The next time you play Angry Birds, World of Warcraft, or Tetris, you might be making yourself a better person and the world a better place.

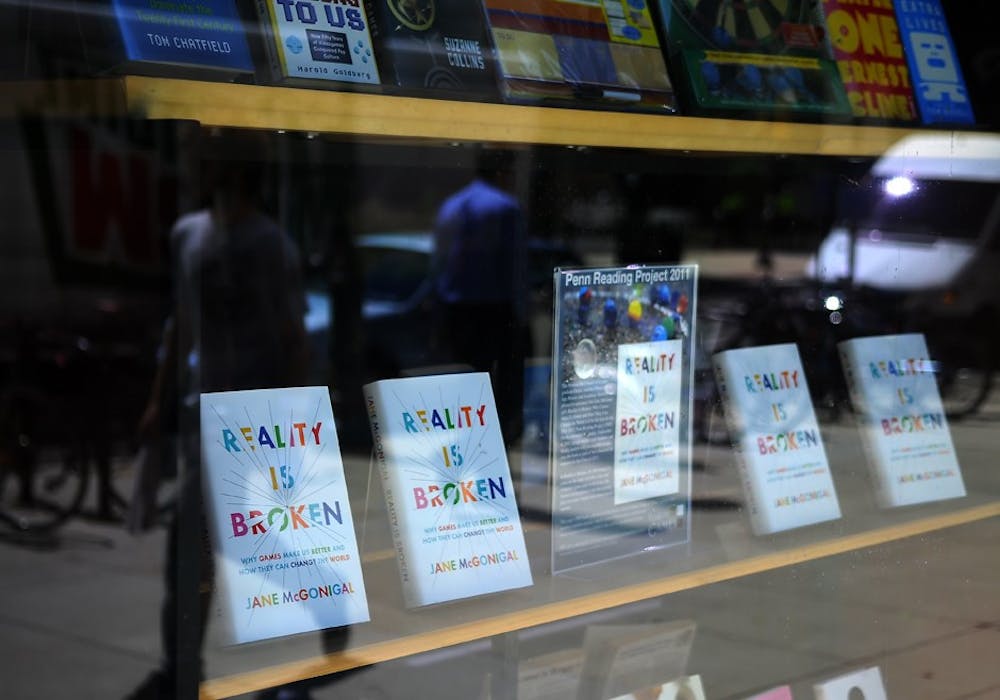

This is the message that Jane McGonigal preaches in Reality is Broken, the book selected for the Class of 2015’s Penn Reading Project.

McGonigal, a game designer, claims that reality is depressing, unproductive and hopeless. But she thinks that playing more games and utilizing gaming culture can improve real life.

Reality is Broken explains how games trigger adrenaline rushes that ultimately make us happier and more productive. By consistently challenging us to work at the frontier of our endurance, engaging games trigger “fiero,” an emotional high.

Scientists say that fiero is one of the most powerful adrenaline rushes we can experience. It fires signals in the part of the brain most typically associated with reward and addiction.

Using gamers’ wits, McGonigal wants to transform real life tasks into games.

McGonigal uses the example of Quest to Learn, a public charter school in New York, where math assignments are called “secret missions,” earning a good grade is “leveling up” and enrichment activities are “Boss levels.”

While Penn freshmen are unlikely to find classes that incorporate games, Marketing 101, “Introduction to Marketing,” regularly includes a market simulation game, where teams of students compete as firms in a virtual market to earn the most amount of revenue by employing effective marketing strategies.

My own experience with the class confirms McGonigal’s argument. I learned more from the game than from the lectures, because the game provided an interactive, competitive and hands-on approach.

Games may not just be for elementary schools, but could play a large role in a research university. At Penn, we could do with more of these games in the classroom, where the traditional lecture and slides model is proving to be redundant and unengaging.

McGonigal also has larger goals in mind. She believes we can use games to prepare ourselves for the future and sustain the planet — to create “epic wins” in reality.

Gamers constantly work toward self-improvement (getting a higher score), use teamwork effectively, set realistic goals and play by the rules. These attributes constitute a recipe for success in the real world.

By tapping into the gamers within us, McGonigal says we can better collaborate with each other to find solutions to challenges we face.

For instance, World Without Oil — an online reality game created by McGonigal — simulates a global oil shortage. The game challenges teams of experts and laypeople to come up with creative ways to live without oil. This results in a diverse range of solutions to a problem we may face in the future.

However, this idealization seems far-fetched. It is doubtful that everyone would be willing to participate in “a whole planetary mission … to raise global quality of life … and to sustain our earth for the next millennium and beyond.”

Frankly, at a place like Penn, engaging in a universal mission about sustaining the earth is not high on our list of priorities, and it would take a great deal of effort to round up such a movement.

But games do have the potential to make studying for a midterm, cleaning our rooms and exercising at Pottruck less tedious.

As a whole, McGonigal’s argument is worth considering. It is a fresh perspective on making the world a better place. Convincing and comprehensive, McGonigal presents many relevant, albeit small-scale examples of existing games that have made a positive impact.

However, we have to stop and consider that McGonigal’s prescription may not be a permanent fix. Even if games did solve some of society’s problems, there is no guarantee the solutions will last. McGonigal also does not consider possible problems that could arise with widespread gamification.

And honestly, is reality really that bad?