There were only two weeks left in the 2012 Penn softball season when then-sophomore Mikenzie Voves decided to quit the team.

Before she quit, Voves had been one of Penn’s strongest pitchers, winning 21 games and throwing 156 strikeouts for the Quakers. Despite that, Voves felt like she wasn’t wanted on the team.

Voves announced her resignation to the team in an email that was forwarded to The Daily Pennsylvanian by Jim Metcalf, who is the parent of former Penn softball assistant coach Devon Metcalf and former Penn softball player Hayley Metcalf. In the email, Voves also included the message she shared with Penn softball coach Leslie King, who has coached at Penn since 2004.

“Coach King, I am not unique on the team with regards to many of the feelings that have festered and grown inside of me for the last two years,” Voves wrote. “Girls are frightened of talking to you, many are depressed on some level, some have their parents come on a regular basis to keep them together and others feel lost and forgotten.”

Then-sophomore Mikenzie Voves quit Penn softball in 2012 with only two weeks left in the season. // File Photo

Voves’ departure came just two years after the DP reported that four Penn softball players quit the team before the 2010 season. At the time, King was adamant that the players’ decisions to quit were not part of a larger trend within the program.

“If you’re looking to see if there is some kind of underlying problem in our program, you’re barking up the wrong tree,” King told the DP in 2010. “It was just an isolated thing that some years it happens.”

Eight years later, evidence suggests that King’s alleged insensitivity to the physical and mental well-being of her players was not an isolated problem, though not all the players feel this way. Penn Athletics declined to provide official data on the team’s retention rates, but the DP has found evidence to suggest that since 2010, 26 players have left the team before their senior seasons. While online rosters of the team are missing dozens of names, the DP reached this number after combing through archived stat sheets from each year.

By comparison, according to an online list of Princeton softball’s letterwinners organized by year, only five players left Princeton softball over that same time period. And since former Penn assistant coach Lisa (Sweeney) Van Ackeren was hired as the Tigers’ head coach in the summer of 2012, every incoming player in the graduating classes of 2016 through 2018 has stayed on the team for all four years.

A representative from Princeton Athletics confirmed these numbers, but the DP did note five discrepancies between the list of letterwinners and Princeton’s archived stat sheets. After the DP requested an explanation for the discrepancies, Princeton Athletics responded that the discrepancies were “corrected where applicable,” but that the retention numbers still remained the same.

The Ivy League did not respond to multiple requests for league-wide data.

In all, five former players, one former assistant coach, and three parents of former players shared complaints about King’s coaching with the DP. Three of the former players asked to remain anonymous, while the other six sources spoke on the record.

Some of the sources’ complaints were related to disagreements with King’s approach to practice and game management, but other allegations were more serious. These allegations raise questions about whether the pressure King imposed on her players crossed the line into mistreatment.

King declined to be interviewed for this story. In response to multiple requests for comment in January, Penn Athletics referred the DP back to a written statement provided by King in December of 2017.

“Students do leave the program,” King said in the statement. “Every student has their own unique experience and their unique reasons for leaving. Each time it happens, we take it to heart and reflect upon why they leave and what we can learn from it as coaches.”

In a statement provided to the DP on Jan. 30, Penn Athletics discussed the relationship between coaches and athletes but did not address the specific accounts described by the athletes on the softball team.

“When our student-athletes arrive on campus as freshmen, it is certainly our hope that all of them will leave four years later having had a positive intercollegiate experience,” the statement read. “The coaches and staff members involved with Penn Athletics take pride in the efforts they make to enhance the quality of the student-athlete experience, and that process is ever-evolving as issues such as mental health continue to emerge.”

• • •

“That’s how it is in sports”

Leslie King is entering her fifteenth year as Penn softball's head coach.

Prior to coaching at Penn, King briefly coached at Lock Haven University and later George Washington University. Before those stints, she enjoyed a long and successful playing career in both softball and soccer.

