual Kyle Ambrogi Foundation Beef and Beer event at at the Great American Pub in Conshohocken, Pa. Kyle’s friends and family walk by in abundance, beers and sandwiches in hand. Florida’s beating Dayton in the NCAA men’s basketball tournament on the big-screen plasma TVs lining the bar, and DJ Tommy Tunes is blasting out Chicago’s “25 or 6 to 4.” Signed Adrian Peterson and Connor Barwin jerseys attract attention in the next room, but less so than a signed copy of Sports Illustrated with Kate Upton on the cover.

465 people are here in total to participate in auctions and raffles benefiting AFSP. About as many folks were here last year. They’ll be here next year too.

“Having a support system of people surrounding you is very important,” Donna said. “I’m very fortunate to have a large family, lot of friends. Penn family, Prep family, everybody.”

A “Penn players basket” donated by Penn football sits in the corner. It’s stuffed with a visor, a sweatsuit, a dri-fit T-shirt and shorts, each a reminder that once a teammate, always a teammate.

“You have to realize, being on a sports team is like having a family,” deSandes-Moyer said.

Nine years after his brother Kyle’s death, Greg’s greatest hope now is making that family feel a little closer.

“I want to see how I can be a helpful ear,” Greg said. “You can always do something more.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.