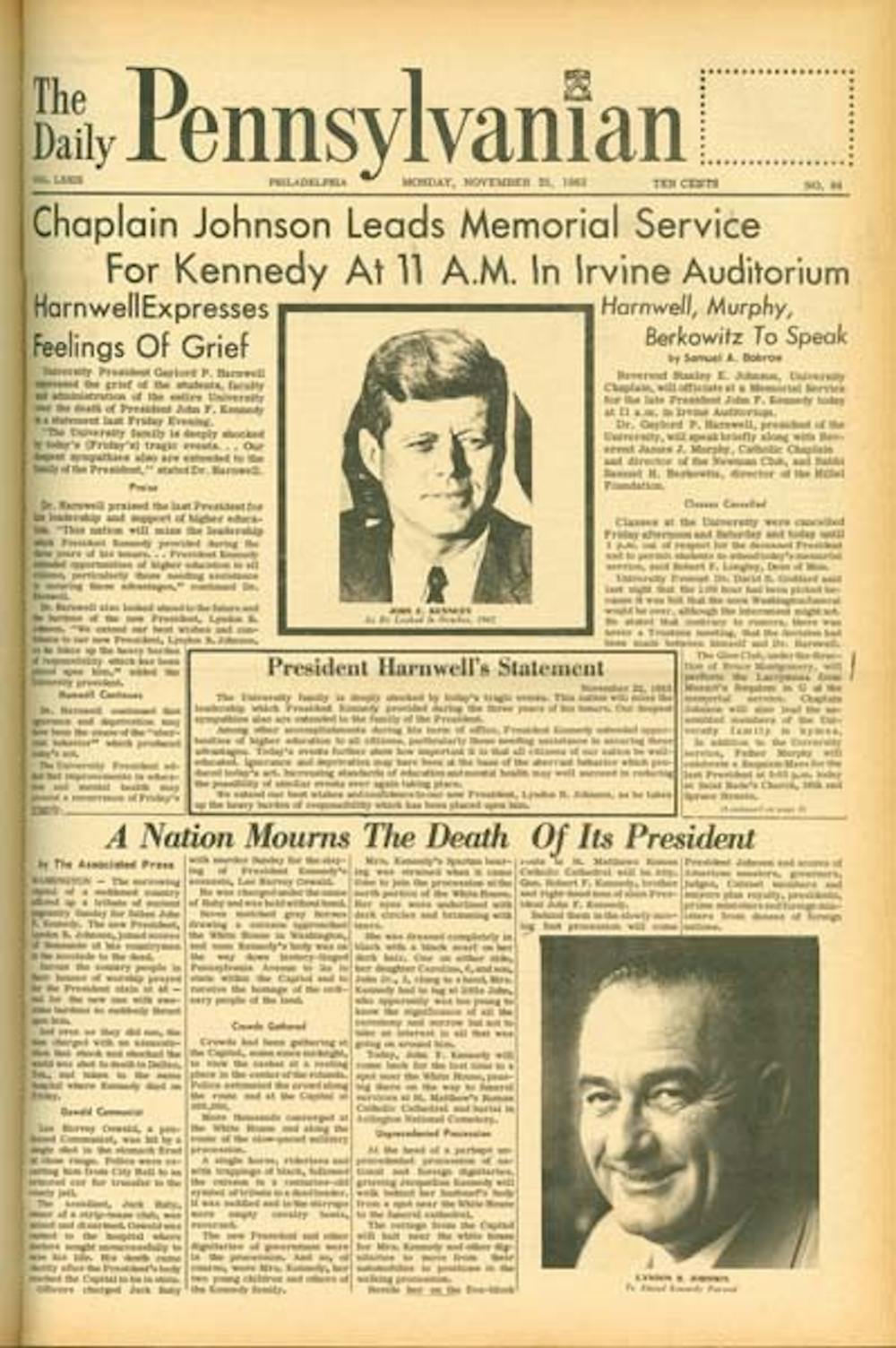

The front page of the first Daily Pennsylvanian after Kennedy’s death was devoted entirely to the former president.

Credit: Courtesy of University Archives and Record CenterAs the president’s motorcade rolled through the Dallas streets minutes before 12:30 p.m. on Nov. 22, 1963, Vicki Bendit sat with her grandmother in the living room of the family’s Huntingdon Valley home.

Back on campus, Bourne Ruthrauff had just started eating lunch with Gaylord Harnwell, Penn’s president at the time. Marc Ross, Ruthrauff’s friend and the managing editor of The Daily Pennsylvanian, was out on Hill Field, practicing for a football game scheduled for later that weekend between the newspaper’s news and sports departments.

George Weiss was sitting in class. Andrea Mitchell was somewhere inside the building that is now Hill College House, where she lived freshman year. Howard Marlowe was working on the first floor of Houston Hall.