During her fourteen years as Penn’s head coach, King has enjoyed a winning record. Under King, Penn won the South Division title four years in a row from 2012 to 2015. In 2013, the Quakers made an appearance in the NCAA Tournament after defeating Dartmouth for the Ivy League title.

King has also seen her players win Ivy League Player of the Year three times, including outfielder Leah Allen, who earned the honor last year in her senior season. According to Allen, King helped her reach her full potential.

“There were times when the coaches were tough on you, but that’s expected in any sport,” Allen said. “That’s how it is in sports, sometimes you need to ride people to get them to do well, so it wasn’t anything unexpected.”

Katarina Pance, a current senior who quit the team in January 2015 due to an injury, also praised King.

“I think Coach King was supportive while I was battling my injury,” Pance told the DP in an email. “I think she was disappointed when I informed her that I would be leaving the team, but since then I've run into her a couple times and she's been supportive in those encounters.”

Penn Athletics declined multiple requests to make any current Penn softball players available for comment, but according to senior and former Penn softball outfielder Sarah Rowley, dissatisfaction with King is prevalent even among players who have stayed on the team.

“One girl who’s on the team currently told me that I was smart to quit,” Rowley said.

Former assistant coach Devon Metcalf also sensed frustrations with King from players during her only year at Penn in 2013. While Metcalf reported that she got along personally with King, she felt that most of the team’s success that season could be attributed to the leadership of the team’s seniors, not King’s coaching.

“I think [King has] almost outgrown the program, because she’s been there so long. I don’t know if she’s giving herself fully to it anymore,” Metcalf said. “They [the seniors] just had to keep everything set with the team and hope that they weren’t going to be coached out of games I guess.”

The anonymous former player who played all four years on the team said she thought that King gave better treatment to her favorite players.

“If you kissed her ass, that’s the way in,” the player said.

But that player also thought that even King’s favorite players didn’t like her.

“Everyone hates her. They’re completely doing it for their own benefit,” the player said.

• • •

“If you’re hurt, you’re hurt”

It didn’t take long for Rowley to realize that Penn softball wasn’t exactly what she thought it would be.

“I remember like halfway through my freshman fall feeling like I didn’t really belong on the team,” Rowley recalled about her first year at Penn in 2015.

Rowley soon became closer with her teammates, but her relationship with King never improved. She described several incidents where she felt King had especially crossed the line.

One of those incidents was in January 2016. Rowley was participating in her first practice since undergoing major knee surgery for an earlier injury. After nearly an hour of intense conditioning workouts, Rowley stopped before the rest of her teammates finished. It was her first day back and she did not want to risk further injury by pushing her body too hard too quickly, she said. According to Rowley, an assistant coach also agreed that she should have stopped, but King scolded Rowley for doing so.

“Coach King yelled at me in front of everyone,” Rowley said. “I was so happy to be back, and then she yelled at me. And so I went home — practice ended at 11 — I think I cried until I had class at 4:00. I was miserable.”

“It was awful,” Rowley’s mother, Toni Richards-Rowley, said. “That was what ultimately decided it for her.”

Richards-Rowley added that she thought King “absolutely” placed pressure on her daughter to return prematurely from injury, putting her at risk for further harm.

“There was no kind of understanding of the potential badness that could have happened.”

Rowley was not the only former player who felt that King pressured players to return quickly from injuries.

Right before the 2014 season, one former player, who did not respond to requests for an interview, wrote an email to the team announcing her decision to quit. In the email, which was also forwarded to the DP by Jim Metcalf, the former player explained that her decision to quit was based largely on her frustrations with King.

Just a month before sending the email, the player had undergone surgery. According to the email, more than half of the players’ teammates “wished me good luck or checked in to see how my surgery went,” but none of the three coaches ever contacted her. This was not the first time the player had felt neglected by King after an injury.

“Every injury I have endured, Coach [King] has ignored or mocked me for,” the player wrote. “After she didn’t ask about my surgery, I realized her respecting me as a player and person was hopeless.”

