They almost blend into the background - posters as worn and dirt-splattered as the grafittied walls that wear them.

Yet the messages proclaimed by two versions of anti-Penn posters currently plastered across West Philadelphia are anything but passive or forgotten.

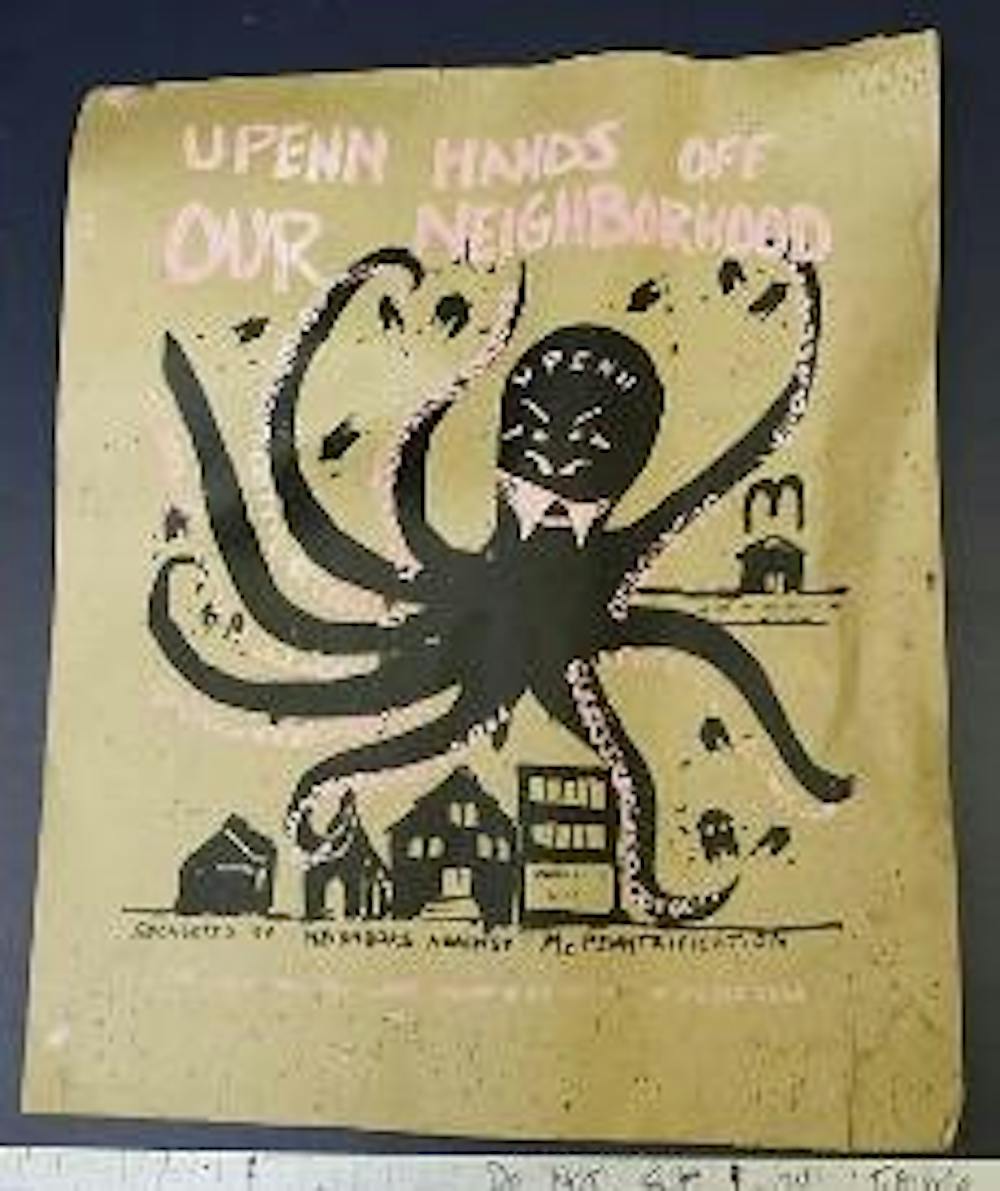

One version is general, graphically depicting Penn as a tentacled monster and urging it to keep its hands off West Philadelphia.

In large block lettering, the second version recalls Black Bottom - an area that Penn developed during the 1950s and 1960s, displacing a number of local residents - and cautions against West Philly being "next."

Since they appeared on the streets last fall, the posters have been torn down, grafittied themselves and labeled vague and ungrounded by critics both within and outside the University.

But for the artists - two West Philadelphia residents - and those with objections to Penn's influence in the region, these posters serve both as markers of solidarity and reminders of a fight against the University that, despite having lost some momentum, is far from finished.

Signs From the Past

Though they are a recent addition to the West Philadelphia scenery, these posters are conceptually derived from a print developed and distributed by one of the artists years ago.