Thousands of miles away, Bruce Kuklick, then on a graduate fellowship in England, had just finished saying a Latin prayer — a tradition before the start of every dinner at his University of Oxford dining hall.

It was 50 years ago, but each of the seven Penn alumni remembers what happened next — in the minutes, hours and days that followed — with an emotional and cinematic clarity that no camera can replicate.

They can still picture Walter Cronkite laying his black-rimmed glasses down on the table in front of him, fighting off tears as he told the nation that their president, John F. Kennedy, was dead; they remember Lyndon Johnson being sworn in as president on a crowded Air Force One, his right hand raised in the air as Jacqueline Kennedy, still wearing the blood-stained pink suit that she had on when her husband was shot, stood to his left.

They still picture Black Jack, the riderless horse, walking slowly down the middle of the street at the president’s funeral procession. And they still see little John-John, the president’s son, giving his father’s flag-draped casket one final salute as it was carried out of St. Matthew’s Cathedral.

“I think all of us who lived through those days felt it, and remember it today, profoundly,” Mitchell, now the chief foreign affairs correspondent for NBC News, said. “America was never the same.”

***

It had to be a dream, Vicki Bendit told herself.

Maybe the president’s motorcade was still making its way through the Texas city streets.

Or maybe the reports coming out of Dallas would turn out to be wrong.

This couldn’t be happening, she said. Not to Kennedy. Not to the country.

In high school, Bendit, a 1965 College graduate, had volunteered on Kennedy’s campaign against Richard Nixon. She handed out pamphlets, wore buttons and went door-to-door for the then-Massachusetts senator; her connection to Kennedy, she said, made his death especially difficult to bear.

“I remember thinking all day to myself, ‘Why would anyone want to do this?’” she said. “I think that question still goes through a lot of our minds.”

Bendit was with her grandmother in Huntingdon Valley as she watched the scene in Dallas unfold 50 years ago. As soon as Walter Cronkite told the nation that the president was dead, she knew that she had to return to campus.

As Bendit, dressed in a pair of jeans and a black turtleneck sweater that day, drove on the highway, gone was the usual Friday afternoon rush hour traffic. It was as if all of the cars around her were sleepwalking, she said — caught in a stupor that enveloped the country for days.

When she arrived back on campus, she said, the scene around her looked as if somebody had put a black filter on top of a camera lens. “People were walking around like zombies,” Bendit, now a semi-retired jeweler, said. “You knew that it had happened, but it was all still so unreal and unbelievable.”

That following Monday, Bendit was among the more than 2,000 students who attended a campus memorial service for Kennedy in Irvine Auditorium. The University canceled classes Friday afternoon and Monday; some professors decided on their own to cancel classes on Tuesday and Wednesday.

One of Bendit’s most vivid memories from the days following the assassination is going to a Saturday evening performance at the Academy of Music in Center City, where the Philadelphia Orchestra played two pieces: Bach’s “Come, Sweet Death” and Beethoven’s “Eroica” symphony.

Bendit, among dozens of Penn students who went to the performance, watched the orchestra play from high above, in the concert hall’s $3 nosebleed seats.

When the music stopped, nothing but silence surrounded her.

***

George Weiss grew up in Brookline, Mass., less than 100 yards away from Kennedy’s birthplace.

Weiss, a 1965 Wharton graduate and a member of Penn’s Board of Trustees, remembers attending a rally for Kennedy at the Boston Garden on the final day of the 1960 presidential campaign. Growing up in Boston, Weiss said he always felt a special connection to Kennedy.

On Nov. 22, 1963, Weiss was first told by a city garbage man who was working on 39th and Walnut streets that the president had been shot. He had gotten out of class minutes earlier, and the news hit hard.

“When you’re 20, 21 years old, you think at times that you’re invincible,” Weiss said. “That day really brought us back to earth.”

For the next six hours, Weiss sat in the living room of the Kappa Nu fraternity house, his eyes glued to the television screen as reporters in Dallas and Washington tried to piece together what had happened earlier that afternoon. Weiss doesn’t recall crying himself, but he does remember looking on as Cronkite’s voice wavered when he first reported Kennedy’s death — now one of the most iconic moments from the former anchor’s career.

“What he did was show the emotions that we weren’t showing yet,” Weiss said. “That was powerful.”

***

Before Kennedy’s assassination, Andrea Mitchell, the NBC correspondent, thought she would one day become an English professor.

Soon after the president was killed, she decided on a new career path: broadcast journalism.

Kennedy’s death in November 1963 was tragic, Mitchell said, but it was also transformational.

It was transformational on Penn’s campus, where Mitchell, a 1967 College graduate, remembers students packing into the Hill lounge that Friday afternoon, many of them crying as they watched the events in Dallas unfold on television. After the president was pronounced dead, Mitchell walked over to the studio of WXPN, a student-run radio station that was then located inside Houston Hall. Recognizing that they weren’t in a position to cover the events in Dallas, the student broadcasters decided to play Beethoven’s “Funeral March” for the rest of the day.