Another former player also recalled feeling implicit pressure from King to rush back from injuries. She said that when she had to rest during training while recovering from injuries, King would occasionally ask why she was resting

Voves, the player who quit at the end of the 2012 season, also recounted frustrations with the way King and the other coaches handled her injuries.

“It was made very clear that advice from athletic trainers and doctors that was passed along was basically ignored by the coaching staff,” Voves said.

“I know they’re doing their job, I know you can’t single out players and treat them differently, but if you’re hurt, you’re hurt.”

• • •

“Rough to even make it through”

Just days after the incident on her first day back at practice after knee surgery, Rowley officially resigned from the team. She ultimately cited family reasons for quitting, but Rowley said that another key reason was the impact that King had on her mental health.

“It was definitely easy to see that the thing that was affecting my mental health so drastically before the stuff with my family happened was softball,” Rowley said. “And after [King] had me do all these exercises, it was clear that I really needed to get rid of that aspect of my life in order to move on and be happy."

“I was just thinking if nothing’s ever going to change, is it a good idea to keep doing this for the rest of my college career if I’m so miserable?”

Other players also thought that their experiences on Penn softball intensified their challenges with mental health and were disappointed with the way King handled their struggles. In addition to Rowley, two other former players, who both asked to remain anonymous, sought counseling at CAPS during their careers with Penn softball.

While traveling with the team for a tournament in 2009, one of those former players said that she committed self-harm. After the player returned to Penn and it was discovered that she had harmed herself, the player learned that she would be disciplined.

“I came back and I was suspended for two weeks with no real explanation as to why. It was sort of like ‘go get some help’ — it was framed that way and it was a decision that was above coach King’s head,” she told the DP in a recent interview.

While the player struggled to reunify with the team after the suspension, she said she does not blame King or Penn softball for the challenges she faced while on the team.

“I don't attribute my mental health challenges as caused by Penn softball, but they were exacerbated by the pressure to achieve and the culture of trying to stay tough no matter what. I think that can happen to any athlete in any sport,” the player said via email.

That player quit the team before the start of the 2010 season.

Voves also shared that her mental health suffered while playing on the team. After failing to form a positive relationship with King during her freshman year in 2011, Voves hoped that she would grow more comfortable on the team as she gained more experience. Instead, things got worse to the point that she left the team before the end of the next season.

“Sophomore year was definitely … it was rough,” Voves reflected. “It was rough to even make it through that one.”

After quitting the team in April, Voves only spent a couple more weeks on Penn’s campus. The next fall, instead of returning to Penn for the start of her junior year, Voves enrolled as a transfer student at the University of Washington. She did not play on the Huskies’ softball team.

Years after leaving Penn, Voves is still struggling to understand how her experience with the team could be so negative.

“I was struggling on a personal level and went to my coaching staff and told them, 'This is what’s going on,' and I’ve reached [out] for help with them and with the University, and you know, I got no support. Not once in two months did my coaching staff even ask me if I was doing any better, if I was doing okay,” Voves said.

“That’s what I guess I don’t understand. You know you’ve got a kid coming to you saying please help and you see her everyday.”

Voves then paused before continuing.

“And you don’t help.”

• • •

“How does that not raise a huge red flag”

All of the players interviewed for this story reported that no one from Penn Athletics ever initiated contact with them after they left the team, but at least one former player made an effort to voice her concerns more directly to King when quitting the team.

That one player, who asked to remain anonymous, said she met with King on the first day of classes in the fall of 2016. The player brought a “cheat sheet” with a list of issues she wanted to discuss with King, and according to the player, King was initially receptive to the player’s complaints. That changed when King realized the player had no intentions of staying on the team.

“Immediately when she found out I was quitting, it was like something shut off in her and she just didn’t want to hear me talk anymore,” the player recounted. “I think [King] said, ‘What you said doesn’t matter anymore now that you’re quitting.”’

When Rowley made her decision to quit the team in early 2016, she considered requesting a meeting with King to share her reasons in person. But the team’s first competitions were only days away, so Rowley opted to just notify King by email instead.