According to Rev. Larry Falcon - a West Philadelphia resident for over 30 years - original versions of the poster emerged in about 2001; around this time, some West Philadelphia residents were forming a resistance to a Penn proposal that would move the McDonald's at 40th and Walnut streets to 43rd and Market streets.

Eventually, the proposal was withdrawn due to local opposition and the discovery of chemical contaminants at the Market Street site, but remnants of the cause lived on through the unification of anti-Penn activists in a group entitled "Neighbors against McPenntrification," led by Falcon, and through a batch of posters distributed by the group to local businesses.

The posters, Falcon said, were crafted by a member of NAM who originally printed about 50 copies on brown butcher paper.

Unlike the current posters, the sheets distributed six years ago featured a portrayal of Penn as an octopus hovering over 40th Street. With menacing eyebrows and pink fangs, the symbol bore a similar message to the one the current posters promote: Stop UPenn, hands off our neighborhood.

Falcon said that, though the posters were not commissioned by NAM and were entirely the artist's initiative, they soon caught on among businesses and community members who shared these sentiments.

"We put them up in the windows, especially along 40th Street," Falcon said of the posters, which included his contact information. "People came by and wanted to buy" them.

And Roger Richards, a member of both NAM and Friends of 40th Street - a Penn-led group that works to bring retail to the 40th Street corridor - said that the same artistic elements and anonymity which attracted people to the original print hold true for the posters currently circulating.

"We can all make educated guesses [about the posters], but I don't many people who know very much about it."

And the artists intend for it to stay that way.

Building a Movement

Updating and redisseminating the anti-McPenntrification print is a task that the original artist, who asked to remain anonymous due to the illegality of the postings, had long planned to complete.

Not intended to antagonize, the revamped posters "come from a place of frustration," the artist said, and "worrying about what is happening to your neighborhoods and your friends who live across the street from you."

She said that, in particular, she and her partner aim to express opposition to the method of development in West Philadelphia, not the existence of it.

Specifically, she said, higher rent prices force individuals to leave their homes, and local businesses get forced out by national chains that are willing to pay higher prices for retail space, particularly along areas like the 40th Street corridor.

"Cities need this, but what I see happening and what a lot of people are concerned about is how that development and redevelopment ends up excluding the very people who have been here the whole time," she said.

Accordingly, the artist said that one of the most rewarding aspects of creating the posters has been talking with people in the community while posting them.

"I remember this one girl's face being like, 'There are people out here doing this thing that we believe in' - that's one of the things that I love about it."

So much so that, in addition to the 200 prints currently posted, she and a friend are planning a new batch, created through silk screening.

"I am an artist, for sure, but it is hard for me to not make work that addresses or deals with a lot of the things that I am concerned about. . They ended up being part of the same story."

Gauging a Reaction

But because the posters are primarily plastered across telephone poles and abandoned buildings north of Market Street and south of Baltimore Avenue, there is a chance that the story will fail to reach the characters it implicates.

Even some Penn officials directly involved in partnering with West Philadelphia were not aware of the posters prior to being interviewed for this article.

Glenn Bryan, Penn's assistant vice president for community relations, said that, while signage is not the most popular form of protest against Penn, the ideas presented are not unfamiliar.

"We don't see this that often, but there are community groups that have not-positive sentiments toward the University's practices," Bryan said.

And as for Penn's reaction to claims that they should stop interfering in the area?

"We are part of West Philadelphia, and that's the response," Bryan said.

Tony Sorrentino, the University's spokesman for facilities and real estate, said that the University currently does not have any development projects west of 40th Street, and that its relation to West Philadelphia is not grounded in real-estate ventures, but rather in community partnerships.

Additionally, Sorrentino acknowledged that the development focus for the University in the coming years will likely be on the postal lands - a 42-acre plot adjacent to Penn's eastern edge.

Regardless of this turn to the Schuylkill, the University's general influence is what is causing activists to stand behind the posters for the second time.

"I think that community activists are greatly encouraged that there is still someone out there fighting," Rogers said.

David Onion, a West Philadelphia resident and member of the Defenestrator, a local anarchist newspaper, agreed that the artists' gestures are still relevant.

"Most people I know are pretty sympathetic to the posters," Onion said.

He added that the support for the current signage stems from local individuals - such as the artists themselves - who object to the area's rising cost of living, which he said is attributable to Penn.

Currently, Penn is not directly acquiring properties west of 40th Street. However, it is a financial supporter of the University City District, a local non-profit group dedicated to preserving the safety, businesses and attractions of the University City area.

The rise in housing costs in the area has been attributed to UCD's efforts to make the area more upscale.

"If doing the work of University City District can make University City cleaner and safer, and as a result prices are being driven up, that is out of our control," said Lori Klein Brennan, a spokeswoman for UCD.

Brennan added that, while she has not seen the posters herself, it is illegal for groups to hang posters in the area without official licensing.

Still, the audacity of the work contributes to its effect, Rogers said.

"I think it has raised an eyebrow," he said. "I think it has reawakened an interest against the campaign against uncontrolled development."