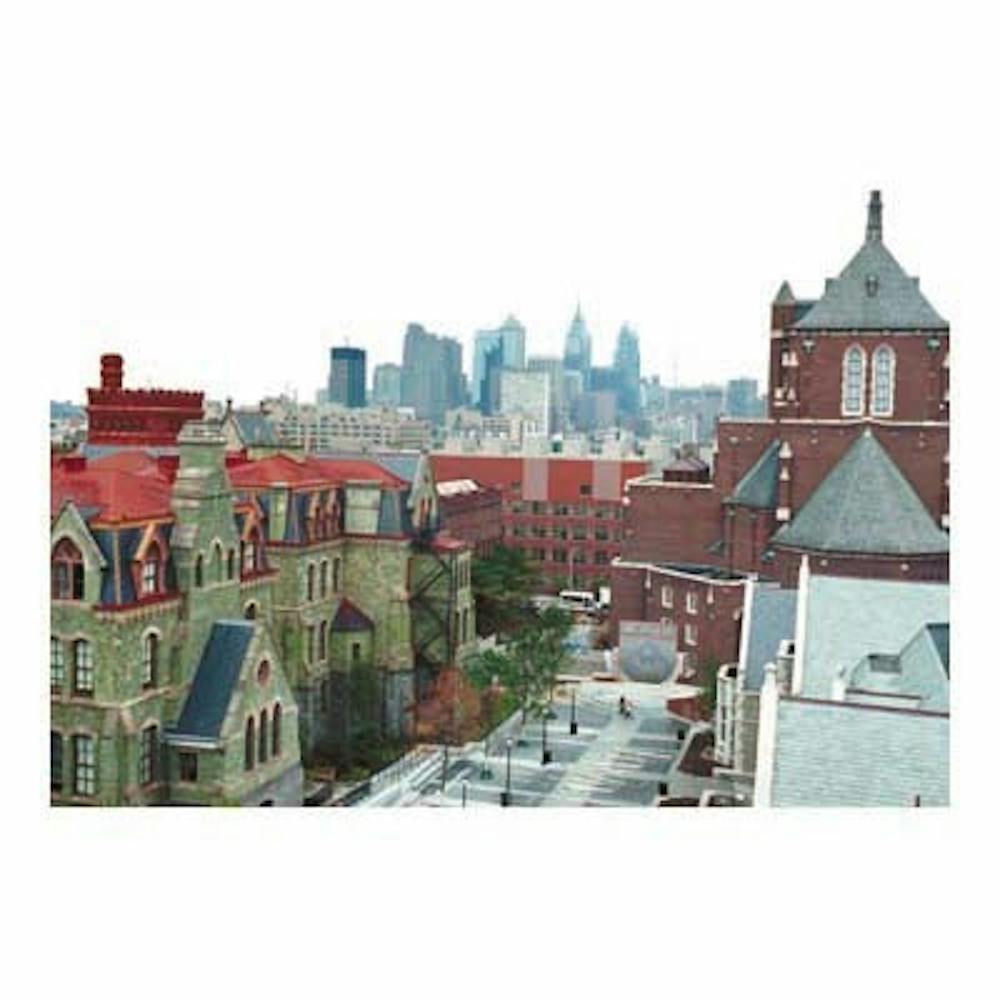

It's no surprise that Penn officials have been anxiously awaiting the grand opening of Perelman Quad this fall. The $87.5 million project will restore the University's most historic buildings, linking Irvine Auditorium with College, Logan, Houston and Williams halls to create a center of student life on campus. What is surprising, though, is how long they've been waiting. Try 15 years. Even University President Judith Rodin concedes that her pet project has gone anything but smoothly. Since University Trustee and Revlon CEO Ronald Perelman signed on as the project's lead donor, the student life initiative has spanned two architectural firms, three University presidents, four provosts, multiple designs and redesigns and enough planning committees, financial setbacks and administrative delays to rival a Congressional filibuster. "The road to Perelman Quad has been windy at best," Rodin said in May. And at worst? "Rocky." The original conception for the Perelman Quadrangle dates to 1985, when a group of students who were dissatisfied with the services and spaces in Houston Hall -- the nation's oldest student union -- approached administrators with their concerns. After meeting with campus officials and other student leaders, those students eventually saw their idea incorporated into the Undergraduate Assembly's 1985 campus master plan, which outlined its vision for what Penn should look like by 1990. The idea gained steam as it made its way up the ranks of College Hall. But it would have to pass through four years of delays before it gained the Trustees' approval. A planning committee had to be charged, an architectural firm had to be hired, feasibility studies and architectural blueprints drawn up. And most challenging of all, funding had to be in place. "It takes a long time for a big project like this to work its way up," then-president Sheldon Hackney, now a History professor, explained. "A lot of it was finances." While the University's development office sought out a donor, in 1989, Hackney and then-Provost Michael Aiken charged a committee of students, faculty and staff to identify what Penn students wanted in a new facility. But with a laundry-list of University constituencies, that charge sounded a lot simpler than it was. Based on site visits to 12 universities, the committee drew up an ambitious wish list. It included additional space for student organizations and performing arts groups, a black-box theater and auditorium, a 24-hour study lounge, an art gallery, a game room and a food court. Despite the reservations of some administrators and Trustees, Penn hired an architectural firm and went ahead with the plans. The project was budgeted at roughly $60 million. A location for the new student center was identified at 36th and Walnut streets -- the current site of Sansom Common. But despite the blueprints, there still was no money on the table until 1990. That's when Hackney secured a $10 million gift from University Trustee Ronald Perelman, a 1965 Wharton graduate and MBA recipient. The new student union would be named the Revlon Center for the cosmetics company Perelman headed. But other donations were slow to trickle in. Besides Perelman's gift, just $1.5 million in additional funds were pledged for a project budgeted at about $65 million. Prospective donors were frustrated with the lack of progress and uncertain about the future of a project that had been slated for completion in 1994. Those fears only escalated with the interim leadership of Claire Fagin and Marvin Lazerson, who became president and provost when Hackney and Aiken resigned. Not wanting to nix the project altogether, the interim