Rowley had met with King a few months earlier in the fall of 2015, and according to Rowley, the meeting was “unproductive.” Rowley said she also thought of the experiences of other former teammates who had left the team before her.

In the weeks after Rowley left the team, her parents said they sent an email to Penn Athletics in an effort to file complaints and prevent the renewal of King’s contract. Rowley’s parents also responded to a general anonymous survey about Penn Athletics titled “Enhancing Life Skills, Leadership, & Character Development in PENN Athletics.” The DP has not been able to confirm whether or not King’s contract was up for renewal at that time.

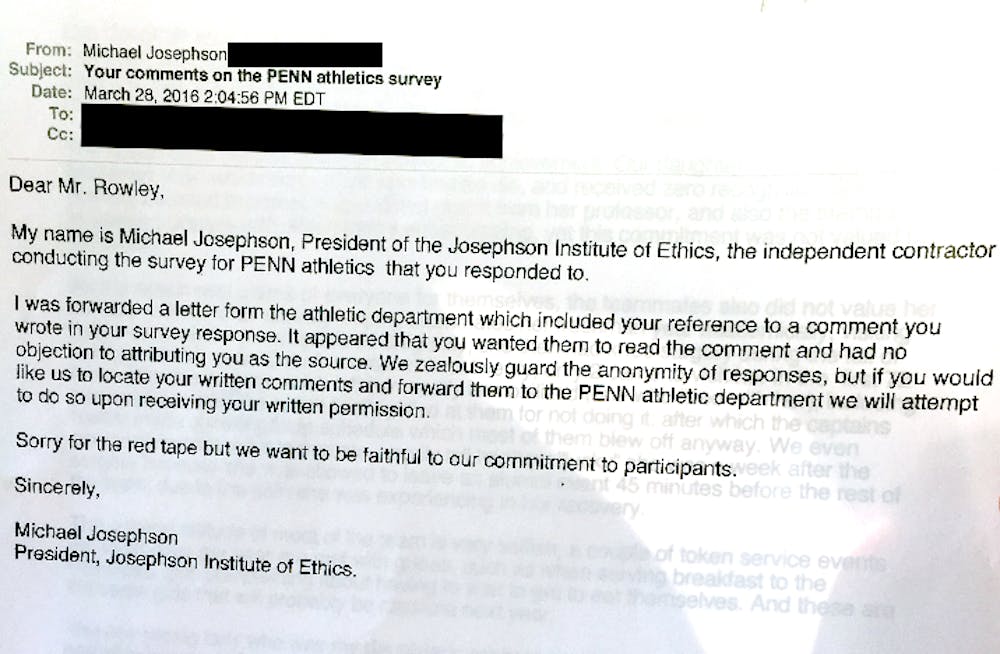

Neither of Rowley’s parents reported receiving any responses from Penn Athletics administrators. In March 2016, however, Rowley’s father received an email from the Josephson Institute of Ethics, which was the independent contractor that conducted the anonymous survey for Penn Athletics that he responded to.

“I was forwarded a letter from the athletic department which included your reference to a comment you made in your survey response,” the email to Peter Rowley stated. “We zealously guard the anonymity of responses, but if you would like us to locate your written comments and forward them to PENN athletic department we will attempt to do so upon receiving your permission.”

Rowley’s father reported that he granted permission for his comments to be shared with Penn Athletics, but that he still was never contacted by anyone from Penn Athletics. When asked for comment, the Josephson Institute responded that it was "not at liberty to discuss reports and related communications with our clients."

For Rowley, the lack of communication from Penn Athletics is hard to understand.

“People have reached out to the athletic department — players and parents — and nothing has happened. I don’t even know if they’ve ever even brought it up with [King],” Rowley said.

“If you have nine players quit in two years, how does that not raise a huge red flag?”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate

Most Read

SEPTA announces fare increase, service reduction in response to increasing financial challenges

Penn Medicine to take over two Crozer Health leases in $5 million deal amid system bankruptcy

Penn confirms five additional student visa revocations, bringing total to eight

More Like This