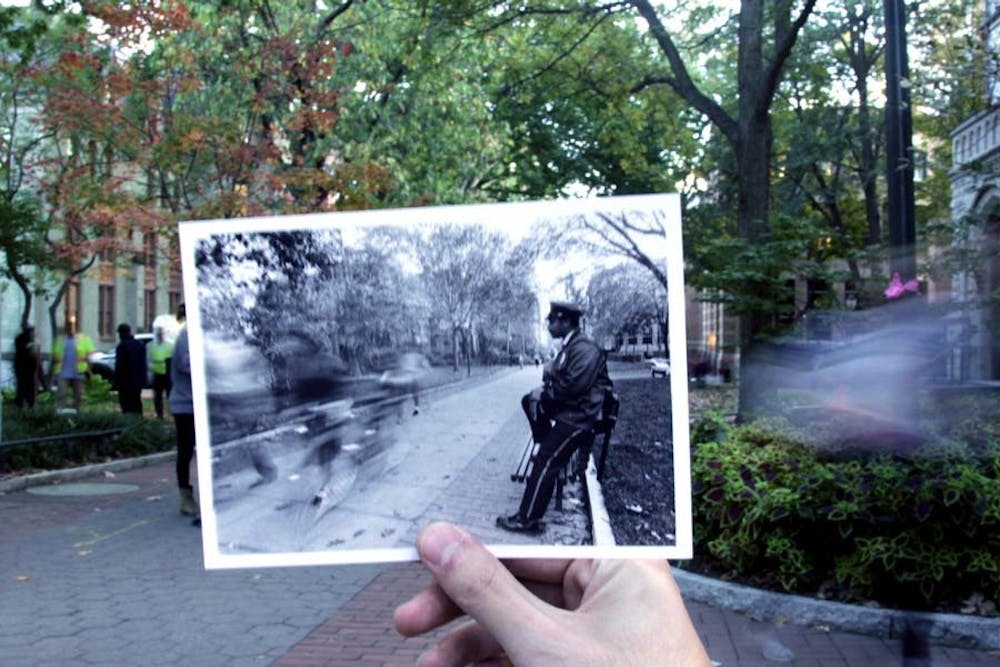

As recently as 40 years ago, the space now called College Green was covered in asphalt. Here, the DP visually compares past and present shots near Locust Walk and 36th St.

Credit: Tiffany PhamThough Penn laid its first buildings down in West Philadelphia some 140 years ago, a dedication to open green space has not always been an integral part of campus development.

Recently, high-profile projects, such as Penn Park and the Krishna P. Center for Nanotechnology Center, have expanded Penn’s green landscape all the way down to the Schuylkill River. University Landscape Architect Robert Lundgren described campus now as “a contiguous set of open spaces from 40th Street down to Penn Park.”

It was not always this way. Before the late 1970s, much of campus was essentially a parking lot. Asphalt covered the area between Van Pelt Library and College Hall, and Penn Park was also covered in asphalt and belonged to the United States Postal Service. “I’m not going to say ‘urban blight’ … but it’s a good word,” Lundgren said, describing the landscape of the past.

The first planning effort to emphasize the need for green space came in 1977, when the Center for Environmental Design in the School of Design created the Landscape Development Plan.

“Penn’s image at present is tarnished … a lack of initial planning has resulted in a vast agglomeration of buildings, without organic arrangement,” wrote Peter Shepheard, director of the Center, in the introduction to the plan.

Related: New program tests how green students are

The plan specifically pointed to lack of greenery as part of Penn’s problem. Trees on campus were “in ill health or in need of professional maintenance and care,” while flooding and erosion was “ubiquitous.”

Shepheard’s plan was to transform the campus by planting greenery “designed to mature into a stable landscape” and creating a “functional and beautiful path system, with paths where people want to walk.”

In the years after the Landscape Development Plan, all of College Green was turned into the lawn area it is today, with cobblestone and brick replacing the paved roads.

“It’s in our DNA of campus planning,” said Mark Kocent, principal planner for Facilities and Real Estate Services. “The landscape is what holds the campus together.”

Even now, Penn is still removing asphalt where it can to make way for green space. The University added 157,000 square feet of open space in fiscal year 2012-2013. “The Nanotechnology Building that just opened, that was a parking lot,” Kocent said as an example of their work.

In the case of Penn Park, Kocent says that strong demand for field space and inadequate facilities for athletics motivated the idea to make all of the fields recreational, or what he calls an “active landscape.” This decision made Penn Park a more sustainable location, as landscapers filled the area with turf, which requires far less energy to upkeep than grass.

Even more than the quality of open space, Lundgren emphasizes that people need to connect to it, calling the spaces “a really central piece of learning.”

Another recent example of Penn’s continuing work is Edward W. Kane Park, located at 33rd and Spruce streets, which used to be a parking lot used mainly for the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

Renovation of 40th St. trolley station: Concrete to green

“One of the things the hospital didn’t have was open space, and they said they’d love to have it,” Kocent said. The park’s renovation began in 2012 and finished this fall, and now contains an half acre of green area.

These larger open spaces also help with sustainability and infrastructure on campus. In 2006, the city passed a regulation requiring private landholders to capture a certain amount of rainwater — a measure that saves sewage from entering the river, keeps the river from flooding and alleviates some of the burden on Philadelphia’s aging pipes. When they built Shoemaker Green and Penn Park, landscapers were able to construct large collection tanks underground, which handle rainwater collection for much of that area of campus. The system then uses the captured rainwater to irrigate the fields the rain falls on.

“From what I’ve seen over the past 20 years, Penn has been doing a good job of creating open spaces,” Richard Berman, a lecturer in the Urban Studies department, said in an email. ”In general, one way open space can be beneficial, is by handling runoff of water. If the space was originally a parking lot with a traditional paved, impervious surface, then stormwater would run straight to a sewer drain. Because of Philly’s combined sewer system, this can be a problem during a heavy rain, since it can overwhelm the city’s filtration systems, as it runs into the river.”

Related: Penn steam facilities turn green

However, even as the University praises the benefits of open space, it is looking to build a large new college house on Hill Field which could remove a large part of the field. The college house is set to start construction in January 2014.

However, Lundgren said, “[Hill Field] will be even more usable. The building will define the space better.” What’s important, Lundgren says, is the quality of the space.

“Just because we’re urban doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have a relationship with the outdoors,” he said.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.