administration said they would not present the plan to the Trustees until additional funding was guaranteed. Meanwhile, the Trustees determined that the University could not afford such an expensive project. And in the fall of 1993, Fagin and Lazerson slashed the project's budget, dramatically reducing the student center's scale and scope. Once again, construction was delayed -- this time until 1995. Rodin's appointment as Penn's new president only slowed the process. In 1994, she brought the redesigned Revlon Center's plans to a halt. "It was very clear that many of the Trustees were dissatisfied with the size, with the design and with the fact that students would have to cross Walnut Street," Rodin said. After further review, Rodin commissioned a new architectural firm to make recommendations for a facility. Their findings, she said, underlie the current plans for Perelman Quadrangle: restore and connect the University's old, historic buildings to create a center of campus life. "They argued very forcefully that you put the student-centered activities where the student traffic patterns are," Rodin said. That meant when Rodin and then-Provost Stanley Chodorow announced their plans for a $69 million Perelman Quad in 1995, it would include most of the facilities originally slated for the Revlon Center. But it would be in a new location. The project called for the complete restoration of College Hall, and Logan Hall would be renovated to create an art gallery, multi-purpose auditorium and recital hall. Logan Hall would be connected to Williams Hall in two ways -- through an underground tunnel and through a two-story glass atrium containing a 24-hour study lounge. And Irvine Auditorium would receive a facelift and renovations. The centerpiece of the project, though, would be the remodeling of Houston Hall. The architects envisioned it becoming home to more than 250 student and performing arts organizations, study and lounge space, a music-listening center, card and copy shops, a video arcade and game room as well as a food court with a range of dining options. However there was still no commitment from the project's primary donor. That changed when Rodin met with Perelman, lobbying him for support of the new location. It worked: Not only did he remain committed to the project, he doubled his initial gift to $20 million. With Perelman's contribution solidified and construction plans in place, alumni responded to the project in growing numbers. More than $5 million was raised through alumni small class gifts. And others stepped forth with larger ones. University Trustee Stephen Wynn, a 1963 College graduate and casino mogul, donated $7.5 million for an open-air Wynn Common space. And University Trustee David Silfen, a 1966 College graduate and Goldman Sachs investment banker, donated $2 million for a 24-hour study lounge in Williams Hall. The University kicked in its own capital project funds, and a fundraising goal of $38 million was set, which was met two years ago. Construction on the project finally began in 1996, with University officials predicting completion by the end of 1999. But the plans, as always, were just a little too optimistic. Delays ranging from the removal of the old swimming pool in Houston Hall to the destruction of air conditioning units by Hurricane Floyd last fall pushed the grand opening back until this July. Still, while Rodin and others celebrate the grand opening this fall, they should be glowing with as much pure exuberance as utter relief. Indeed, when administrators spoke of Perelman Quad they said, "We had this gem, so why not polish it to make it serve student needs?

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.