Kennedy’s assassination, she said, also transformed the national media landscape. “It was really the first event that gathered Americans around the television like that, the same way that Americans gathered around the railroad tracks to watch the Lincoln funeral train,” she said.

By showing firsthand the power, vividness and immediacy that live images on a television screen could have, she said, the Kennedy assassination played a large part in opening the door for aspiring broadcast journalists like herself.

Mitchell has been contributing over the past week to NBC’s Kennedy assassination anniversary coverage. “To this day,” she said, “as I’ve been reporting the anniversary on and off the air, I find myself crying again.”

***

“Chaplain Johnson Leads Memorial Service For Kennedy at 11 a.m. In Irvine Auditorium.”

“Harnwell Expresses Feelings of Grief.”

“A Nation Mourns The Death Of Its President.”

The headlines of the Monday, Nov. 25 edition of The Daily Pennsylvanian captured the collective grief of a campus that, for days, did not know how to react to the death of the nation’s president.

Bourne Ruthrauff, the DP’s editor-in-chief in the fall of 1963, had just sat down for a group lunch with Gaylord Harnwell when he heard raised voices coming from the Perelman Quad. When he first received word of the shooting, he, along with Marc Ross — the managing editor who had been playing football on Hill Field that afternoon — rushed to the DP’s newsroom, then located in the basement of Sergeant Hall, a 34th and Chestnut dorm that was demolished in the 1970s.

Throughout the day, the staff, working in the the grungy, dark newsroom that was filled with typewriters and yellow notepads, listened to radio reports and followed wire updates that they were receiving from the Associated Press.

“It was all sort of numbing,” said Ross, a 1964 College graduate, who is now a professor of political science at Bryn Mawr College. “You heard the news, but you couldn’t really digest it.”

The staff decided early on, said Ruthrauff, now an attorney in Philadelphia, that most of its coverage over the next few days would play out on the newspaper’s opinion pages. Staff members wrote columns, and the newspaper’s editorial board penned several editorials, doing what it could to bring the community together.

“We weren’t on the front lines of the hard, breaking news,” Ruthrauff said. “We had to understand what our place in all of this was.”

***

As soon as Kennedy was pronounced dead, Howard Marlowe knew that he needed to travel to Washington to see the president’s casket.

Several years earlier, it had been Kennedy who inspired Marlowe, a 1964 Wharton graduate, to take an active role in Penn’s student government. “I remember very clearly being inspired by him, because he stood for our generation more than anyone we’d seen before,” Marlowe said.

The Sunday after Kennedy’s assassination, Marlowe, now a lobbyist, piled into his gray 1958 Buick — “Mr. B,” he used to call the car — with five of his Penn friends. When they arrived in Washington in the late afternoon, they were met with a line of mourners that stretched for more than seven city blocks in front of the Capitol, where Kennedy’s casket was on display.

Marlowe stood in line all night long, waiting more than 12 hours to see the fallen president one last time. That night, the silence of the crowd’s shared grief was punctuated only by the sporadic sounds of transistor radios playing from various spots in the line.

Finally, at the break of dawn, he and his friends were allowed inside.

***

On the evening of Nov. 22, 1963, a senior tutor at the University of Oxford stood at the front of a large gothic dining hall and banged several times on his wine glass.

“We have just learned that the president of the United States has been shot,” he announced to the room.

Sitting in the hall for dinner that evening was Bruce Kuklick, who had graduated from Penn in the spring of 1963 and was now on a graduate fellowship at Oxford.

Kuklick learned about 30 minutes later that Kennedy had died. Later that night, some of his British classmates asked him if he wanted to talk about what had happened over a drink at the local pub. Kuklick said no. He just wanted to be left alone.

Kuklick, now a professor of history at Penn, spoke often in the wake of Kennedy’s assassination with a man named Frank, his British “scout” — a butler and housekeeper at Oxford. Frank, a stout, white-haired, red-faced man with a round head and a big smile, was Irish, and he had worshipped Kennedy since his election in 1960.

To his surprise, Kuklick found that, like Frank, many of his British classmates at Oxford were also deeply affected by Kennedy’s death.

“The people at Oxford recognized that Kennedy was the closest Americans were going to get to having royalty and aristocracy in office,” he said. “He represented a sort of democratic aristocracy that they could relate to.”

When Kuklick returned home for a holiday break in December, he was surprised to find a new addition in his living room: a framed photograph of Kennedy. Both of his parents had voted for Nixon in 1960 — his mother cried when Nixon lost the election — and neither had bought into the youth-infused fervor and optimism that had won Kennedy so much favor among college-age students.

“I was blown away by the fact that his death had converted these people into admirers,” he said. “Kennedy’s death had that ability to leave a lasting impression on them. It left a lasting impression on all of us.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.