Last fall, a plethora of new results from U.S. News & World Report, Wall Street Journal, and Forbes elevated Penn in their national college rankings. Nearly every list places Penn among the top 10, some going as far as placing the University among the top five. This universal growth resulted from a key change in most of these sources’ metrics: greater consideration given to postgraduate salaries.

Penn famously has one of the highest-earning alumni bodies in the country. Starting salaries for Penn graduates are often considered the highest in the Ivy League. By mid-career, the average Penn alum is raking in $165,000 annually, while the national average for a college graduate caps out at $74,000.

Penn draws a great deal of prestige from its potential to produce high earners, which is a direct result of our school’s preprofessional culture. Nearly 50% of all Penn graduates enter one of two career fields: consulting or finance. This pipeline allows most Penn alumni to matriculate into high-paying jobs shortly after graduation.

I’m usually a defender of preprofessionalism. It’s crucial that Penn graduates are able to find good jobs, and high salary potential is an immense advantage. But those jobs aren’t everything. Many universities are making gains in rankings and name recognition based on alumni outcomes in public service careers.

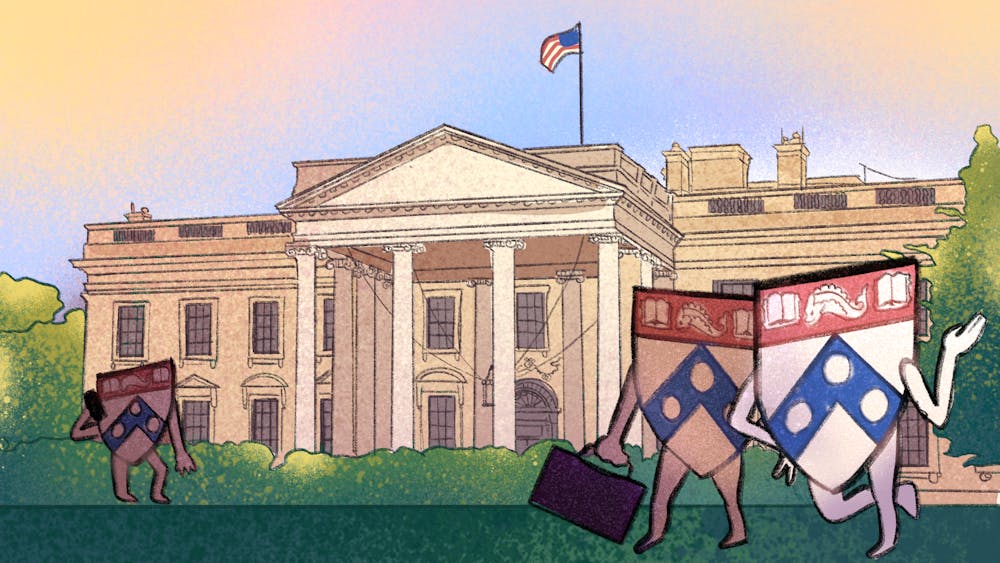

For example, Harvard University boasts about its eight presidential alumni. However, when 1968 Wharton graduate Donald Trump was elected president, Penn mostly ignored his history with the school. Given his proximity to controversy and his unconventional political history, Penn’s bump in prestige was limited by Trump’s election. Our second closest claim to the White House is the University’s relationship with President Joe Biden and the opening of the Penn Biden Center. I argue that this is as far as Penn’s ties to the presidency will go. Nowadays, Penn’s laser focus on professional development might repel students who will one day have presidential potential.

Comparable institutions to Penn have high-earning graduates and prestigious placements throughout the government, nonprofit sector, and the advocacy space. For example, Georgetown University feeds graduates into congressional offices and many Fulbright programs. Princeton University also regularly features its flashy roster of graduates in powerful political offices. These universities maintain a strong presence in the private sector but are also actively represented in government positions.

In these examples, the institution itself sponsors an undergraduate school dedicated to public service. At Georgetown, it’s the School of Foreign Service, while at Princeton the role is filled by the School of Public and International Affairs.

I propose that Penn follow suit and create a fifth undergraduate school dedicated to public affairs. This new school could absorb Penn’s wildly popular social science programs, like PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics), Political Science, and Economics. Currently, most students in these majors are scooped up by consulting firms and investment banks. If these students were given an intentional focus on service and social responsibility, perhaps they could feel empowered to use their degrees in a more meaningful way.

The least Penn can do is expand its current effort to bridge the gap between social science degree seekers and careers in government and nonprofits. It’s crucial that our student body actively engages with the robust policy infrastructure that Penn has already made available: Civic House, Perry World House, opportunities like Penn in Washington, and extracurricular engagements offered by the Government and Politics Association. From what I’ve seen, these resources are underutilized at Penn. By snubbing them, Penn students are working against the general interests of the University to gain prestige.

Besides, it's about more than just rankings. We have the potential to empower our students to become leaders in society. TIME Magazine ranks Penn as the third-best college for aspiring leaders. However, the article states its rationale for this placement as a concentration of graduates in business careers. Other chart-topping schools on this list were noted for their programs in law, medicine, and more.

Ultimately, private sector homogeneity marks one of Penn’s key weaknesses. As we move forward, Penn has a duty to educate leaders in more than one field. If Penn strengthened its programs in civic engagement, more graduates would be inclined to pursue roles in government and could elevate Penn’s cultural stature. We should be known for more than salaries. We can do more than business.

JACK LAKIS is a College first year studying political science from Kennesaw, Ga. His email is jlakis@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate